Who’s really locked up in Guantanamo?

BY NOW, just about every American ally in the world has said the United States should close its detention camp at Guantanamo Bay. God forbid, responds President Bush, for the camp holds terrorists caught on the battlefield fighting the U.S. and who would kill again the moment they are released.

Yet it’s an open secret that the administration itself is trying to make Guantanamo go away by releasing some prisoners and shipping the rest to other countries. What the administration has resisted with real fury are not the calls to close the camp but those to open it -- through the release of information and the scrutiny of courts.

The reason may be that the more that is learned about these prisoners, the more holes appear in the president’s narrative of a tough and triumphant fight against Al Qaeda. Instead, when the full story is told, Guantanamo may come to stand as much for incompetence as it does for injustice.

Last week, under court order, the Pentagon released the transcripts of several hundred hearings held to decide whether Guantanamo prisoners were in fact “enemy combatants.” Classified evidence was deleted, but what emerges is how insignificant most of these prisoners are. Fewer than half were caught on battlefields in Afghanistan or by U.S. troops. A majority were turned over by Pakistan (often for cash bounties). Few “combatants” are even accused of having fought. Many are held simply because they were living in a house associated with the Taliban or working for a charity linked to the group.

It seems that U.S. forces, inundated by thousands of captives after the Afghan war, didn’t have enough experienced interrogators and interpreters to sort out the actual terrorists from Arabs unaffiliated with Al Qaeda. But they were under pressure to get results and unwilling to believe that their Pakistani allies could deceive them. Prisoners who claimed to know nothing were subjected to increasingly brutal treatment until some confessed or accused others.

According to Pentagon documents, Mohammed Al-Qahtani, the alleged 20th 9/11 hijacker, accused 30 fellow prisoners of being Osama bin Laden’s bodyguards -- after Qahtani was tormented by weeks of sleep deprivation, isolation and sexual humiliation. That the Pentagon finds confessions obtained this way credible is, well, incredible. How many false leads has it chased, and how much lifesaving intelligence has been lost?

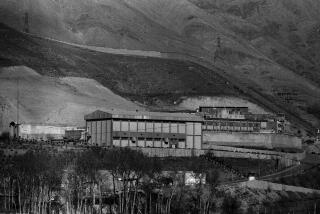

What the administration doesn’t want to face is that, as the small fish were taken to Cuba, Pakistan arranged escape routes from Afghanistan for more dangerous jihadists -- presumably those with cash or connections to Pakistani intelligence services -- including several hundred flown out of the city of Kunduz before it fell to U.S. forces. The Pakistani military maintains close links with Al Qaeda-linked militant groups created to wage war in Kashmir and Afghanistan, and the Taliban continues to hold sway over Pakistan’s tribal areas on the Afghan border. Bush should devote the resources needed to stabilize Afghanistan and tell Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf to end, finally, the military-Islamist alliance that has made his country the new home base for Al Qaeda and the Taliban.

In the meantime, here’s the score: the U.S. got Guantanamo, the Pakistanis got paid and Al Qaeda and the Taliban mostly got away. Michael Scheuer, the former head of the CIA’s Bin Laden unit, recently told the National Journal that less than 10% of Guantanamo prisoners are high-value Al Qaeda operatives with any knowledge of terrorism. Of those turned over by Pakistan, he said: “We absolutely got the wrong people.”

That doesn’t mean the camp’s prisoners are all innocent farmers. Even if they weren’t fighting the U.S., many went to Afghanistan to help the Taliban build its “pure” Islamic state -- precisely the kind of men Al Qaeda tries to recruit as cannon fodder. Some could become killers if released. But does that make them different from hundreds of thousands of other angry young men throughout the Muslim world who believe in the same cause? There is no shortage of potential suicide bombers. Guantanamo does nothing to solve that problem. It probably makes it worse.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.