Scared silly

On a bright spring day at the Universal back lot, the world is coming to an end. Aliens have landed on the Eastern Seaboard; fear and destruction have been sown. Somewhere on the road from New Jersey to Massachusetts, a wet and surly mob has beset a father who’s managed to hotwire a van -- one of the last working vehicles on the road -- and dragged his teenage son onto the pavement. There are a hundred extras in soggy flannel, and lots of rain, and a giant crane that snakes about like a long-necked dinosaur.

Steven Spielberg, director of the newest version of H.G. Wells’ classic “War of the Worlds,” is ensconced at a video monitor, ignoring the tumult. His attention is focused solely on the frame in the eye of the camera. It’s a tight close-up of a hand rising out of the fray -- a hand bearing a gun.

There are hands, and then there are hands that can act. These five fingers happen to belong to Tom Cruise, who plays a onetime deadbeat dad, a dockworker now trying to save his 18-year-old son (Justin Chatwin) and 10-year-old daughter (Dakota Fanning).

On a blistering 72-day shoot that incorporates at least 10 major action sequences featuring everything from an overloaded river ferry to alien spaceships, the hand gets a lot of attention and a dozen takes. It must rise out of the chaos and shoot the gun, temporarily stunning the rampaging mob. It’s the endpoint of a camera swoop through the riot, a reminder of both the gun’s metaphoric power and its relative powerlessness in the face of more dominant alien intelligence and weapons.

Paranoia has always been the cultural oxygen feeding “War of the Worlds.” When Wells’ tale of alien invasion debuted in 1898, British-German hostilities were soaring, and German troops were massing just across the English Channel.

When Orson Welles’ famous radio play of the story filled the airwaves in 1938, Britain and France had just signed the Munich Pact, ceding Czechoslovakia to Hitler. Upon hearing Welles’ broadcast, more than a million naive Americans panicked, believing that Martians had actually attacked America. George Pal’s 1953 movie version arrived during the Cold War and won a special-effects Academy Award for its tinny evocation of aliens, with their flying saucers and their self-generated force field that could withstand an atom bomb.

Pal’s film foreshadowed the transformation of the alien-attack genre from realism to kitsch, movie versions of comic books, in which humans vanquish the marauders with superhuman feats of derring-do -- a la “Independence Day” or Tim Burton’s parody “Mars Attacks!,” in which yodeling causes the Martians’ heads to explode into gobs of green goo.

Spielberg’s version, which opens June 29 all across the globe, is one of the most hotly anticipated films of the summer, with audience awareness already running at blockbuster levels, according to Paramount. Like all the preceding versions of “War of the Worlds,” this one too will be a product of its time. Influenced by the fear that has infused the country since Sept. 11, Spielberg is bringing the story back to its dark Wells roots. He is returning to the author’s original stylistic impulse of hyperrealism, relaying only what an ordinary terrified man could discern from his own firsthand observations of the alien invaders. There’s a tendency among critics to divide the Spielberg oeuvre into serious fare and summer fare, but the man has experience with both kinds of films and wants to make the ultimate cathartic summer flick -- by infusing mass entertainment with the chill of reality.

IT’S ALL IN THE HAND

Throughout the rehearsal, the hand seems possessed by the Tom Cruise of the “Top Gun” era, certain, assured, as the superstar lifts it over and over again so it rises precisely into the middle of the frame. As the waiting camera crew prepares to start shooting, Cruise comes to confer with his director. For someone commanding a blitzkrieg $133-million production -- with the goal of scaring Americans out of their seats this summer -- Spielberg appears absolutely relaxed, even jolly, with a trademark baseball cap on his head and a cigar, apparently unlighted, in one hand. The actor is wet, like a baby seal in a battered leather jacket and sweats, but chipper. He and Spielberg take turns holding up the gun, practicing the shot.

“This is going to be so perfect you’re not going to know what to do,” says Cruise.

“What if you tilted it down like you were going into something?” asks Spielberg.

Cruise repositions it again, making his digits suddenly more prominent, and Spielberg seems pleased but wants more. He asks the actor to make his hands shake as he tries to lift the gun, and Cruise complies, testing out varying speeds of vibration. “I need someone to be struggling with Tom, fighting with him, holding onto him, but he has to be in position for the gun.”

When the filming finally starts, rain gushes down and mayhem breaks out on cue: The crowd attacks the van, with Fanning inside. A tense Cruise -- who’s standing outside the vehicle -- wrestles with an extra and fires the gun into the air to get the mob to stop.

After one take, Cruise jauntily returns to Spielberg, his hair now plastered onto his skull, a drenched cowlick streaked across the middle of his forehead.

“It looks like John Travolta in ‘Welcome Back, Kotter,’ ” says Spielberg, giggling. “I used to do that with my hair. Now I can just do illusions like that with my hair.”

The director’s still not happy with the gun. He takes it back in his hand, raising it again and again, trying to figure out what to do. “Why don’t you raise the gun a little slower?”

They begin to shoot rapid-fire takes of the hand, but Cruise no longer seems the stalwart icon of American manhood. His hand has been transformed into something primitive and raw, furious and grimly resolute, but only because there’s no other option than to be resolute. The hand quivers, desperate, afraid, and the black gun blasts.

A CRISIS FOR FOLKS LIKE US

It’s only during a brief lunch break outside his trailer that Spielberg seems ever so faintly tired, like an athlete catching his breath before running back into the fray. He barely eats. At 58, he’s as thin as he was in his wunderkind days, and he likes to shed weight when he directs because it increases his energy. He explains that when he first contemplated making “War of the Worlds” in the 1980s, he was thinking about doing it as a theme park ride. He even tried -- unsuccessfully -- to persuade Paramount to sell him the rights so he could make it part of the Universal Studios theme parks.

Yet as he wrote the scenario for the ride, “I got more and more invested in the possibility of a hyperrealistic version of an invasion of another world. The more I approached it from a realistic point of view and not a pop-culture point of view, the more excited I became.

“What if this really happened? What if it happened to people like you and me? Not to governments, not to presidents, not to generals, not to military personnel -- what if this really happened to the average American family? What would life be like in the six days it would take the ultra-superpower to realize their conquest of Earth?

“When I made ‘Private Ryan,’ I didn’t just want to make a war movie,” Spielberg says, drawing an analogy. “They’ve made a lot of war movies, and we all know what they look like and sound like. I wanted to get deeper into the point of view of what combat is really like from all the things I had been hearing and reading about for veterans of World War II, so I kind of put myself into that mind-set. Could I bring some of the tools I used to make ‘Private Ryan’ to tell a real story about an intergalactic invasion of the planet Earth?”

Wells’ book has often been seen as an attack on British colonialism, then spreading across Africa and Asia, where the white man’s might was as implacable and solipsistic as that of Wells’ devouring Martians. This version of the story is a far cry from the cuddly intergalactic utopianism that underlies Spielberg’s seminal hits from the ‘70s and ‘80s, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “E.T.” He’s made a 180-degree switch from the uplifting vision of mankind connecting with species from another planet. “Even though it goes against the grain of how I see the world, I’m more cynical in the new century than I was in the 1980s and ‘70s. It’s time for me to show the dark side of space.

“I think 9/11 reinformed everything I’m putting into ‘War of the Worlds 2005,’ ” he says. “Just how we come together, how this nation unites in every known way to survive a foreign invader and a frontal assault. We now know what it feels like to be terrorized.... And suddenly, for the first time since the Revolutionary War, certainly the first time since the Civil War, we know what it’s like to have our two front teeth knocked out, which is what happened when they took down both towers of the World Trade Center. And I think a lot of films, whether they intend to or not, are a reflection of our own paranoia and fear from what happened in 2001.”

Fear, he admits, has always been part of the wellspring of his own creativity.

Serial pursuit by an implacable force is a motif that runs through many Spielberg movies, from the shark in “Jaws” to the T. rex in “Jurassic Park” to the aliens in “War of the Worlds.” “It interests me how we deal with the forces bent on our destruction,” he says. “All the primitive nightmares that all of us share through the collective subconscious is the force that has created our imagination. I think fear is what creates people’s imagination. The imagination is fed by the worst-case scenario. Primitive man -- terrified of the moon, terrified of shooting meteors, frightened of the dark -- painted pictures of their world inside caves.

“If I wasn’t such a scaredy-cat I’d never have made ‘Duel’ or ‘Jaws’ or ‘Jurassic Park’ or ‘War of the Worlds’ or all of these movies I’ve made. People blame me for scaring them out of the water. I apologize for that. I’m only sharing what scares me.”

This said, fear, at least in Spielberg’s summer movie universe, can also be fun.

“When I make something scary, I get giddy. I can’t help myself, “ he says with a laugh. “I used to scare my sisters when I was a little kid growing up with them. I know how to do that.”

THROUGH FAMILIES’ EYES

In reconceiving Wells’ classic, ground zero for Spielberg was the image of a family, “which is the only image I can really, really, really talk about firsthand as a moviemaker. Start about what would a family be like as they react to something like that happening. To what they hear on television, what they hear on the radio, what they hear from their friends and eventually see with their own eyes. That’s when I got really excited. That’s what I brought to [screenwriter] David Koepp.”

He also had one other big piece of the puzzle -- Tom Cruise. Cruise had come to visit him on the set of “Catch Me if You Can” to discuss the marketing for their last film, “Minority Report.” They wanted to work together again, and in the back of a car, Spielberg pitched him three ideas: a love story, a western and “War of the Worlds.” “I just said the title, and he said, ‘That’s the one, that’s it. That’s our next project together. Go no further. Describe no more. Where do I sign?’ ”

“We did the pound,” attests Cruise, explaining that that’s when “You have the fists go together.... We were giggling and laughing. I called the studio. He called the studio.” In January 2004 they holed up for several days with writer-director Koepp, who’d written “Jurassic Park” and “The Lost World” for Spielberg, in a marathon brainstorming session.

“They’re highly enthusiastic. I tend to be more phlegmatic,” says the writer wryly. “They’re very energetic and have lots of ideas. There’s a lot of high-fiving.” Koepp ultimately had to say “enough” and go home and absorb it all.

The filmmaking team was also determined to stay away from cliches of aliens and to avoid anything that any director -- from George Lucas to Ridley Scott to Spielberg himself -- had done before.

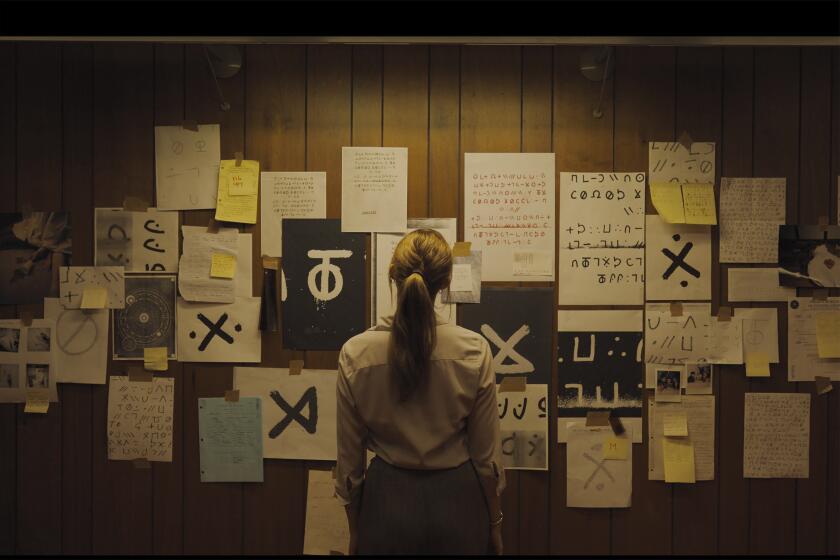

On the airplane to meet Spielberg for their first tete-a-tete on the film, Koepp had even drawn up a list of alien attack tropes that were never going to appear in this version of “War of the Worlds.”

“I’m sick and tired of watching New York get pummeled in movies and reality,” he says. “No scenes of beating up on New York. No destruction of famous landmarks. No shots of world capitals. No TV reporters saying what’s going on. No shots of generals with big sticks pushing battleships around the map. Let’s not see the war of the world. Let’s see this guy’s survival story.”

Jacking up the stakes for the characters, Koepp also wanted to “put the modern era out of business. Take away electricity, radio, television, automobiles (unless you mess with them), most modern weaponry. Every scene had to be about something very elemental, about shelter, or heat, seeking warmth, food. It’s the very simple things. That’s what a survival movie should be.”

Koepp, the father of two young sons, had been talking to Cruise about parenting. “Tom takes being a dad very seriously. So do I. So does Steven. That’s boring. Let’s talk about the times we failed hopelessly as a parent. I wanted to write a movie that’s about a bad father, who’s bitter, whose life had not gone where he wanted. What if the guy from ‘Top Gun’ had developed an alcohol problem and got thrown out of the military and spent the last 25 years feeling sorry for himself and ruining his personal relations? Let’s do that.”

Cruise laughs when he hears this characterization, one of those big Cruisian chuckles that fills a room. “I never thought of it that way. I just thought it would be a great character, and I’ve never played that. Here’s this mother. She drops [her kids] off for the weekend, and what happens? The world goes to pieces on his watch. He’s just not the guy you would want watching your kids when the world’s going to end. It’s not that he’s an evil bad guy, it’s just his level of awareness of responsibility. This guy’s a deadbeat dad. He’s a bigger kid than his kids are.”

Koepp turned in his first 80 pages in July, and Spielberg sent them at once to Cruise, who read them on his 42nd birthday and immediately called the director.

“He was actually screaming in the phone. I had to actually take the phone away from my ear, he was so excited,” says Spielberg. The director was in the middle of preparing his next film, about the 1972 Munich Olympics, and Cruise was supposed to begin the long-awaited “Mission: Impossible 3,” but director Joe Carnahan had quit. After the next 50 pages arrived in August, Cruise called up again. “He said, ‘If you move your Munich project, I’ll move “Mission 3.” ’ So we both decided to move our pictures back one movie, to do this immediately together.” It was to be the quickest start-up of Spielberg’s 33-year movie directing career.

Spielberg called producer Kathleen Kennedy, who was on vacation. Kennedy had produced a slew of pictures for Spielberg, among them “Jurassic Park,” but never this fast. “He said, ‘I’d like to shoot in November. Kath, don’t get freaked,’ ” Kennedy says. “Just think of it as a tight little drama, with three people in a family and thousands of people running around them. That totally put my mind at ease.” She laughs.

GEARING UP FOR THE BLITZ

SPIELBERG did try to prevent any producer, crew or studio heart attacks by previsualizing the film on the computer, a process in which he’d previously only dabbled. On smaller films, the director just arrives at the set in the morning and decides how to shoot. For “War of the Worlds,” he planned meticulously. He drew thumbnail sketches, which were rendered into storyboards. He then sat with electronic storyboard artists, who animated the sequences on the computer, using scanned-in shots of the real location and the actual camera lens that Spielberg planned to use.

Perhaps the toughest challenge in pre-production was figuring out what those aliens and their spaceships would actually look like. This is a subject that everyone involved in the production has been specifically banned from addressing, though Spielberg explains his thinking: No spaceships. No flying saucers. Nothing remotely resembling any machine or creature from the George Lucas universe.

“I wanted to go back to what Wells described in his book as tripods,” says the director. “What attacks us are huge 200-foot tripods. That, to me, is scarier than boomerangs with lights on the wingtips ... because they lord over us. They lord over our cities. They lord over our farms. They lord over our suburbs and shopping malls and schools and churches and synagogues, and they cast these giant shadows.”

He also sat with the designers from Industrial Light and Magic, who offered up a “rogue’s gallery of realistic life-forms that the audience would believe would really be coming down to do their dirty work.”

Yet what makes the aliens really scary comes right from Spielberg’s psyche, says “War of the Worlds” production designer Rick Carter. “He has a way of making them come alive by putting them through his own subconscious filter. He feels he has some inner understanding of what it is to be alien, just to be ‘other,’ like a dinosaur. [The aliens are] not just scary randomly or because they’re all-powerful. It’s because they take an interest in us. The shark in ‘Jaws’ or the T. rex in ‘Jurassic Park’ meets the aliens from ‘Close Encounters,’ and somewhere between the mixing they turn nasty.”

Many of Wells’ original ideas appear in the new “War of the Worlds,” albeit refracted and reinterpreted for modern times. Some of the book’s seemingly minor details now loom large, elements such as “the red weed,” says Spielberg. “The idea -- when we’re invaded, we’re not only invaded but the alien race is also sowing the seeds to terraform this planet to resemble the environment they’re accustomed to. When I read the book in college, I always was very interested in ‘What is all this red weed about?’

“Because Wells didn’t give us the alien point of view, I didn’t feel like I had to give the alien point of view either. In fact, it’s scarier to see them but not to know them. There’s lots of mystery to what they’re doing to our world.”

Screenwriter Koepp adds that much of Wells’ anticolonial fervor remains -- if you just look beneath the summer-movie facade.

“The local insurgency always kills you,” Koepp says. “That’s why global adventures never work, and it has obvious parallels to the way we conduct our foreign policy. I view it as an antiwar film, especially an anti-Iraq War film. You don’t foreground it because it ruins the movie. If someone wants to see it, great. If they don’t, they can just watch the movie and be happy.”

Koepp stresses that he’s speaking for himself, not the whole filmmaking team.

Demurs Spielberg with a chuckle, “I’m just trying to scare a lot of people all on the same weekend.”

INSTINCTS IN SYNC

“Riot, riot,” yells the assistant director, and the crowd begins to surge toward Cruise and the car.

“Don’t make me get Charlton Heston to do this,” jokes Spielberg to his lead actor.

Cruise, gun in tow, spins around in the center of the teeming mass, centrifugally creating a space for himself.

“Tell Dakota to stick her head out [of the van],” says the director, examining the monitor, then proceeding to pick out extras he wants moved out of the frame because their clothing is too bright.

As the camera crew sets the lighting, Fanning returns to wait by the director. She’s a moppet in a pink flowered shirt, miniskirt and boots, and a crazy, striped-sleeved sweater. The part was written with her in mind, and Spielberg says (when she’s not around), “She’s a genius. She is somewhat of a savant, like those kids who know how to play the piano, like Beethoven at 4 years old. I’ve never worked with anyone like her before at that age, at 10.”

On the set, the mood remains jocular and light. Visitors come -- Cruise’s nephews, and the writer-director J.J. Abrams, who comes every day to confer with the actor about the upcoming “Mission: Impossible 3.”

A basket of chocolate bunnies gets passed around, and Spielberg tells people -- mostly Fanning -- how when he made “Jaws” he recommended to the Universal marketing staff that they sell chocolate sharks full of cherry juice that would squirt out when you bit down. “They stared at me, and someone at the end of the room changed the subject.”

“Maybe for the 30th anniversary of ‘Jaws,’ it could be white chocolate with cherry inside,” he muses.

Fanning looks at him weakly, not knowing what to say.

“That’s the same reaction I got in 1974,” he teases.

Justin Chatwin, playing Cruise’s son, arrives to show Spielberg the gash on his neck. “It should be streaming down his neck,” Spielberg tells the makeup artist. “More PG-13 than PG, but no R.”

As shooting begins on the sequence, Cruise tries variations, from actually spinning around with the gun, to staggering about uncertainly, to frantic whirling. “Where’s my son?” he screams to the crowd, and when he spies Chatwin lying on the ground, he drags the teenager toward him. The team is firing off takes fast now, because Fanning, who can work only limited hours, will soon have to go. Spielberg is calling for lens changes, 50 millimeter, 65 millimeter, and meticulously excising extras and anything that might distract the eye from Cruise.

When Cruise finally emerges during a camera break, the director jokes, “I sped it up for you. That was the Steven Spielberg speed take.” Spielberg wants to adjust Cruise’s lines and asks him to call for his son by name, a slight tweak that nonetheless personalizes his character’s torment. As they shift in for Cruise’s close-up, it’s as if the actor’s adrenaline flows to the surface of his face, the weary terror and stress etched just a little more fiercely.

“Great, great,” says Spielberg, “great intensity.”

Later, Cruise explains that when they’re actually shooting, the pair are often past the point of discussion. When Cruise is filming, he often doesn’t sleep much, sometimes as little as one or two hours a night, he says. He likes to arrive early on the set. “Sometimes we [he and Spielberg] sit there and we walk the set together. Even us talking about another subject, we’re always thinking about the movie. There’s a connection and a synchronicity that finds its way into the work. To someone outside, it looks like we’re not even thinking about it, but you’re always thinking about it. It just lives there.”

Spielberg concurs. As the duo -- certainly two of the most commercially potent figures in Hollywood history -- contemplate an alien takeover of planet Earth, they’re not overanalyzing. They’re letting their instincts do the talking. “We live by the hairs on our skin,” says Spielberg. “When they stand up after hearing an idea ... we’re going with that idea.”

*

Contact Rachel Abramowitz at Calendar.letters@latimes.com.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.