A clouded life finds some light at Rainbow

Alexander Riddick, a bearded 55-year-old in a Steelers cap and purple sports coat, says he isn’t going to lie to me. He loved that wife of his, Ethel Mae, but they had an agreement. He was eager to hit the road every now and then over the course of 30-plus years, and conveniently enough, she never seemed to mind getting him out of the house.

Riddick would bum his way to Vegas, or bus home to Virginia, usually up to no good as he drifted. Each time, once he’d gotten over the scent of another woman’s perfume, he’d come around to how much he needed the woman he didn’t deserve.

Back he’d crawl, scratching at the door, and she’d let him in.

Even with all that forgiveness, Riddick didn’t have any idea how much he loved his wife until two years ago, when a massive heart attack took her quickly, sweeping in like an unexpected gust.

“I woke up and realized I was alone,” Riddick says of those first days without her. “And you know what? She had said, ‘Danny’ -- she called me by my nickname -- ‘you gonna miss me when I’m gone.’ ”

Riddick was living with her in Covina when she died, but her name was on the lease, not his. And he was a bad risk, with no steady job and a rap sheet that included a few trips up the river on drug convictions.

So he knocked on the doors of relatives in Los Angeles, rattled around a bit and ended up falling apart on skid row in downtown Los Angeles. Riddick got into fights, stayed up all night to keep from being robbed, got locked up for unpaid jaywalking tickets, blacked out a couple of times and was rushed to the hospital once by paramedics.

Skid row is full of stories like his, troubled souls who never quite pull themselves together, despite the huge cost to taxpayers for everything from police patrols to prison cells. But Riddick caught a break when he stopped by Lamp, which treats people with chronic mental illness.

Stuart Robinson, a Lamp director, says Riddick was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, a condition with characteristics of schizophrenia and a mood disorder. Robinson said it’s likely Riddick has had the condition for many years without knowing it.

When Riddick wasn’t at Lamp, he shined shoes outside downtown restaurants and hotels, blew the money on rock cocaine and swore he could hear dead relatives telling him what a failure he was. He slept on sidewalks but kept returning to Lamp, where Robinson, who has a gift for connecting with everyone who walks in the door, knew he was looking at a man he could help.

“He’s a prime example,” Robinson said, of someone who could benefit from what’s known as permanent supportive housing. That’s a setup in which all the services a client might need -- drug rehab, mental health services, job counseling, life-management workshops -- are just down the hall from his apartment.

That doesn’t always happen quickly, though. Lamp lets its clients come around to the idea of helping themselves, because pushing too hard might drive them away for good. In Riddick’s case, the transformation dragged on for months.

Earlier this year, when Riddick was finally ready, he ran up against a severe shortage of supportive housing. Robinson, though, had his eye on a new facility under construction just around the corner on San Pedro Street. On Oct. 17, as the last nails were being hammered, he walked up to Riddick at Lamp and handed him a set of keys.

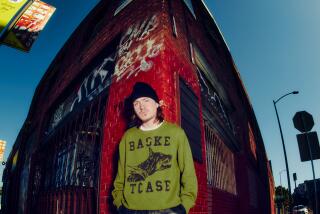

On Tuesday morning, I visited his new digs. Rainbow Apartments is an 89-room, hotel-like building with a sleek, minimalist design. He checked me in at the counter, pushed the elevator button and escorted me up to his apartment.

“This is home,” he said proudly.

It’s a nice, clean space, with a 12-step book next to his bed and two pairs of shoes on the floor under a window. Not much of a view, he says, but that’s OK.

“I need to stay focused.”

To show me he means business, he went over to his nightstand and pulled out a daily calendar. Written in for Saturday at 12:30 p.m. is a shoeshine job in Little Tokyo, where he met a woman with nice boots and offered to shine them like new. Come by every Saturday, she told him.

On Sunday at 9 p.m., he’s got a shoeshine appointment with the security guard who works at Pete’s Cafe and Bar at 4th and Main streets.

That calendar is going to be filled, Riddick said, with shoeshine jobs and the times of all his appointments for rehab and counseling. For today, he wrote in a reminder to pay the rent with his disability check.

“I got to organize my life.”

Casey Horan, Robinson’s boss at Lamp, insists this model is the answer to the much-debated policy disaster known as skid row.

“This is big news,” she said of Rainbow Apartments, which was built and will be managed by the Skid Row Housing Trust. “We have maybe 4,000 permanent supportive housing units in all of Los Angeles County, and close to 37,000 chronically homeless people with severe mental illness.”

Closing that gap is the key to getting people off the streets in skid row and elsewhere, says Horan. Mike Alvidrez, who runs the Skid Row Housing Trust, says 300 people applied for the 89 units at Rainbow.

The good news, he said, is that another Rainbow-type building will be erected on the vacant lot next door, financed, as well, with local, county, state and private investment money. As we stood on a third-floor balcony looking out at that site, we could see across the street to a homeless encampment.

Horan and Alvidrez will be at Rainbow’s grand opening Thursday. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and others will be there to rally support for state Proposition 1C and Los Angeles Measure H, the affordable-housing bonds that would fund, among other things, projects like Rainbow Apartments.

Measure H would only cost the average homeowner about $50 a year, but the developers who pitched the idea to the mayor and City Council have not come up with enough money to wage an effective campaign. The mayor should get even by implementing a housing policy that requires developers to include affordable housing in their projects.

If you’d like to learn more about Measure H or Proposition 1C, which are on the ballot because working people can’t afford to buy houses in California’s still-crazy market, go to SmartVoter.org for all the details.

But keep in mind, Alvidrez advises, that the housing bonds will create hundreds of construction jobs, and that with Measure H, $50 a year is a bargain compared with the price of the cops, paramedics, emergency room staffs, court and prison employees who now figure into the cost of churning a sick, homeless person through the system and kicking him out the other side without addressing any of his problems.

As we sat together in his room, Riddick told me he had a nightmare on his first night in the new place.

“I dreamed that demons were coming at me. Everybody was trying to get me. I asked myself how they got in here and then I realized I let them in.”

He didn’t need an analyst to explain the meaning. He’s got to stay clean and choose his friends wisely. After that, he said, his first goal is to reunite with his son and daughter. He had to pause before continuing, holding his head in his hands.

“I ain’t seen them since I buried their mother,” he said.

I asked how long he expected to be at Rainbow.

“I’ll be here till I get something better,” he said, telling me he wants to get a license for his shoeshine business and maybe go full-time at one of the downtown hotels.

And then where?

He took his hat off and leaned in close.

“I won’t be goin’ backwards.”

*

Reach the columnist at steve.lopez@latimes.com and read previous columns at www.latimes.com/lopez

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.