Antelope Valley Is Upscale Bound

Check out this model home: It’s got five bedrooms, gorgeous slate tile on the floors, marble in the bathrooms and a bonus loft with enough space to put flat-screen TVs on adjoining walls so as not to miss a single ballgame.

Five years ago, developer Capital Pacific Homes was selling similarly outfitted homes in the upscale Orange County suburb of Laguna Niguel for $2.2 million.

But here in the arid, recently plowed high desert in west Lancaster, where Joshua trees sprout in wild clusters across from rows of new houses, they’re going for about $500,000.

Scott Coleman, a 33-year-old actor from Culver City, bought one. So did Mark Snaer, 27, a recently trained air traffic controller from San Diego. So did Monica Carreon, 26, a stay-at-home mother from Long Beach whose husband is a welder.

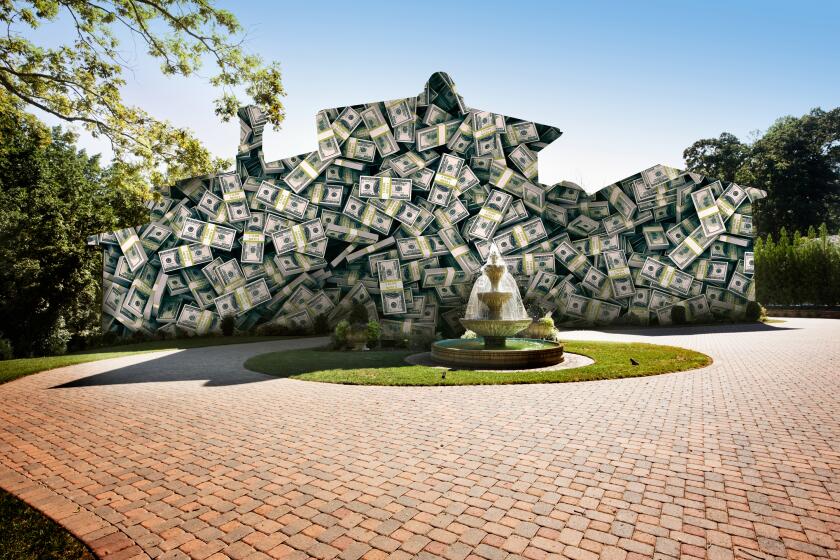

The Antelope Valley has long been a magnet for development, but these days, the boom is accelerating and going upscale.

Lancaster, the fastest-growing city in Los Angeles County, saw its assessed property values increase about 29% last year, according to a report released last week by the county. And its neighbor to the south -- Palmdale, the second-fastest growing city -- was not far behind.

By comparison, property values in the city and the county of Los Angeles increased 11%.

“Nowhere else in L.A. County has been like that,” County Assessor Rick Auerbach said. “And the reason is that there is land to build on.”

There’s so much land that developers offer middle-class and even working-class buyers huge homes on lots that in other areas would be used only for multimillion-dollar houses.

And though some parts of Southern California are beginning to show signs that the housing boom is stalling, planners say the expanse of raw land in the Antelope Valley means growth will continue.

The Southern California Assn. of Governments projects that the Antelope Valley’s population will rise from about 290,000 to nearly 500,000 in the next 15 to 20 years. Several planned communities are also slated to the west and south, adding more than 100,000 residents.

But amid the rising home values and booming growth, the Antelope Valley also shows signs of strain.

Even with the influx of middle-class residents, parts of the valley remain poor. In Lancaster, violent crime has dropped in recent years but property crime is up. Law enforcement officials said they are dealing with gang activity that they say has come to the valley as residents move in from urban parts of Los Angeles.

The school district is struggling to handle the growth.

“Economically, it’s outstanding. Educationally, we’re dying,” said Larry Freise, coordinator of consolidated projects for the Antelope Valley Union High School District.

The region’s high schools house twice as many students as they were built to hold, and voters last month turned down a proposed bond issue that would have paid for a new school, forcing students to remain in “the cheapest portable that there is” until a new campus can be financed and built, Freise said.

Nickie Perez, a 19-year-old who moved to the high desert as a child, said growth has brought smog and crime to what was once a pristine community.

“I remember looking out over the mountains here,” she said, “and it was so pretty, so clear and crisp. Now the pollution is here. I think it’s from the population increase and traffic.”

Perez, who lives in west Lancaster, said she no longer feels comfortable going out alone after dark and doesn’t jog without a whistle or pepper spray to ward off possible assailants.

The growth, Lancaster Mayor Bishop Henry Hearns said, “is both good and bad.”

“It means people are coming, and people is what we’re all about,” Hearns said. “But at the same time, what we really want is not just growth but controlled growth. We want to make sure we put people in the right places and have the amenities to take care of them.”

The drawbacks aren’t stopping new residents dazzled by the prospect of a big house with a reasonable mortgage.

Michelle Stall and her husband traded up to Capital Pacific’s Clifton development, buying a two-story, 3,200-square-foot home in west Lancaster after selling their three-bedroom ranch house in Lake Los Angeles to a couple from Highland Park.

Stall, a real estate agent in the area, said her daughter also bought a home in Lancaster and that her mother was considering moving out from Glendale.

Along with the new residents come new amenities: A hospital is being built in Palmdale, and specialty retailers including Trader Joe’s and Panera Bread have set up shop. A Wickes Furniture store took the place of a shuttered Kmart.

There are so many people furnishing and decorating houses here that Hal Newman, a fast-talking art salesman, goes up and down the pristine streets knocking on doors to hawk framed prints.

He bounds into the Clifton sales office bearing a framed reproduction of a Picasso.

“This is gorgeous stuff,” he tells Coleman, who has stopped by for a cup of coffee. “We’re doing cash, we’re doing check and we’re doing credit card.”

The sense of hope and excitement among the new-home buyers is palpable. Several have Newman’s paintings on their walls. Coleman is buying two flat-screen TVs for his den; another man put one in his bathroom.

Some homeowners who have staked their futures on the high-end houses on the city’s western edge say they were careful to pick a subdivision where the homes were sold to families rather than investors.

At Clifton, sales managers Steve and Patrice Weston screen out buyers who don’t plan to live in the homes themselves.

Rick Hernandez, the company’s vice president for sales and marketing, said the developer, which gave up building in coastal areas because of the lack of land, has decided to make a similar effort throughout its Antelope Valley projects.

The biggest challenge, said Danny Roberts, economic development director for Palmdale, is to bring more jobs to the region.

About 65,000 of the region’s residents commute to jobs in other parts of the county -- slightly more than half of the working adults.

Residents say their commute to Los Angeles can take 90 minutes or more one way -- and that’s without an accident that jams freeways. A SCAG study found that the average rush-hour crawl at the key Interstate 5/California 14 junction would slow to 11 mph by 2020. Transit officials say they desperately need money to widen numerous rural, two-lane roads that fill with commuters.

Palmdale has also put money into amenities designed to make living in the community more comfortable, adding a water park and an outdoor amphitheater where the city sponsors a free concert series.

“We’ve made plans for our quality of life,” Roberts said. “So if people come here, it feels like home.”

Stephen Cross, 35, recently moved with his wife and child to the Clifton development from Culver City. But Cross kept his job as a personnel analyst for the Los Angeles Department of Housing and takes an express bus back and forth.

He said they pay less for their five-bedroom house than for the condo they rented in Culver City. And, he said, his commute is less stressful than it was before -- because he doesn’t have to drive.

At the end of a recent workday at 5:15 p.m., Cross blew out of his West 7th Street office building downtown, five minutes late for the bus.

“Oh, no,” he groused spotting it across the street. “She just turned the corner.”

The “walk” sign flashed and Cross flew through the Figueroa Street crosswalk, rounding the corner as the bus pulled up.

In 15 minutes, as the bus pulled onto the Golden State Freeway, all chatter stopped. Seats reclined.

Cross pulled his shades over his eyes, leaned his head back and folded his hands at the tip of his blue tie. In minutes, his hands unclasped and fell to his legs. His head tilted. A soft snore escaped his open mouth.

As the bus neared the Palmdale station, Cross woke up. He had time to check his cellphone before his stop at Lancaster City Park. His wife, Roxanne, has called, wondering when he would be home for dinner.

By the time Cross walked in at 7:30 p.m., his wife had already eaten. His 1-year-old son, Stephen Jr., squealed.

Cross chased him around the house as he loosened his tie, shaking off the two-hour, 15-minute commute (he had gotten up at 4:30 a.m. to prepare for work).

Later, he and “Boo-Boo,” as the boy is called, will have dinner together. Cross hurriedly consumed his steak burrito. The sun was setting, and he did not want to waste the sweetest part of the day: their evening walk.

“This is when we talk and dream,” Cross said.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Land rush

Lancaster and Palmdale continue to experience rapid growth in population and property values. Several nearby developments will create whole new communities where there is now open space.

1) Centennial - 23,000 homes

2) Newhall Ranch - 20,885 homes

3) Las Lomas - 5,800 homes

4) Ritter Ranch - 7,200 homes

5) Anaverde - 5,200 homes

*

Population increases expected for north Los Angeles County:

Lancaster

2005 population: 142,000

2020 projected population: 215,000

*

Palmdale

2005 population: 146,000

2020 projected population: 260,000

*

Santa Clarita

2005 population: 170,000

2020 projected population: 211,000

*

Unincorporated areas

2005 population: 157,000

2020 projected population: 281,000

*

Los Angeles County cities with the largest percentage increase in assessed value, 2005-2006:

*--* 2006 Percent value* City change (billions) Lancaster 29.2% $9.7 Palmdale 21.1 10.3 Azusa 17.7 3.0 Signal Hill 15.2 1.8 Malibu 14.3 8.5 West Hollywood 14.3 6.0

*--*

*--* 2006 Percent value* City change (billions) Pomona 13.9 8.1 Inglewood 13.4 6.1 Calabasas 13.4 5.5 La Puente 12.9 1.6 County total 10.8 921.6

*--*

* Revenue-producing valuations: Excludes properties exempt from property tax, except $8 billion of homeowners’ exemptions that are reimbursed by the state.

*

Sources: ESRI, Southern California Assn. of Governments,ELos Angeles County assessor, Times reports

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.