Planting themselves in Brazil

- Share via

Barreiras, Brazil — WHEN Brian Willott moved to these central Brazilian plains to fulfill his dream of farming, there was much to remind him of the home he left in the American heartland.

The sign at the end of a dirt lane proclaimed his rented land “Fazenda Kansas,” Portuguese for “Kansas Farm.” The flat fields stretching to the horizon teemed with cotton and soybeans. Billboards boasted familiar names such as Cargill, Monsanto and John Deere.

But the going hasn’t been as smooth as the level terrain. U.S. farmers have been the targets of squatters, thieves and scammers. Willott has discovered that slave labor still exists in the region. And there have been challenges few Midwesterners ever encounter: piranhas, deadly vipers and dengue fever.

You’d have to forgive Willott if he said, “We’re aren’t in Kansas anymore.”

Willott belongs to a small but growing number of U.S. farmers who are moving to this South American nation in the same way that European migrants headed west generations ago to settle the American plains. Like their ancestors, these pioneers see opportunity in the wide-open spaces of an up-and-coming agricultural powerhouse, and the chance to earn better returns than they could at home.

But they are also finding that unfamiliar language, a bare-knuckle frontier culture and their own naivete are obstacles to success. As if the learning curve weren’t steep enough, now Brazil’s agricultural sector is mired in the worst slump in decades. A strong real, Brazil’s national currency, is punishing farm exports. High oil prices have raised production costs. Prices for soybeans and cotton have fallen from lofty levels of a few years ago.

“There was all this hype and exaggerated optimism about Brazil,” said Pat Westhoff, an associate professor of agriculture at the University of Missouri who has studied the region. “There isn’t the fantastic short-term growth that people expected.”

Some American farmers already have packed it in. But Willott, who has yet to turn a profit since landing in 2003, said he was staying put.

The former agricultural economist believes that, despite its current woes, Brazil may one day supplant the United States as the world’s biggest farm producer.

In the meantime, he is tackling problems that can’t be solved by any computer model, such as how to ask a Brazilian woman out without getting slapped. (His advice: Throw out those grammatically stilted Portuguese language tapes that neglect to mention that a common dining term can be vulgar in everyday usage.)

“I’m learning lessons that I didn’t necessarily want to learn,” said Willott, 34. “But it’s an adventure.”

*

ESTIMATES of how many U.S. farmers have relocated to Brazil range from a few dozen to a few hundred. But the migration speaks to a staid American industry that is all but closed to newcomers.

Prime farm ground in the U.S. Midwest can sell for as much as $5,000 an acre, but sizable tracts rarely come on the market even at those prices.

In Brazil, land ready to farm can be had for $750 an acre and virgin soil for $100 or less an acre. And there is plenty of it. Nearly 100 million acres of scrubland known as cerrado in Brazil’s interior have been converted into productive farm ground, most in the last 25 years. It’s the biggest addition of arable land on the planet since homesteaders plowed the American prairie. But unlike the U.S. Midwest, the cerrado isn’t close to being settled. Yet Brazil is already an agricultural superpower.

Brazil is the world’s largest producer of coffee, tropical fruits, sugar and sugar-cane-based ethanol. Its 170 million head of cattle are the biggest commercial herd on the planet. Its chickens are served on tables worldwide. Farm products represent 40% of the nation’s exports.

With a sunny climate that allows producers to plant two or three crops a year, Brazil is attracting millions of dollars from U.S. investors looking to cash in. Hundreds of farmers in the United States have pooled their money to buy Brazilian farmland, hiring managers to run the operations. Others have come themselves.

But the gold rush has yet to yield the riches that many sought. Brazilians and some early American farmers here say the newcomers were gullible and cocky, overpaying for land and assuming that whatever worked in Iowa was going to cut it in Brazil. Investors say promoters peddled an idealized view of the country, neglecting to mention the many pitfalls, including grinding bureaucracy, heavy taxes, corruption, rickety infrastructure, tense labor relations and snarled land records.

“This isn’t for the faint of heart,” said Illinois lawyer Paul Idlas, who is battling to extricate his Brazilian farm from competing title claims. He said many of the so-called experts that gave him advice either didn’t know what they were talking about or were taking kickbacks from the sellers, or both. “It’s hard to know where the stupidity ends and the dishonesty begins,” he said.

*

STILL, few dispute Brazil’s long-term potential.

Willott, who grew up on a farm in Missouri and earned a master’s degree in agricultural economics, said he got a close-up look at how Brazil was reshaping global production during his work for a think tank at the University of Missouri, his alma mater.

“If there was something happening in the [commodities] markets in Chicago, usually it was related ... to something happening in Brazil,” he said. “It’s the biggest story in 100 years.”

Restless behind a desk, Willott chucked his university job, employer-paid health insurance and a retirement plan to roll the dice in Brazil. He moved in 2003 to Bahia state, where he started out cultivating 1,000 acres of soybeans and cotton on rented land.

“We wanted to start small so we could make our mistakes on the cheap,” said Willott, who is backed by half a million dollars in capital raised from savings and four U.S. investors. “You know the old motto: Be prepared.”

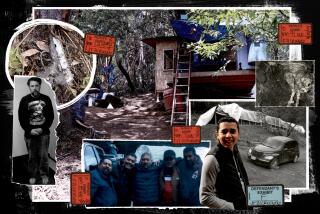

But even the former Eagle Scout, who stands 6 feet, 3 inches and weighs 250 pounds, couldn’t have girded himself for every contingency. Farming, it turns out, has been the easy part. Willott said he returned to his farm last year after a short visit to the United States to find that some local advisors had secretly used his cotton as collateral to obtain a bank loan. He said a cotton ginner tried to cheat him out of a truckload of his harvest. His accountant called him crazy for wanting to do everything by the book. Farms he has considered buying have turned out to have liens and title problems that the sellers failed to disclose.

Willott said Brazilian farmers chided him for paying workers too much, feeding and treating them too well. “They’ll see it as weakness,” Willott recalls them saying. An incident last spring convinced him that they might be right.

When disgruntled day laborers who weeded his cotton threatened a sit-in after a labor contractor ran off with the payroll, Willott agreed to make good on the debt.

But when he arrived at the union hall in the town of Luis Eduardo Magalhaes toting $4,600 in a grocery sack, he said the line of people demanding back wages had grown to include pregnant women, old men and passersby who had never set foot on his farm.

Lacking complete records from the contractor to expose the pretenders to labor officials, Willott resorted to some performing of his own. The amateur thespian who played the lead in his high-school musical became a Portuguese-speaking Perry Mason, tripping up the impostors with questions such as, “What color is the farmhouse?”

“Everybody made money on that deal but me,” Willott said. “In the Midwest you take people at their word. Here, you don’t know who to trust.”

One faithful companion is his dog Roo. The affectionate mutt leaps through the window of the dusty, silver 2003 Chevy pickup when Willott pulls into the driveway of his spartan home, where he has stored sacks of millet and soybean seeds in the living room and a tractor tire in the garden.

Another stalwart is his translator and assistant Manoel Santana Reboucas, a polite, religious man who is bent on fixing Willott up with one of the women from his church. Worship services are a popular activity in the frontier city of about 135,000 residents with few other legal diversions than bars and a one-screen movie theater.

“It gets pretty lonely,” said Willott, who spends his free time reading Brazilian farm magazines and devouring English-language classics he occasionally runs across in bookstores.

Willott’s 65-year-old parents, who farm 230 acres near Mexico, Mo., would like to see him come home.

He was absent for his grandmother’s funeral. His 8-year-old niece is growing up fast. His mother, Alice, worries that her son might be harmed by criminals or have an accident on the rutted roads. His dad, Jules, wonders whether he could find a way to buy or rent more land so that Willott could come back to Missouri to farm with him.

“When Brian was 5 years old he knew how many pounds of Atrazine 4L [herbicide] we were using,” said Jules Willott, paying as high a compliment as a taciturn farmer can pay his boy. “I knew at some point he would farm. I didn’t know it would be on the other side of the world.”

But Brian Willott is determined to succeed. He and his partners just rented a new 1,400-acre spread and are scouting for additional acreage. Soybean season has begun and cotton planting is just around the corner. He is mulling over expansion into eucalyptus and sugar cane. With land prices down and so many farmers in trouble, Willott said, this might be the time to buy.

“I rearranged my whole life to farm in Brazil,” he said. “I’m not coming home empty-handed.”

*

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.