Antiviral drug stops working vs. flu strain

- Share via

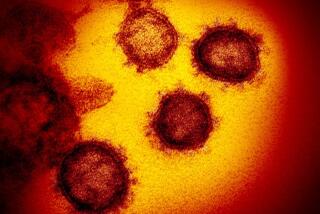

A milder than usual U.S. flu season is masking a growing concern about widespread resistance to the antiviral drug Tamiflu and what that means for the nation’s preparedness in case of a dangerous pandemic flu.

Tamiflu, the most commonly used influenza antiviral and the mainstay of the federal government’s emergency drug stockpile, no longer works for the dominant flu strain circulating in much of the country, government officials said this week.

Of samples tested since October, almost 100% of the strain -- known as type A H1N1 -- showed resistance to Tamiflu.

In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued new guidelines to physicians in December. Doctors were told to substitute an alternative antiviral, Relenza, for Tamiflu, or to combine Tamiflu with an older antiviral, rimantadine, if the H1N1 virus was the main strain circulating in their communities.

Each flu season, several types of flu viruses circulate, and various ones can dominate in different regions and times. Only the H1N1 virus is showing signs of Tamiflu resistance, CDC officials said, speaking at an influenza conference in Washington.

Other flu viruses currently circulating are not Tamiflu-resistant.

Each year, the three most prominent flu strains -- two type A’s and one type B -- are chosen for the creation of the flu vaccine. Unlike last year, both of the A viruses matched this year’s vaccine, although the B did not, officials said.

Public health experts recommend flu shots as the best way to avoid the virus.

Health officials have long urged constraint in using antivirals out of fear that, as with antibiotics, misuse could lead flu viruses to develop a resistance, rendering the drug ineffective when it was truly needed.

Tamiflu, which is known generically as oseltamivir, and Relenza, or zanamivir, came on the market 10 years ago. They were hailed as being more effective at treating the flu and having fewer side effects than the older antivirals rimantadine and amantadine. They were also lauded as being much less prone to develop resistance.

Tamiflu and Relenza have been stockpiled by the federal government for treating the public in case of the emergence of a dangerous pandemic flu. Four times as many Tamiflu doses have been stockpiled as Relenza doses.

Some microbiologists have argued that Tamiflu is more likely to develop resistance than Relenza. Therefore, they say, Relenza should make up at least 50% of the stockpiled antivirals.

“There have been people, and I’m one of them, that have suggested that there be more of an equal stockpiling of oseltamivir and zanamivir,” said Dr. Anne Moscona, a pediatrician and professor of microbiology and immunology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Both drugs reduce the replication of influenza viruses by blocking an enzyme called neuraminidase. To do so, they slip into a pocket in the enzyme. The pocket has to change shape to accommodate Tamiflu, but not Relenza. If a mutation in the virus stops the pocket from changing shape, Tamiflu can no longer slip in to do its work, Moscona said.

Tamiflu became the more popular drug because it can be taken orally in pill or liquid form, whereas Relenza must be inhaled and can’t be used by young children or the elderly.

What mystifies infectious disease experts and microbiologists is that the Tamiflu-resistant strain now circulating appears to be a mutation that spread naturally, not as a response to antiviral use.

“We don’t think it’s due to overuse,” said Dr. Anthony Fiore, a CDC epidemiologist. “There’s not as large amount of use of oseltamivir as there might be with antibiotics.”

Influenza viruses are RNA-based, which are error-prone when replicating. This means they change rapidly, Fiore said. If a change occurs that confers an advantage of some sort, then it’s likely to be passed on.

Viruses also swap genes among themselves, and one fear is that the resistance mutation will be passed on to other flu viruses, including the deadly H5N1 bird flu circulating in Asia.

For now, H5N1 responds to Tamiflu, although it must be administered early. The virus is more than 60% fatal in humans.

--