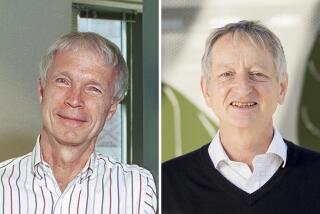

Two U.S. professors share Nobel prize

Two Americans on Monday won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for their seminal work on how people and organizations make decisions and cooperate outside traditional markets -- a growing area of research that scholars said was relevant to such pressing issues as climate change and the behavior of financial institutions.

Elinor Ostrom, a Los Angeles native who teaches at Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind., became the first woman to win the prize for economics since it was first awarded 40 years ago.

She will share the $1.4-million award with Oliver E. Williamson, a professor at UC Berkeley. Ostrom and Williamson were cited for their research beginning in the early 1970s that helped to expand economics beyond the conventional analysis of market prices. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said the pair established economic governance as a field of study that had “greatly enhanced our understanding of non-market institutions.”

Ostrom, who received a doctorate in political science from UCLA in 1965, demonstrated how common natural resources such as pastures, woods and lakes could be successfully managed by user associations and other arrangements outside of government.

She “has challenged the conventional wisdom that common property is poorly managed and should be either regulated by central authorities or privatized,” the Nobel economics committee said.

The panel said Ostrom based her conclusion on case studies, including her own fieldwork that began with her doctoral dissertation that studied institutional entrepreneurship and saltwater intrusion into a groundwater basin under the Los Angeles area.

She has conducted laboratory experiments and made use of other case studies, including research on grasslands in Mongolia that showed how nomad-dominated territories were better preserved by group-based governance than neighboring lands in Russia and China under central rule.

Ostrom said Monday that she was “very surprised” to be awakened at 6:30 a.m. by the news. Before her, 62 men had received the economics prize.

“If you have lived through the era that I’ve lived through, getting into graduate school was a challenge,” she said at a news conference at Indiana University. “You can’t have received a PhD in 1965 and not be deeply aware. The advice to me when I applied to graduate school was, ‘Well, you’ve got a professional job. . . . Why would you try for a PhD? You can’t possibly get a job doing anything but teaching in a city college.’ ”

Although Ostrom is a political scientist by training, her fieldwork and research have the earmarks of an anthropologist and a behavioral economist. She and her husband, Vincent Ostrom, founded Indiana University’s Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. She is also a professor in the university’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs.

In a phone interview, Ostrom said her research suggested that solutions and actions on problems such as global warming could be found at multiple levels. She said decisions by local governments, or even an individual community that built a bicycle path, could make a difference.

“The lesson is that no single level is the only level,” said Ostrom, who graduated from Beverly Hills High School.

Ostrom said she was familiar with Williamson’s work and had attended meetings with him but that they had never written anything together.

Williamson, who was born in Superior, Wis., and received a doctorate in economics from Carnegie Mellon University in 1963, has long been considered a leading researcher of economic institutions, particularly what’s known as the boundaries of the firm.

The committee noted that his research offered insights into conflict resolutions at businesses and other organizations.

Among his contributions, Williamson advanced the thinking into why firms decide to outsource instead of building the operation in-house. His work also helped to explain how firms are different from markets, and why businesses might seek a merger to drive efficiency, and not necessarily to acquire market power -- a point that analysts said had influenced the government’s thinking on antitrust policies.

Scholars said Williamson looked at institutions and their activities from the perspective of transactions, which has been applied in the analysis of other social sciences including law and politics.

“Before Williamson, you had markets,” said Pablo Spiller, a colleague at UC Berkeley. “After Williamson, you have transactions . . . how parts enter into transactions, how and why, and what are the hazards and risks parties are taking in them.”

Roger Myerson, a University of Chicago economics professor and a 2007 economics Nobel laureate, recalled how reading Williamson’s book on economic organizations in 1991 before a visit to Moscow helped him to better understand the nature of organizations and the comparative systems of communism and capitalism.

He said Williamson’s research, although not focused on financial institutions, was relevant to the economic question of the day: how to understand the organization of firms and regulation of their behavior so as to avert another financial crisis.

“The theory of the firm is going to be more essential in the future,” Myerson said. He added that it was striking that the Nobel judges linked Ostrom’s work with that of Williamson’s, finding that both shed light on the nature of trust in economic activity and the effects of regulation.

“I think the Nobel prize committee . . . [is] laying out for the public a statement of what’s important in economics,” he said.

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.