U.S. patrol ship on alert in gulf

ABOARD THE USS FIREBOLT — Every day the 30 sailors on this coastal patrol ship in the Persian Gulf are on alert. At 170 feet in length, the Firebolt and similar craft are the smallest and possibly the most lightly armed vessels in the U.S. Navy.

Soon the Firebolt will be joined in the region by one of the Navy’s most heavily armed behemoths: the 1,092-foot-long carrier John C. Stennis, with a crew of 5,000 and more than 80 warplanes. The Stennis will head a strike force of destroyers, cruisers and submarines deployed to the region by the Bush administration amid heightened tensions with Iran over its nuclear program and allegations of Tehran meddling in Iraq.

Despite their differences in size and weaponry, the Firebolt and the Stennis share a stated mission: deter the Iranian navy from hostile acts in an area vital to oil shipments by showing Tehran that the strength of the U.S. military remains formidable despite its entanglements in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Iran, for its part, has begun an air and naval exercise, and has announced that it has tested a missile capable of sinking a large ship. In November, the Iranian navy released pictures of mines it said could be used to deny access to the Persian Gulf by ships considered “invaders.”

Although there is no denying that the Stennis and its strike force bring with them the ability to attack Iran’s nuclear sites, officials in Washington and Tehran appear to be focusing on the near-term threat of a naval confrontation.

Such a clash could be disastrous for the world’s oil supplies, 40% of which pass in tankers through the Strait of Hormuz, a 34-mile-wide choke point at the southern edge of the 600-mile-long gulf.

Vice Adm. Patrick M. Walsh, commander of the U.S. 5th Fleet, based in Bahrain, said the Iranians, by conducting live-fire missile exercises near the strait, had created “an environment of intimidation and fear” among gulf nations.

“We will continue to stand by our friends in the region,” Walsh said in an e-mail to The Times.

The Iranians, however, view any American presence in gulf waters as a provocation and security threat, and have repeatedly issued warnings that they have the ability to attack U.S. ships by using drone aircraft, small boats and missiles.

In testimony before Congress two weeks ago, Admiral William J. Fallon, President Bush’s nominee to be commander of U.S. Central Command, said it was clear from the Iranians’ recent military acquisitions and showy exercises that their main strategy was to “deny us the ability to operate in this vicinity.”

Asked by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) whether the Iranians had the ability to close the Strait of Hormuz, Fallon responded that he would be glad to answer -- in closed session.

Iran has deployed mines in the gulf before. In April 1988, near the end of the Iran-Iraq war, the guided-missile frigate Samuel B. Roberts nearly sank after hitting a mine while escorting oil tankers. After determining the mine was Iranian, the U.S. sank two Iranian warships and six armed speedboats in what was called Operation Praying Mantis.

In July of that year, the guided-missile cruiser Vincennes, which had been sent to the gulf to protect the Roberts as it left the waterway, mistakenly shot down an Iranian airliner, killing 290 people. The Vincennes’ captain said he believed the airliner was a military plane attempting a strike.

Analysts suggest that Iran’s current strategy might be to trap U.S. ships in the gulf by laying mines at the Strait of Hormuz, or by launching an attack using its three submarines.

The Iranians have boasted that their Russian-built diesel-powered submarines are so quiet that the vessels have been able to operate within striking distance of U.S. ships without being detected. The chief of the Iranian navy is a submariner.

But analysts say that closing the Strait of Hormuz, even briefly, could prove economically disastrous for Tehran, given its dependence on its oil exports.

“They may be religious enthusiasts, but they’re not stupid,” said John Pike, director of GlobalSecurity.org, which analyzes military trends. “They play things so close to the line that without oil revenue, they could be finished.”

Part of the Iranian strategy is to have, in effect, a navy within a navy. The Revolutionary Guard’s navy, which acts somewhat independently of the regular navy, has hundreds of boats that could be used to “swarm” American ships, analysts say.

Although the U.S. could sink many of the boats quickly, some might be able to inflict enough damage to allow the Iranians to claim a symbolic victory, analysts say. But in recent years, the U.S. has armed its smaller ships with weapons that can repel smaller craft.

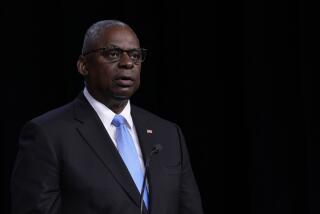

Any pledge to keep the Strait of Hormuz open, Walsh said, “must have sustainability, visibility and muscle for it to be credible.” To provide extra muscle, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates ordered the Stennis to join the carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower in the region.

Technically, the Navy will not confirm that the Stennis will be in the gulf, suggesting that it could be stationed in the Gulf of Oman, just outside the Strait of Hormuz, or much farther south, off the Horn of Africa.

While it awaits the arrival of the Stennis in the region, the Firebolt’s crew keeps a wary eye on the two Iraqi oil terminals in the gulf. Crew members are convinced that if the U.S. and Iran are headed for confrontation, they’ll be in the middle of it.

“If we have to go to close quarters, we’re going to see a lot more than the guys on the big ships,” said sailor Douglas Stevenson, 28, of Erie, Pa. “This is why we signed on the dotted line.”

Times staff writer Peter Spiegel in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.