No more wacky thrillseekers

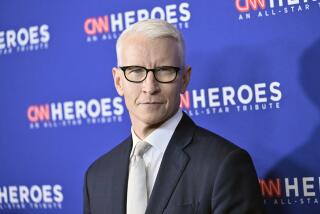

The macho postures were predictable and they were instantly mocked. Here was CNN’s Anderson Cooper, the hood of his red jacket whipping around his head in the high winds of Hurricane Katrina as he struggled to narrate the weather. And there was Fox’s Steve Harrigan, blown nearly out of the camera frame, exclaiming, “Oh man, I think this wind can knock me down!” (“We’re not asking you to take one for the team here, Steve,” the anchor replied dryly, off camera.)

New York Daily News TV critic David Bianculli was underwhelmed. “TV reporters unpacked their brightly colored slickers and left their common sense at home,” he wrote Tuesday, “in hopes of riding the next big media weather wave.”

Critic Jill Vejnoska at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution poked fun at reporters’ raingear, covered in network logos. “What’ll they call the next one, Hurricane Dior?”

They may have mocked too soon.

Those early images have been replaced by ominous ones -- images of reporters on the dangerous front lines of a complete breakdown of civilized society. Great work by real reporters -- brave reporters -- bringing back simple news about the living and the dead.

“It defies comprehension that the United States can look like this,” CNN correspondent Jeanne Meserve said on the air Wednesday. And on Thursday morning, CNN’s Chris Lawrence reported an absolutely chilling scene from the New Orleans convention center: “We saw dead bodies. People are dying at the convention center, and there’s no one to come get them.... Right in front of us as we were watching this, a man went into a seizure on the ground. It looked like he was dying. People tried to prop his head up. No one has medical training. No ambulance can come. There’s nowhere to evacuate him to. It is just heartbreaking that these people have been sitting there, without food, without water.... And they keep asking us, ‘When are the buses coming? When are the buses coming?’ ”

Like the windblown roof of the Superdome, the mainstream media’s reputation has been in tatters (due to scandal, circulation and ratings woes and competition from the Internet), and the often superb coverage of the 2001 terrorist attacks has faded from public memory. Hurricane Katrina has starkly displayed the press at its best. Reporters, most of whom have been working in a kind of communications blackout, have left the showboating behind (if standing in the wind to demonstrate its ferocity can be called showboating) and are performing the most basic tasks of journalism: tell what you know, describe what you see, share the human drama unfolding before you.

“People sometimes think we’re a bunch of wacky thrill seekers,” CNN’s Aaron Brown concluded Tuesday night after a powerful interview out of New Orleans with Meserve, who normally covers homeland security. “And no one who has listened to the words you’ve spoken or the tone of your voice could possibly think that now.”

“We are sometimes wacky thrill seekers,” replied Meserve. “But when you stand in the dark, and you hear people yelling for help and no one can get to them, it’s a totally different experience.” It was this interview with a shaken Meserve that served as a kind of turning point for the coverage. Before her report, in which she drew a horrifying verbal portrait of a city on the verge of a compounding catastrophe, the Katrina story seemed to be “New Orleans dodged a bullet,” since the storm had veered away from the city. “It was the moment for viewers and in some respects for me that we understood it was not getting better, it was getting worse,” Brown said.

The man who practically invented what would later become the oft-parodied, wind-blown-reporter approach to hurricane coverage has been watching Katrina almost constantly since Sunday, safe in his dry New York digs. A wistful Dan Rather answered the phone with a little joke: “I used to be Dan Rather. I used to cover hurricanes.” Indeed he did. He is the prototype of the TV reporter whose career was made in a storm. During 1961’s Hurricane Carla in Texas, he even tried to chain himself to a tree but gave up when he realized the storm would hit at night and he wouldn’t have enough light for the shot. CBS executives, impressed by what they had seen, brought him to the network.

“The reporting for Katrina has been fabulous, among the best I have seen, right across the board,” Rather said. “Television is at its best when it commits itself to public service and this was a classic, almost pluperfect, example of television news as a public service.”

Rather’s greatest contribution to hurricane coverage was his insistence that the radar image of Hurricane Carla be broadcast superimposed over a map of the region. That dramatic image -- Carla was an immense storm -- helped persuade half a million people (many of whom had become blase about hurricanes) to evacuate.

“It was a breakthrough,” he said. “People began to evacuate, and at the time it was the largest peacetime evacuation in the country.... And please do not read this as braggadocio, almost from the moment we put that up, people began to flee. As a result, when Carla came in ... the death toll was very small.” (There were 46 deaths.)

“By and large,” he added, “the reporting on hurricanes is the most responsible reporting done on television. You can say that’s damning with faint praise, but there it is. Covering a hurricane well is a dangerous line of work, and it’s very easy to overlook this.”

This week, television viewers saw reporters who were not only telling a difficult story under difficult conditions, but saw the raw emotion that reporters simply could not hide. Whether this is a breach in the professional mode is debatable. But it made for some very powerful television. “I have been incredibly impressed by the humanity of the coverage,” Brown said.

On a tape broadcast by CNN, a local reporter, unidentified, was in tears as she interviewed a man named Harold Jackson, whose wife had slipped out of his hands into the floodwaters. “You can’t find your wife?” she asked, her voice rising in pain. “What’s your wife’s name in case we can put this out there?” Reporters talked about giving drinking water and rides to people in dire straits. They lent victims their satellite phones so they could call worried relatives. National reporters used national airwaves to allow people to ask after missing loved ones. And at least one television station employee, Chris Merrifield of WWL-TV in New Orleans, was shown rescuing a motorist trapped in floodwaters by pulling him out his car window.

“There are elements to the story that, if handled well, can help improve the way the public perceives the press,” said Tom Rosenstiel, director of the Project for Excellence in Journalism in Washington. “The other thing is that the press is doing a bunch of things that are new. They are reading e-mails, saying, ‘I am looking for my nephew ... so-and-so, if you can hear me, please call.’ That’s community journalism on a national scale and I think that will go a long way to demonstrate that the press is doing more than just thrill seeking.”

But, cautioned Rosenstiel, “the idea that this could rehabilitate TV is an oversimplification.... While the story has advantages for television, it also exposes grave weaknesses.” The first days after a catastrophic event like a hurricane or the 2001 terrorist attacks put television at an advantage, but the limits of the coverage lead to a “bias of perspective,” as Rosenstiel put it. “It’s a little bit like the embedded reporters in Iraq. Any one reporter is not sufficient; you need all the reporters to come together and that information needs to be synthesized. The continuous loop quality, particularly of cable, is very frustrating.” And then, he said, there is the potential for dissonance when words don’t match pictures -- when, for instance, a live conversation with a doctor about the potential for disease outbreaks takes place over video of looting.

Although the immediate aftermath of a catastrophe such as this one belong to television -- it’s hard for newspapers to compete with the immediacy of all that video, not to mention those dramatic early shots of TV folks blowin’ in the wind -- all reporters are facing the same hurdles, working in the same awful conditions as the victims themselves. And there will come a point -- in this swelling tragedy, it’s hard to predict when -- that the print folks will begin to dominate, on stories about delivery of services, how the government performed, how the money was spent, logistics, the economy and politics.

Carroll Doherty, associate director of the Pew Research Center for People and the Press in Washington, said his organization will conduct a survey next week to gauge the public view of the media’s Katrina coverage. “For what it’s worth historically, 9/11 was the news media’s last great moment in terms of the public view. I’d be hesitant to say much more than that because we don’t know how the public is reacting to this crisis -- whether there will be the same sense of unity and common cause. There was an immediate rally effect shortly after 9/11, and that rubbed off on the media.”

By November 2001, said Doherty, the increase in favorable attitudes toward the media on all measures was “stunning.” Six months later, however, levels of esteem had dropped back to normal; low, in other words.

Judy Muller, a veteran network news correspondent and USC journalism professor, has noticed that most hurricane survivors seem to be welcoming the intrusions of reporters. “Usually in disasters, people don’t want to talk,” she said, “but in this case, they are using us as a community bulletin board. It’s helping people connect in a very real way.” (With the notable exception of a live exchange between Fox News Channel’s Shepard Smith and an unnamed man in New Orleans just before Katrina hit: “Why are you still here?” asked Smith. “None of your ... business,” the man replied.)

The really good news for the media is that Hurricane Katrina is not ideological and has no partisan underpinnings, at least for now, Rosenstiel said. Nor can anyone accuse the media of sensationalizing what is clearly a disaster of historic proportions.

“I hope that this is a story that reminds people that it ain’t all about Aruba and Jayson Blair,” said Brown, referring to what many have criticized as saturation coverage of a missing Alabama woman, Natalee Holloway, and the scandal that rocked the New York Times in 2003. “Most of the time, most of us really want to do serious work.” And, he added, referring to a spike in ratings this week, “It’s damn good for us to be reminded that viewers will come to us when we present important stories well.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.