A name-dropper of a Cold War novel

Last Call for Blackford Oakes

A Novel

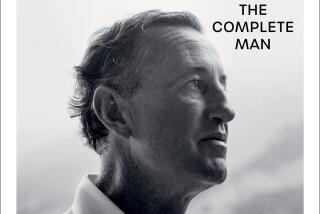

William F. Buckley Jr.

Harcourt: 354 pp., $25

*

About a quarter of the way through “Last Call for Blackford Oakes,” the 11th in William F. Buckley Jr.’s series of Cold War spy novels featuring the CIA’s answer to James Bond, is a love scene perhaps only Buckley could write:

“ ‘Do you hate Communism?’

“Blackford contracted his stomach, and then said it. ‘Yes.’

“ ‘I like the directness of your language.’

“ ‘Here is more directness. Will you marry me?’ ”

The year is 1987. The newly widowed Oakes, 60ish but still dashing, has been sent to Moscow to thwart a plot by die-hard Stalinists to assassinate Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev. Oakes is proposing to the 40ish but still beautiful Ursina Chadinov, who plans to deliver a rebellious speech at an impending East-West cultural summit. Her best friend happens to be the wife of Harold “Kim” Philby, the Cambridge-educated traitor who wormed his way into the highest levels of Britain’s intelligence services before defecting to the USSR in 1963.

Oakes’ offer to marry Chadinov, who bears his child, is significant. Buckley, longtime editor of the National Review and godfather of modern American conservatism, meant him to be an uncynical, non-womanizing anti-Bond: a Yalie, an Episcopalian, as sincere a romantic as he is a patriot. He has the good grace to feel bad about the collateral damage of realpolitik. The previous year, for example, President Ronald Reagan, believing Gorbachev to be an improvement over his predecessors, sent Oakes to derail an assassination plot by idealistic young Russians opposed to their country’s war in Afghanistan. This meant sacrificing the plotters, who were tortured or killed by the KGB.

In that effort, Oakes was aided by Gus Windels, a Ukrainian-born CIA agent half his age, who posed as his son and, for the childless Oakes, became much closer than a mere colleague. Now Oakes, disguised as Harry Doubleday, a publisher attending the cultural summit at the behest of the U.S. Information Agency, again works with Windels to protect Gorbachev, even though the Soviet leader is using the event to rally international opposition to Reagan’s “Star Wars” anti-missile program, which author Buckley clearly views as a master stroke in winning the Cold War.

That war is long over, but arguments about it go on -- in Buckley’s case, leavened with sly wit. Though Oakes is somewhat wooden as a character (hence his name?), Windels and Chadinov banter amusingly, and the cultural event gives Buckley a chance to zing some of his old literary and ideological adversaries: Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Carlos Fuentes, even Kris Kristofferson.

He bears a special animus toward novelist Graham Greene, who once worked under Philby at MI6, the British equivalent of the CIA, and continued to hobnob with him in Moscow. (Philby died in 1988, Greene in 1991.)

In “Last Call for Blackford Oakes,” the character’s love affair with someone connected -- however innocently -- to Philby leaves Oakes vulnerable. Philby finds a way to hurt him so terribly that he would commit suicide if his faith didn’t forbid it. A chance for revenge comes in 1988, when a Soviet scientist, a friend of Chadinov’s, tries to defect in Vienna. Philby is sent to prevent this.

Friends in high places -- Buckley’s main charm as a novelist, besides the wit, is his easy familiarity with the political and journalistic heavyweights he inserts into his fiction -- make sure Oates is on the U.S. negotiating team.

The history books say Philby died the same year in Moscow, safe from Western justice and unaware that the Soviet Union was about to implode. Without giving away the ending of “Last Call for Blackford Oates” -- an oddly perfunctory ending, as if the author suddenly ran out of gas -- let’s just say Philby doesn’t get off quite so lightly.

*

Michael Harris is a regular contributor to Book Review.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.