‘Safe’ levels of lead may not be that safe after all

Efforts to reduce lead exposure in the United States have been a good news-bad news affair -- and the bad-news side of the ledger just got a bit longer.

Although the removal of most lead from gasoline and paint in the United States has driven exposure levels down -- way down from levels seen 30 years ago -- new research sharply lowers the level of lead exposure that should be considered safe. And it expands the population of people who need to worry about the toxic chemical.

Concern about lead exposure has long focused on children, who can suffer mental impairment and later fertility problems at elevated levels. More recently, children with blood levels of lead long considered safe have been found more likely to suffer from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Among adults, elevated levels of lead exposure have been found in recent years to raise the risk of high blood pressure and kidney disease. But now comes news that levels long considered safe for adults are linked to higher rates of death from stroke and heart attack. The latest study was published in the Sept. 26 issue of the American Heart Assn.’s journal, Circulation.

Researchers used a comprehensive national health survey of American adults to track 13,946 subjects for 12 years and looked at the relationship of blood lead levels and cause of death. They found that compared with adults with very low levels of lead in their blood, those with blood lead levels of 3.6 to 10 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood were two and half times more likely to die of a heart attack, 89% more likely to die of stroke and 55% more likely to die of cardiovascular disease. The higher the blood lead levels, the greater the risk of death by stroke or heart attack.

The dangers of lead held steady across all socioeconomic classes and ethnic and racial groups, and between men and women.

Study authors acknowledged that they were unsure how lead in the blood impaired cardiovascular functioning. But they surmised that it might be linked to an earlier finding: that lead exposure stresses the kidneys’ ability to filter blood. Lead may also alter the delicate hormonal chemistry that keeps veins and arteries in good tone, the authors wrote.

Federal standards, however, don’t reflect the new research. Although almost 4 in 10 Americans between 1999 and 2002 had blood lead levels in the newly identified danger range, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the federal agency that regulates toxic exposures in workplaces, considers up to 40 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood to be safe for adults. And recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention allow for up to 10 micrograms per deciliter for women of childbearing age.

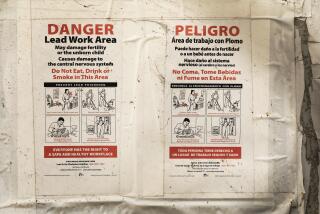

Paul Muntner, an epidemiologist at Tulane University and one of the study’s authors, says the findings suggest strongly that the federal government should revisit the limits of lead exposure it considers safe for adults. In total, about 120 occupations -- including roofing, shipbuilding, auto manufacturing and printing -- can bring workers in contact with high levels of lead.

For individuals, Muntner adds, the study underscores that every small bit of prevention is worth the trouble. Worried consumers can purchase lead-detection kits from hardware stores.