Second person singular

YOU want to write a novel about the failed marriage of two cultured, middle-aged New Yorkers, but you don’t want to write a conventional story about latte-sipping, museum-going, New York Review of Books-reading stereotypes. What do you do? You make the stories they tell themselves about their marriage the real story, showing the discrepancy between the facts and what they remember, or what they tell their friends, or what one of them later puts in a novel.

“You” is the 11th novel by Jonathan Baumbach, who over the last quarter-century has become something of a legend in the world of independent literary publishing. In 1973 he co-founded (with Peter Spielberg) Fiction Collective, which published innovative fiction of limited commercial appeal (and still does as the revamped FC2). His latest novel and latest publisher adhere to those noble principles, and the results are beguiling.

The novel is divided into three unequal parts. In the first, the reader is addressed as “you,” and while you naturally assume that it is indeed you the narrator/novelist is confiding in -- an informal update on the “dear reader” convention of older fiction -- it soon becomes apparent that he is addressing an unnamed woman. He then launches into a disjointed account of how they met and the various crises in their relationship -- though “crises” is too strong a word for their mundane misunderstandings -- confessing that he has a history of confusing reality “with the more compelling narrative of my fantasies.”

In part two, we get the woman’s version of things, narrated sometimes in the third person, sometimes in the first, and equally unreliable: “I forget (I forget a lot of things),” she admits after telling her version of how they met and of the bland marriage that ensued. The brief part three is again narrated in the first person by the husband and takes place several years later, after their divorce, when he runs into a woman who may or may not be his former wife.

You finish the novel not sure whom to believe and with no way of knowing which of the versions of their relationship is correct, if any. The wife is especially complex. One of Baumbach’s earlier novels is about a man’s seven wives; the wife here seems like seven women, or like a woman in a Cubist painting seen from seven angles simultaneously. By now, of course, you have realized that you’re not the author’s confidant, as the opening paragraphs led you to believe, but only an eavesdropper, picking up pieces of the story and supplying your own coherence.

Baumbach’s characters remind you how much fiction-making takes place in daily life: When the wife tells the husband she has some news, he quickly imagines three possibilities (and then Baumbach spins out three alternating stories based on those possibilities). Disappearing one night during their married life, the husband the next day is said to be “dying to market the version he had worked up of where he had been and what he had done.” Composing a personals ad for what must be the New York Review of Books, the wife “barely recognized herself in the description she was issuing.” We all work for the fiction collective, inventing and marketing stories as often as any novelist.

Baumbach drops many hints that “You” is autobiographical, but that would only add another layer of fiction to the fictions his characters tell. “Writing a novel . . . is a gesture of love between writer and reader,” he tells us early, so whether the “you” he addresses was inspired by an actual woman doesn’t matter: The finished book is indeed for you the reader. “For as long as I’ve known you, you’ve been an admirer of the bold and unexpected.” (Yes, you think, he’s got my number.) “The book I am writing with you in mind will be nothing if not unexpected.”

He keeps his promise: There is the unexpected alternation between first- and third-person points of view. There is the totally unexpected revelation that the wife’s name is V. Lois Lane, former lifestyle editor of the Daily Metropolis. There is “The Terror, a recently opened Middle Eastern restaurant with a provocative menu.” It is also unexpected that these postmodern tactics and gags can mesh so well with an old-fashioned story of midlife married malaise.

Writing a novel like this is indeed a gesture of love: Neither the author nor the publisher is in it for the money, and “You” probably won’t make it onto any bestseller lists. You may even have trouble finding it in a bookstore. But if you are “an admirer of the bold and unexpected,” “You,” like any gesture of love, deserves your regard.

--

Steven Moore is the author of several books on contemporary literature.

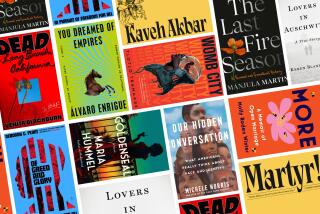

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.