Injected Cells Cure Tumors in Mice

- Share via

White blood cells from mice that are naturally immune to cancer cured tumors in other mice and provided them with lifelong immunity to the disease, researchers reported Monday.

The finding indicates the existence of a biological pathway previously unsuspected in any species. A small team of researchers is working to understand the genetic and immunological basis of the surprising phenomenon.

Preliminary studies hint at the existence of a similar resistance in humans. Researchers hope that harnessing the biological process could lead to a new approach to treating cancer.

“The idea of cells being able to kill tumor cells ... is very exciting,” said biologist Howard Young of the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Cancer Research in Frederick, Md. “But this is a mouse, and there is no guarantee that the same gene will exist in people.”

The findings have not been replicated in any other laboratory, primarily because the researchers who discovered the cancer-immune mice have only recently bred enough to supply them to other scientists.

“Our initial ability to collaborate was very limited by the number of mice that were actually available,” said Dr. Mark C. Willingham of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, a coauthor of the paper.

But Dr. Zhen Cui of Wake Forest, whose team published the findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, said he expected rapid replication of the results because the findings were so clear-cut and easily observed.

“This is a truly remarkable phenomenon ... and it really needs confirmation from other institutions,” he said.

Cui and his colleagues stumbled on the immune mice by accident in 1999. They were injecting mice with a highly virulent form of cancer cells as part of an ongoing study of the biological mechanisms that cause cancer to spread.

On April 13 of that year, a graduate student told Cui that one of the mice she had injected did not develop a tumor. Assuming the student had simply overlooked the mouse, he told her to do it again. And again.

After a total of five injections -- the last equal to 10% of the animal’s body weight -- the mouse remained free of tumors.

Intrigued, they bred the mouse and found that about half its offspring had the same resistance. The trait bred true through subsequent generations and the team eventually had a colony of about 700 resistant mice. Cross-breeding the mice with other strains transferred the resistance to them as well.

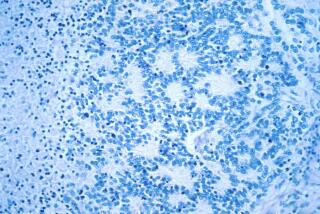

When cancer cells are injected into the mice, their white blood cells surround the tumor cells and rupture them in a process called cytolysis. The same killing process occurs when tumor cells are formed naturally by the action of carcinogens.

As the animals get older, injected cells might form a tumor, but the cancer is cleared in a day or two. The animals live a normal lifespan, about two years.

In the new study, the team took white blood cells from the immune mice -- a combination of natural killer cells, macrophages and neutrophils -- and injected them into mice already carrying a variety of tumors, some of which were extremely aggressive. In every case, the cancers were destroyed, even if the cells were injected at a point distant from the tumor. Healthy tissues were not affected.

The mice that received the cells, furthermore, were protected from new tumors for the rest of their lives. The researchers have no idea how the immunity continues.

“This is the first report of a novel [treatment] mechanism,” said Dr. Andrew Raubitschek, a cancer immunologist at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte. “The two most dramatic things are: one, that the response itself is outstanding, and two, the fact that they looked at a variety of different cell lines and found the activity was there for all of them.”

The fact that the immunity can be transferred between mice indicates that the phenomenon is more than a simple aberration in one strain of mice and gives hope that such manipulations can lead to a therapy for humans.

“This deserves intensive follow-up,” said Dr. Richard Miller of the University of Michigan Medical School. Cui’s papers “are technically sound, carefully controlled and well thought out. But whenever there is a result this surprising, it’s always important to have others confirm it.”

Cui and his colleagues believe that the resistance results from a mutation in a single gene and are attempting to find it, but that has proved frustrating. The primary problem is that while the gene mutation may be in one location in one family of mice, it may occur on a different chromosome in another family.

“That’s quite surprising to us, and we are still trying to pin it down,” Cui said.

The Cancer Research Institute in New York City, which is the primary sponsor of Cui’s research, has brokered a collaboration with Dr. Bruce Beutler at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla and immunologist Robert D. Schreiber of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis to try to identify the gene.

The big question is whether Cui’s discovery could ultimately lead to human treatments.

Preliminary tests hint at the possibility.

Cui’s team developed a test-tube assay to determine whether mice were immune without injecting them with tumor cells. In the test, white blood cells from the animal are mixed with tumor cells. If the animal is immune, the white cells surround the tumor cells in a characteristic rosette pattern.

Cui said the team had tested cells from humans in the same fashion and had observed the same phenomenon.

“Some people never get cancer,” said Young of the National Cancer Institute. “That may mean they have an active gene and are inherently more resistant to cancer. That is not at all inconceivable.”

The approach used in mice would most likely not be applicable in humans, Willingham said. The need to match cell types to avoid rejection would make using living cells extremely difficult, and there would also be the issue of viruses and other potential contaminants.

But if scientists can understand the mechanism, he added, they can manipulate it with drugs to spark a similar immune response in the patient’s own cells.

Despite the obvious promise of the approach, Young urged caution.

“People have been killing tumors in mice for 30 years, and only some of those techniques have led to human therapy.... Because they don’t know anything about the gene yet, the application to human therapy remains a big question mark.”