For Christian enclave in Jordan, tribal lands are sacred

- Share via

Reporting from Fuhays, Jordan — Michel Hattar’s father was a priest in Jerusalem in 1947 when word arrived from the rocky Jordanian hills that he must renounce his vows and marry to protect his tribe’s land and inheritances.

He did as he was told. He broke from the holy order he had known for 20 years to wed the bride picked by his family, his first cousin, Widad. Today their son Michel lives on a bluff of olive groves and fig trees that slopes toward the valley that his Fuhays tribe has farmed and fought over for more than four centuries.

This Christian enclave west of the Jordanian capital, Amman, is ringed with steeples and religious devotion, but for every Bible parable there is a tribal tale, usually one that ends with someone outfoxed or dead. Clan loyalty sets boundaries, keeps the peace and runs on customs, such as sprinkling extra salt into a meal to let a guest know he is welcome. If there’s no salt, it’s wise to make a hasty exit.

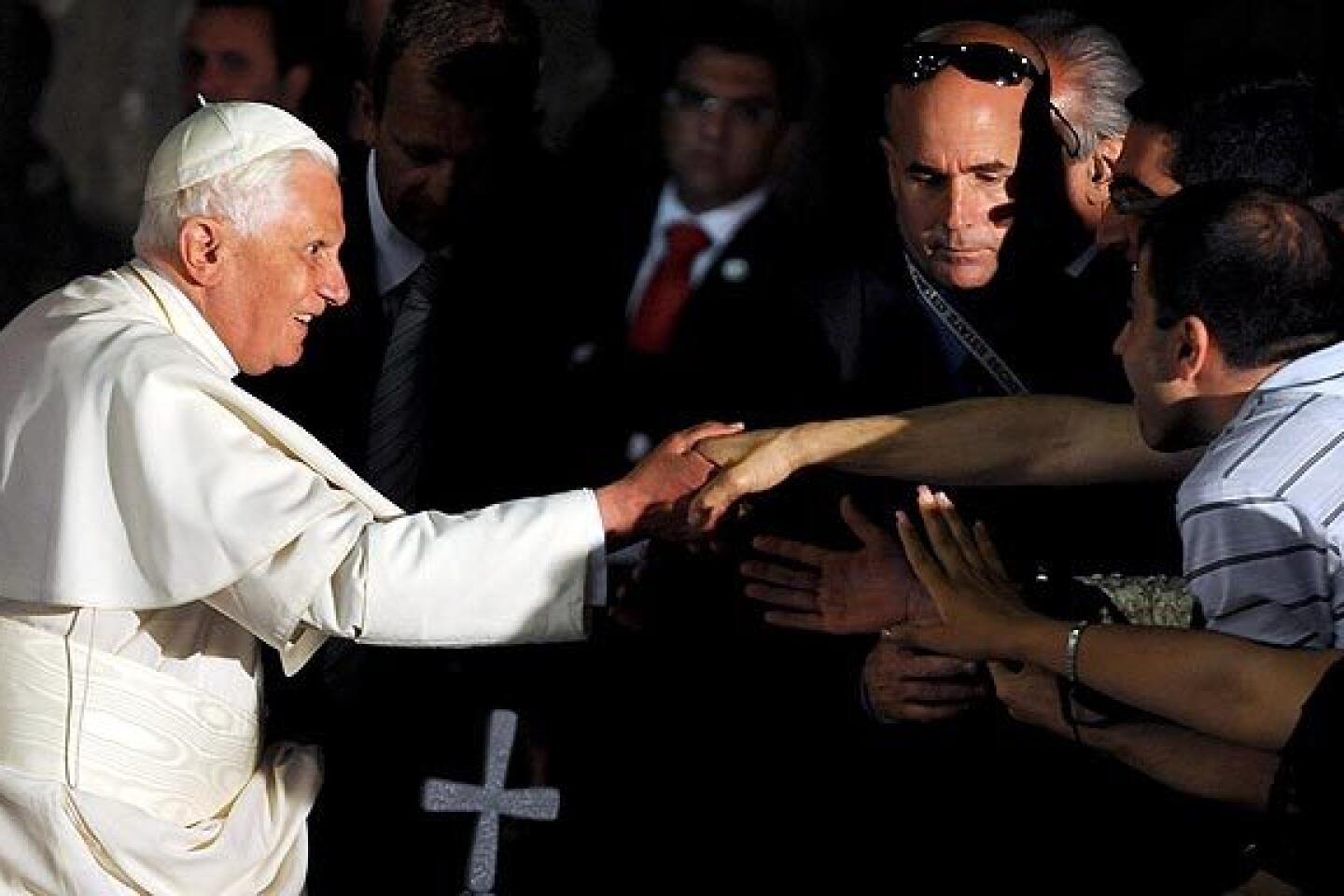

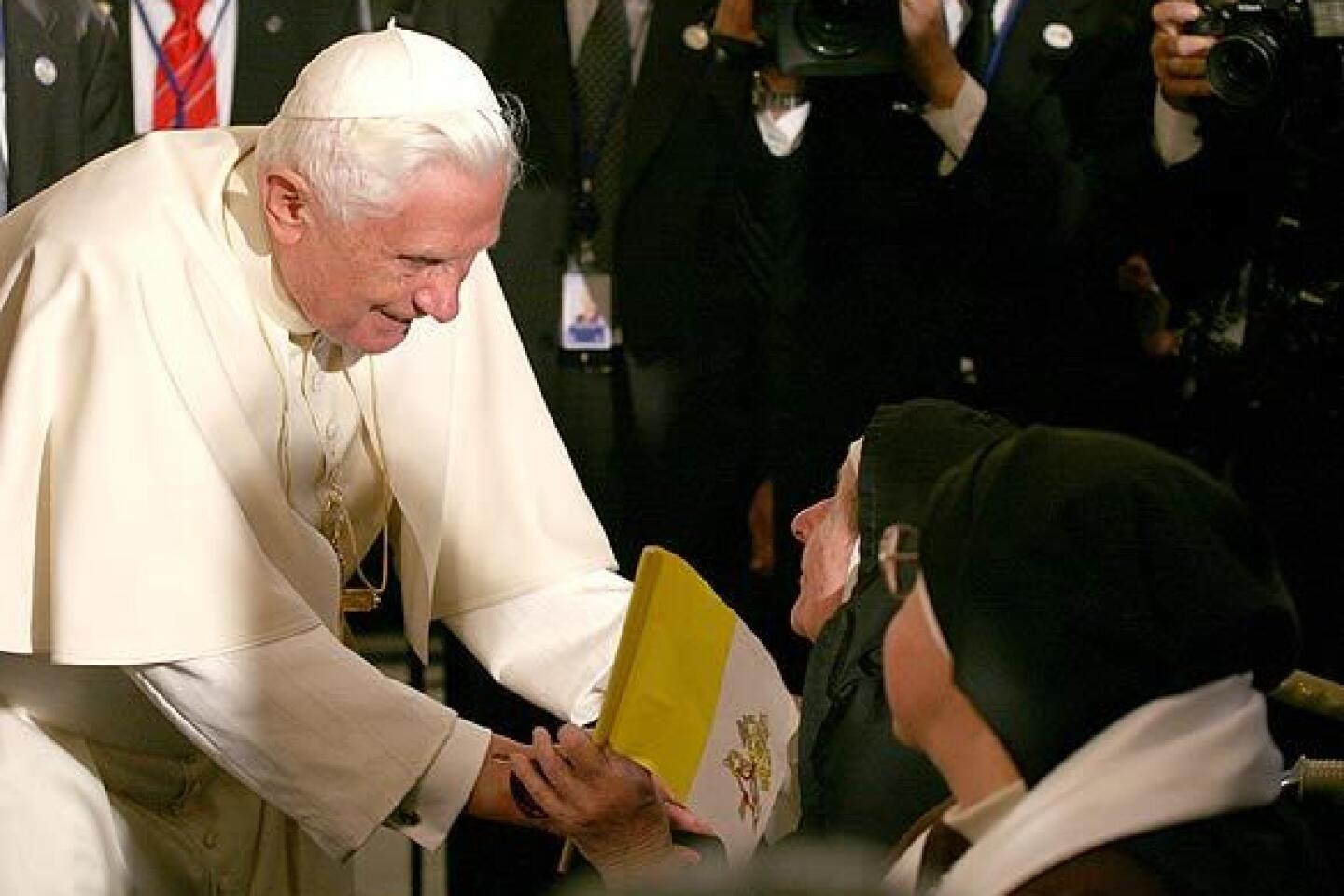

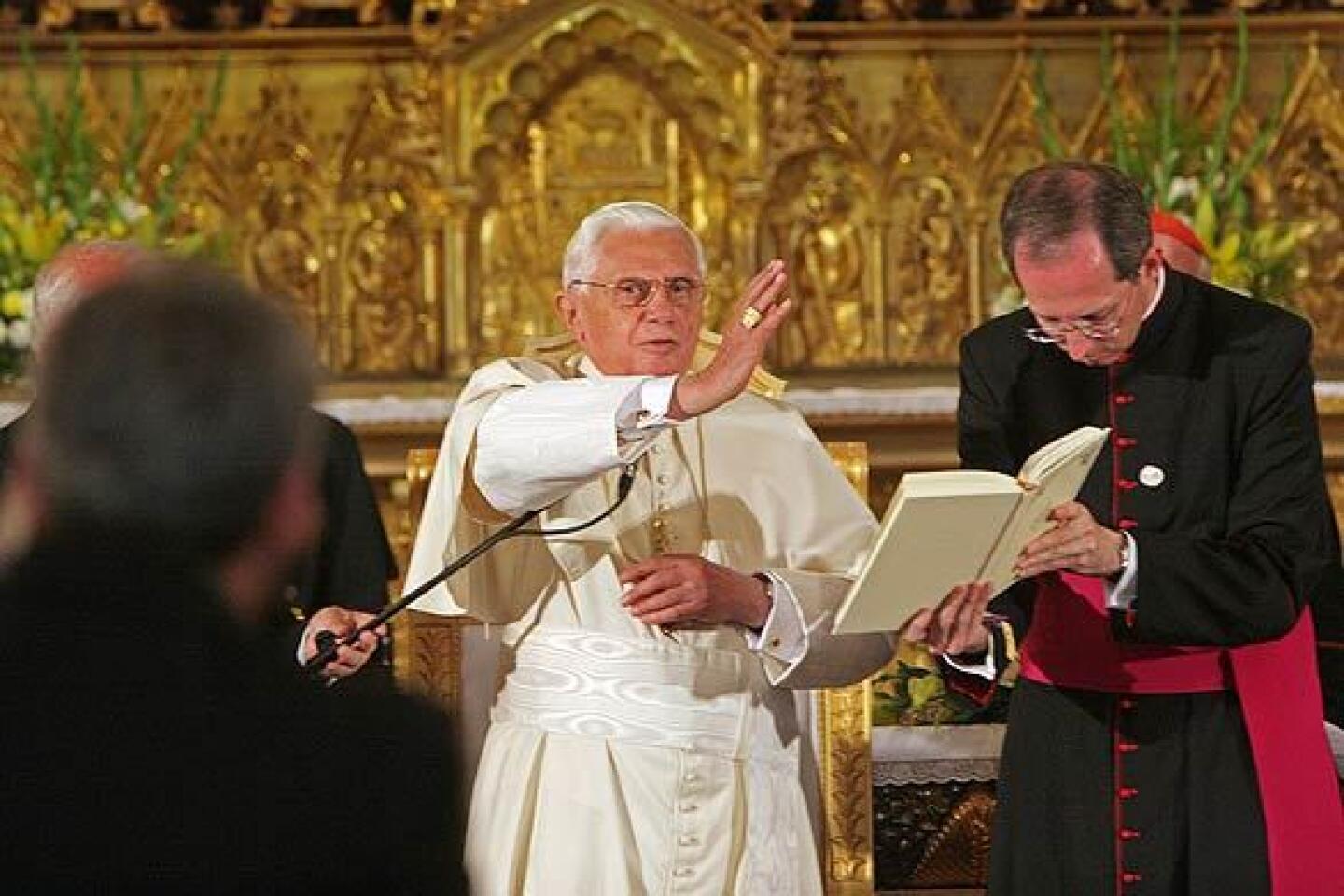

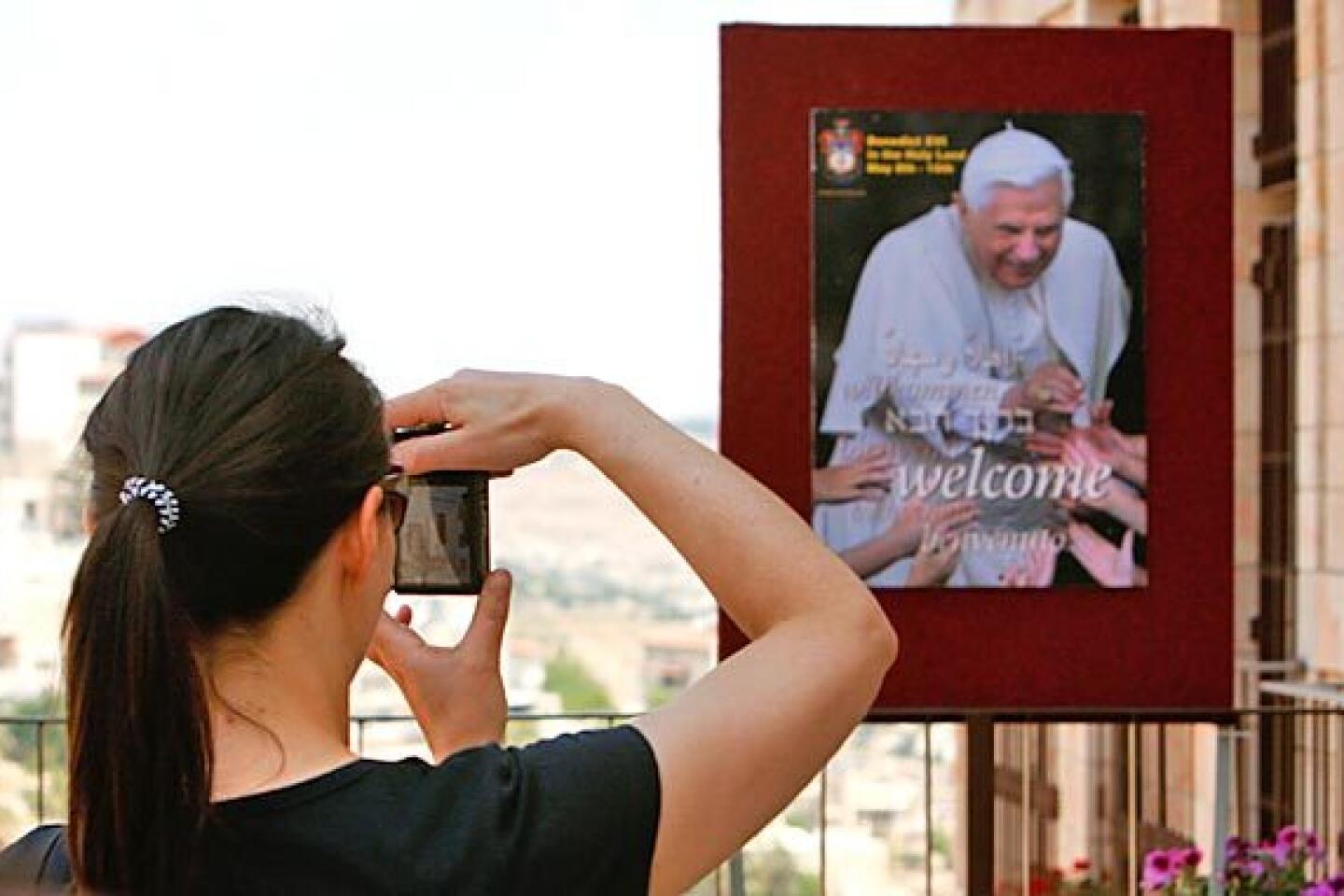

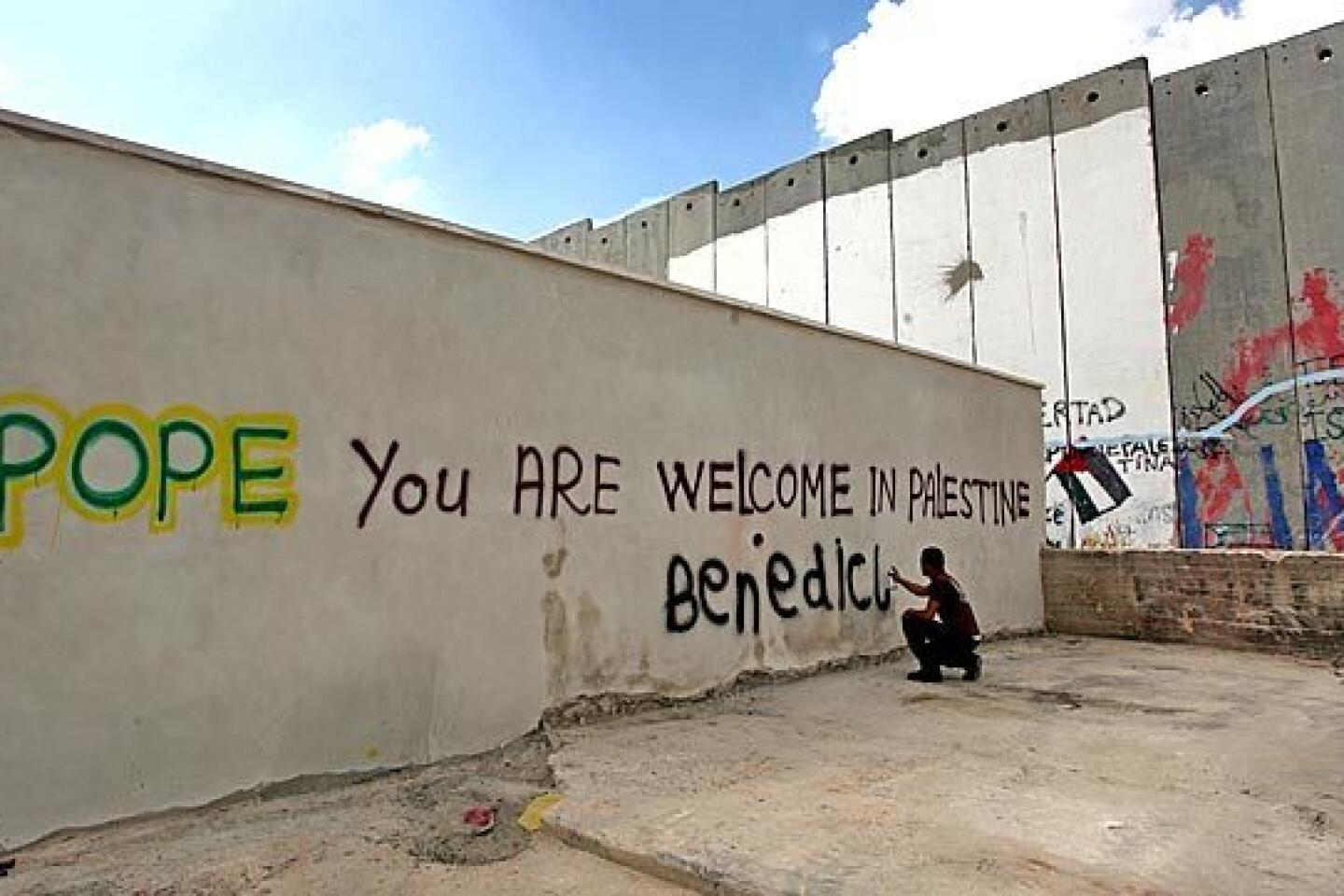

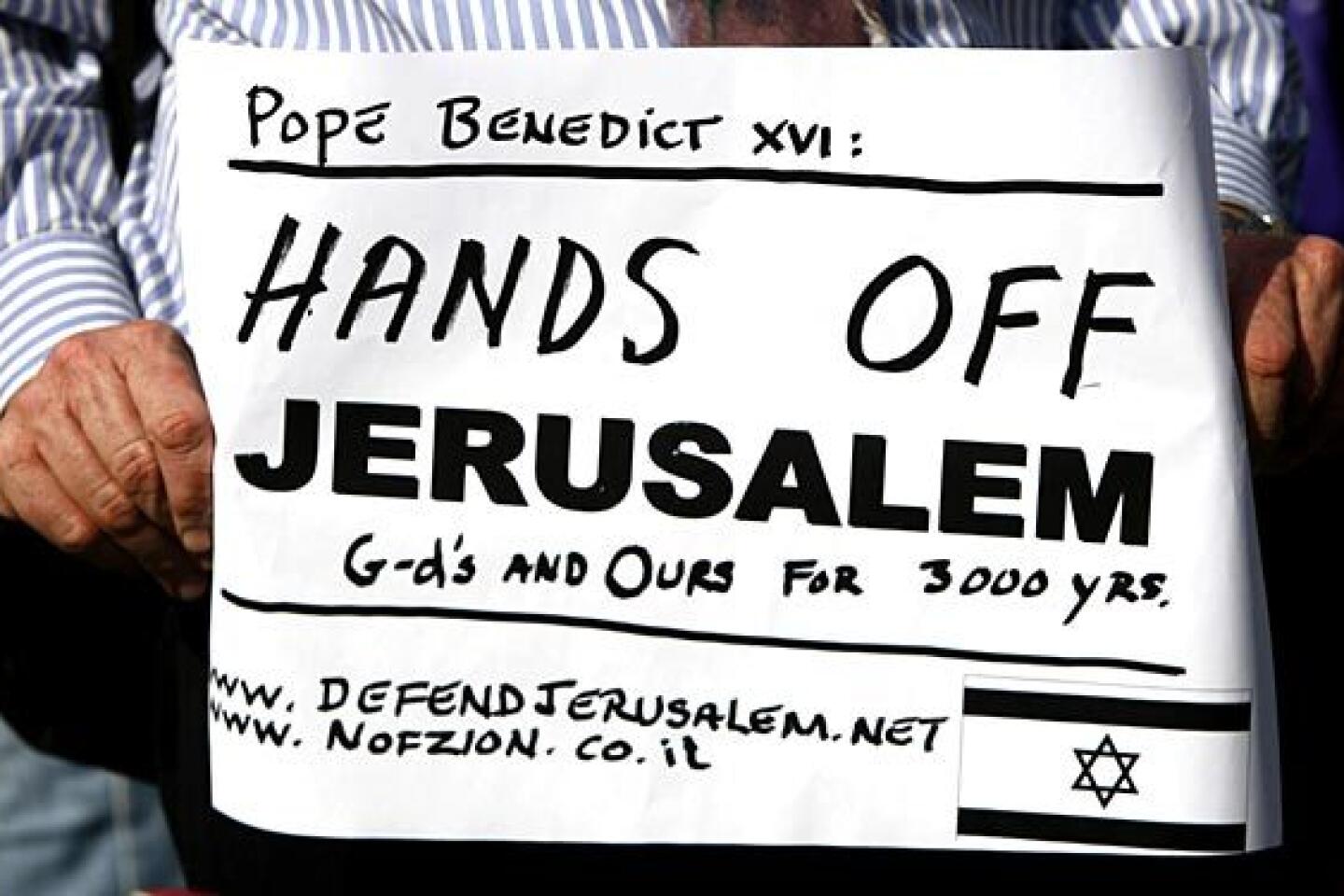

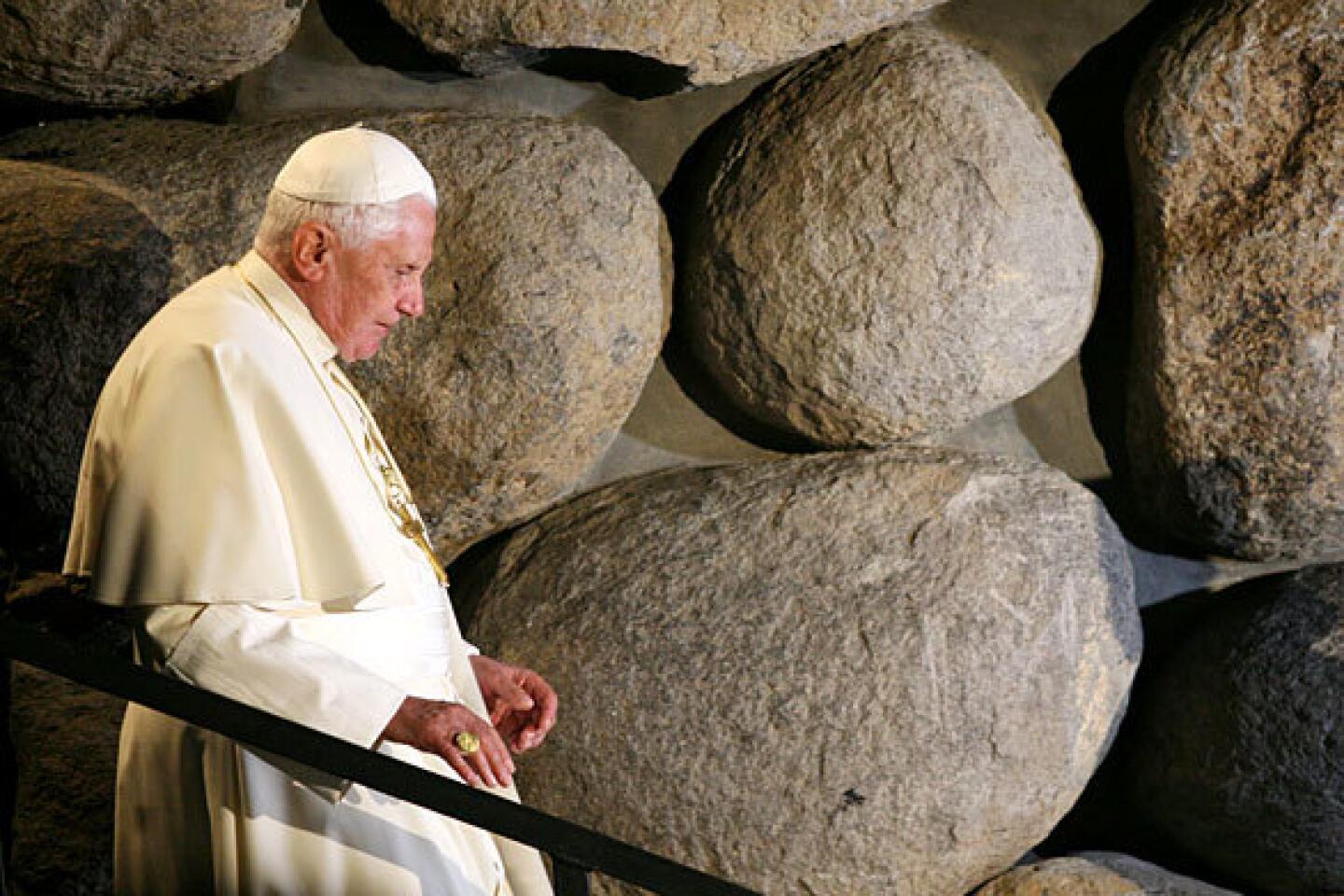

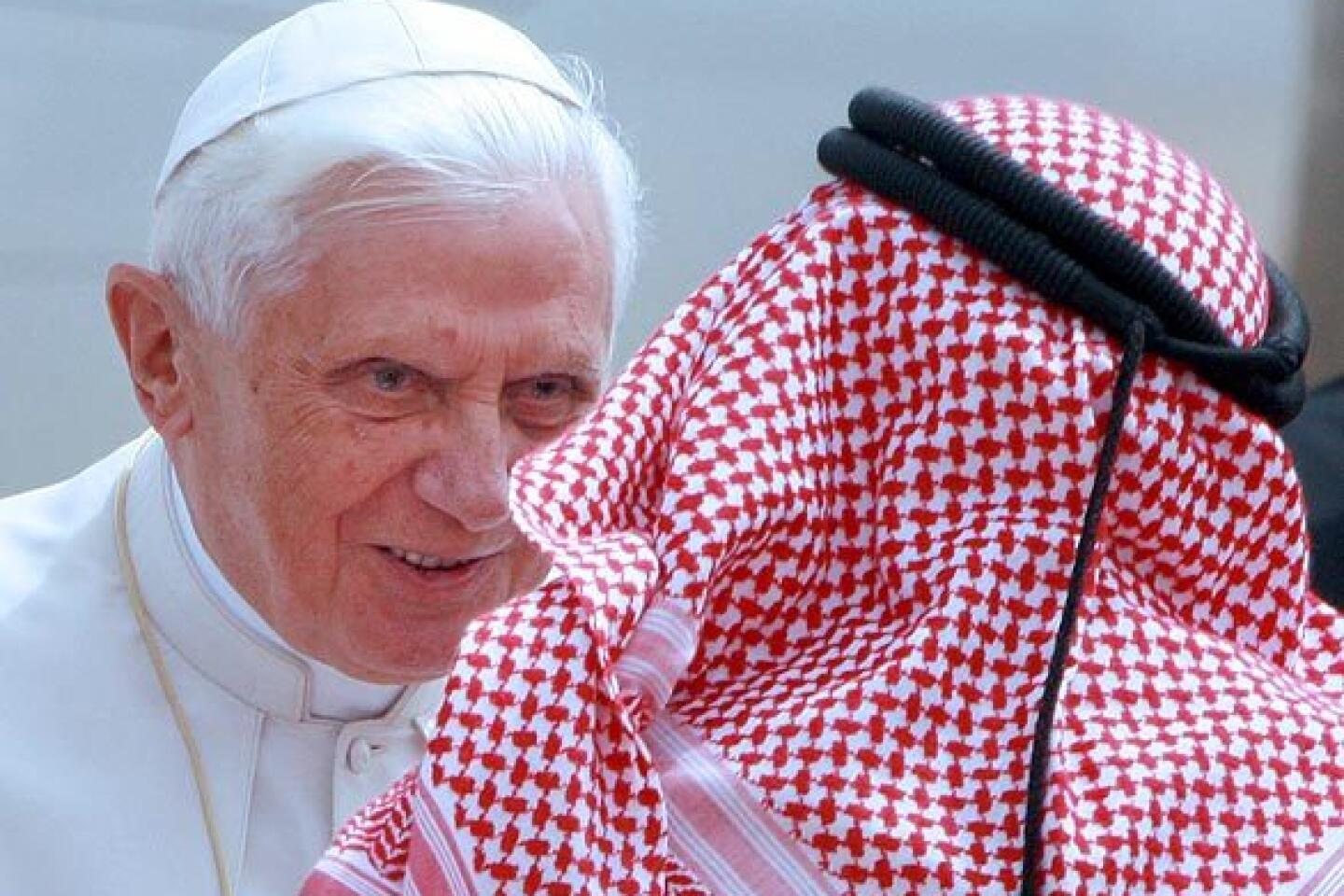

Hattar, a balding man with white hair and dark eyebrows, sits in his home near a statue of the Virgin Mary. There’s wind and anticipation outside. Pope Benedict XVI is in Jordan on a three-day pilgrimage to improve relations between Christians and Muslims. Hattar says that’s a noble effort, if perhaps more spiritual than practical, and besides, the pope is too friendly with the Jews across the border in Israel.

“You know, coexisting with Muslims is difficult,” he says, choosing his words so as to convey truth but not offend. It is the way of conversation here, to let nuance reach the heart. “Muslims don’t accept others. They want everyone like them. We show them friendship. They don’t show outward hostility, but you feel it inside your soul.”

In 1950, Christians made up about 30% of the Jordanian population. That’s dropped to less than 4% in this overwhelmingly Islamic nation where Jesus was baptized and Moses was buried. Most Christians, like Hattar’s brother and four sisters, left for better opportunities in Europe, the United States and Canada.

Holding on to tribal lands is approached with more sanctity than taking Communion; when a Palestinian recently bought property on the hillside, Hattar went down to make sure his new neighbor had the New Testament, not the Koran.

“We don’t sell land to Muslims. We don’t want mosques amidst us,” he says. “Once, in the 1960s, a Christian man from the tribe wanted to sell his land to a Muslim. The priest gathered other men and they went to this man’s house. They asked him, ‘Why are you doing this?’ He told him he needed money, 10,000 dinars. The priest and the men gave him 10,000 dinars and then they beat him and threatened to kill him if he ever sold land to a Muslim.”

Hattar fishes up another story, one to show that life in the hills is also calibrated on respect and mutual interests.

Once, centuries ago, an Arab warlord from deserts away wandered in and wanted to marry a Christian girl from a Fuhays tribe. The elders were opposed and secretly sought help from a neighboring Muslim clan, which didn’t want a foreign interloper, even if he practiced Islam, among them. The Muslim clan told the Fuhays to invite the warlord to dinner, but to put no salt in his food. When the intruder tasted his meal, he knew he wasn’t welcome, but when he tried to escape, the Muslim clan surrounded him and cut off his head.

Devotion to the land is rooted deeper in the soul than religion, and tribes in this country -- no matter their creed or enmities -- unite against a common outside enemy. It’s a story as unyielding as the hills, where gusts blow so hard pine trees grow slanted and seeds scatter if not pushed down into the ground.

Hattar walks upstairs to his roof; before him, the valley unfurls like a kicked rug and narrows in the distance where a road disappears into the shadow of another spine of hills. This land used to have many more shepherds, including one -- yet another story -- who walked into a butcher’s shop years ago. He sat and lighted a cigarette and stared at a painting of a bearded man with a glow around him, tending sheep. It was Jesus, but the shepherd did not know about Jesus, so he asked the butcher: “Is that your father?”

Hattar laughs. That is a tale told often in the markets, on the ridges.

“This is my land, olives, figs and grapes,” he says. “The pope doesn’t understand the complexities of the region. But I’m a Catholic, so I defend him. He won’t be around forever.”

He walks downstairs, past blocks of dried yogurt that look like stones and are leavened with salt. Eight women sit around a table in a room off the foyer. One of them is his mother, Widad. She and the others talk and laugh and roll out date cookies for the birthday of one of her 37 grandchildren. She first says she has 34, but then counts and corrects herself.

Widad saw Pope Paul VI in 1964. She saw Pope John Paul II in 2000, and she and the local nuns will attend Benedict’s Mass today in the Amman stadium.

She rolls, hands sticky with dough, faint with flour. Her husband, the former priest and her first cousin, Sulaiman, was 96 when he died. Around her, rolling cookies, are the family and voices they created to watch over the land.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.