Please come home

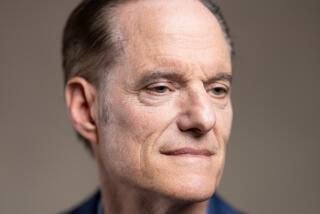

I miss Harvey Weinstein. Not the Harvey Weinstein you see today, the slimmed-down mogul who’s acquired the Halston fashion brand, invested in a MySpace-style website for the rich and famous and bought the Ovation arts channel. Not the Harvey Weinstein who told the Hollywood Reporter last year that “we are focused on other areas outside of film.”

The Harvey Weinstein I used to know -- the Oscar impresario who collected gifted young filmmakers the way Tiger Woods accumulates golf titles -- was truly, madly, deeply in love with movies. He was the man behind “City of God,” “Amelie,” “Shakespeare in Love,” “Pulp Fiction,” “In the Bedroom,” “sex, lies, and videotape,” “Trainspotting” and “Sling Blade,” to name but a few.

Today’s Harvey has lost his way, not to mention his magic touch. Since he cut his ties with Disney, leaving his Miramax label behind and starting the Weinstein Co. with his brother Bob at the end of 2005, he seems to have lost his passion for making the kind of classy fare that earned him an unprecedented string of 11 consecutive Oscar best picture nominations.

He’s become a clone of his brother, the guy who kept Miramax in the black during lean years with horror spoofs and action fare. When today’s Harvey points to the Weinstein Co.’s successes, he finds himself boasting about Bob movies, be it “Hoodwinked,” a crass takeoff on “Little Red Riding Hood,” or “Scary Movie 4,” a scatological movie spoof that squeezed a few last laughs out of the brothers’ old Miramax franchise.

Too much of the rest of the Weinstein Co. slate has aimed low and missed. Harvey’s Oscar slate was full of fizzles, led by the dramatically inert “Bobby” and the woeful “Factory Girl,” which got more buzz for its last-minute re-editing than its artistic ambitions. The latest failure is “Grindhouse,” an expensive attempt to relive the glory days of ‘70s exploitation cinema. The 192-minute movie won admiring reviews, thanks to Quentin Tarantino’s gleefully kinetic “Death Proof” segment, but has flopped at the box office, dropping off a brutal 63% in its second weekend, grossing only $19.6 million in 10 days of release.

I feel like putting Harvey’s picture on a milk carton. Has anyone seen the crazy, spittle-spewing, chain-smoking hustler who would bellow insults, twist arms and shamelessly hype whatever movie was due that week? I miss the old Harvey, the man who would’ve locked “Grindhouse” auteurs Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez in an editing room until they cut 40 minutes out of their movie. I miss the old Harvey, the cinema carnival barker whose passion for film was often indistinguishable from his paranoia, abusive behavior and vitriol.

No one has ever screamed at me over the phone the way Weinstein did -- the obscenities and insults rolling off his tongue like sweat off a boxer. The new Harvey, who called the other day after writing me a three-page letter defending his aspirations, doesn’t yell anymore. He’s feisty, funny, even apologetic about getting off track, noting that he doesn’t smoke or eat sugar anymore, which he blames for his old temper tantrums.

He insists that, after spending 18 or so months building a company infrastructure, he’s focused on making good movies again. “I’m going to give them the old Harvey -- but with charm,” he says. “Dressed in Zegna, with cool ties picked out by my girlfriend. Maybe if I’m better dressed and more charming, I’ll go over better.”

(To read the entire interview with Weinstein, go to latimes.com/entertainment.)

BUT I still miss the old Harvey, who used to confront filmmakers when they were arrogant or indifferent to audience concerns, as he did when he got into a screaming fight with Tarantino in the lobby of a multiplex in Seattle over the filmmaker’s refusal to trim “Jackie Brown.” That was the Harvey who almost single-handedly dragged independent film into the commercial mainstream, championed young film talent and turned the Oscars into a brilliant marketing weapon for his art-house acquisitions.

But since the Weinstein brothers launched their own company with Wall Street money, things have changed. In the old days at Disney under Michael Eisner’s iron fist, the Weinsteins were prevented from empire building, stopped from buying indie film companies or cable channels, not to mention from pursuing a larger investment in “The Lord of the Rings” and various Manhattan real estate opportunities.

Now, freed from Disney’s corporate ball and chain, he is Harvey Unbound. He’s acquired a home video company. He’s producing stage musicals. He’s boasted to friends about conquering the Internet and the fashion world. When a Wall Street Journal reporter asked if he might be spreading himself too thin, Harvey signaled his level of aspiration with his reply: “So what would you tell Rupert Murdoch? Please just stick to broadcasting and newspapers? Don’t buy a company like MySpace?”

Longtime Harvey watchers say this fierce desire to be a media kingpin is deeply embedded in his psyche. It’s easy to forget that when Bob and Harvey first came to Hollywood they were scruffy outsiders with all the panache of a pair of telemarketers. A longtime agent recalls meeting the brothers in the late 1980s holed up in a cigarette-butt-strewn suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Huddled on the phone, they were in the midst of an intense round of negotiations, as if buying a hot movie property.

Finally, the visitor asked their assistant what on Earth was going on. He rolled his eyes. “They’re trying to maneuver their way into Irwin Winkler’s poker game.”

Harvey is the opposite of Groucho Marx -- if anyone has a club, he’s dying to be in it. In the early days, Weinstein’s burning desire to succeed went hand in hand with making great movies. But today he seems enamored with status consciousness, in danger of being more of a boldfaced media personality than a real human being.

It’s an old Hollywood story, the great salesman being seduced by his own spiel. Peter Guber could charm the monkeys out of the trees, but once he assumed the studio throne at Sony, he lost his mojo. Despite having Hollywood under his spell for years, after Michael Ovitz left CAA he discovered that it wasn’t as easy to create a new empire a second time around.

Insiders say the Weinstein Co., without the deep pockets of a big studio, is outgunned in the marketplace. The brothers are said to be indecisive, surrounded by young, inexperienced executives. Gone from the ranks are such formidable talents as acquisition chief Agnes Mentre, Chief Operating Officer Rick Sands, marketing chief Mark Gill, production chiefs Meryl Poster and Jon Gordon, foreign sales chief David Linde and Executive Vice President Charles Layton.

The outside world has changed too. Bob Weinstein’s genre success has been outstripped by Screen Gems and Lionsgate while Harvey’s Oscar domination has been challenged by Paramount Vantage, Fox Searchlight, Focus and the new Miramax. Harvey remains a canny media wrangler, hypnotizing credulous reporters with tales of upcoming triumph. But the boasts now ring hollow.

Eager to impress investors last fall, he bragged to the Wall Street Journal that he was releasing two “giant movies” that would become franchises. One was “Hannibal Rising,” a Hannibal Lecter horror movie that bombed in February. The other was “Arthur and the Invisibles,” a hyperactive kid-flick that was panned by critics and barely managed to crack the $15-million mark after its January release here.

Now, after the failure of “Grindhouse,” Bob told the New York Times that the company’s real ace in the hole is its “sneaky little” direct-to-video business that will keep the Weinsteins in profit. The key word there is “sneaky,” since the word for the kind of movies that get direct-to-video releases would be “schlock,” as in cheesy horror movies or lowbrow comedies.

I want the old Harvey back, the spellbinder who could just as happily tell stories about Ben Hecht as promote what he was buying at Sundance. But that Harvey is gone, replaced by someone whose Zegna suits only make him look like Broderick Crawford in “Born Yesterday,” a wheeler-dealer trying to pass as a smooth operator.

Harvey used to be crass, but the movies he made were full of class. Now, all too often it’s the other way around. I guess Joni Mitchell was right. Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.

*

The Big Picture appears Tuesdays in Calendar. Questions or criticism can be e-mailed to patrick.goldstein@latimes.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.