‘The blame must be shared’: Many Blacks fear police are the enemy

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. Please note: Our standards on certain terms have changed, but we have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

There is a well-established rule of caution in the black community that says: If you are black, any contact with the police can unexpectedly become deadly.

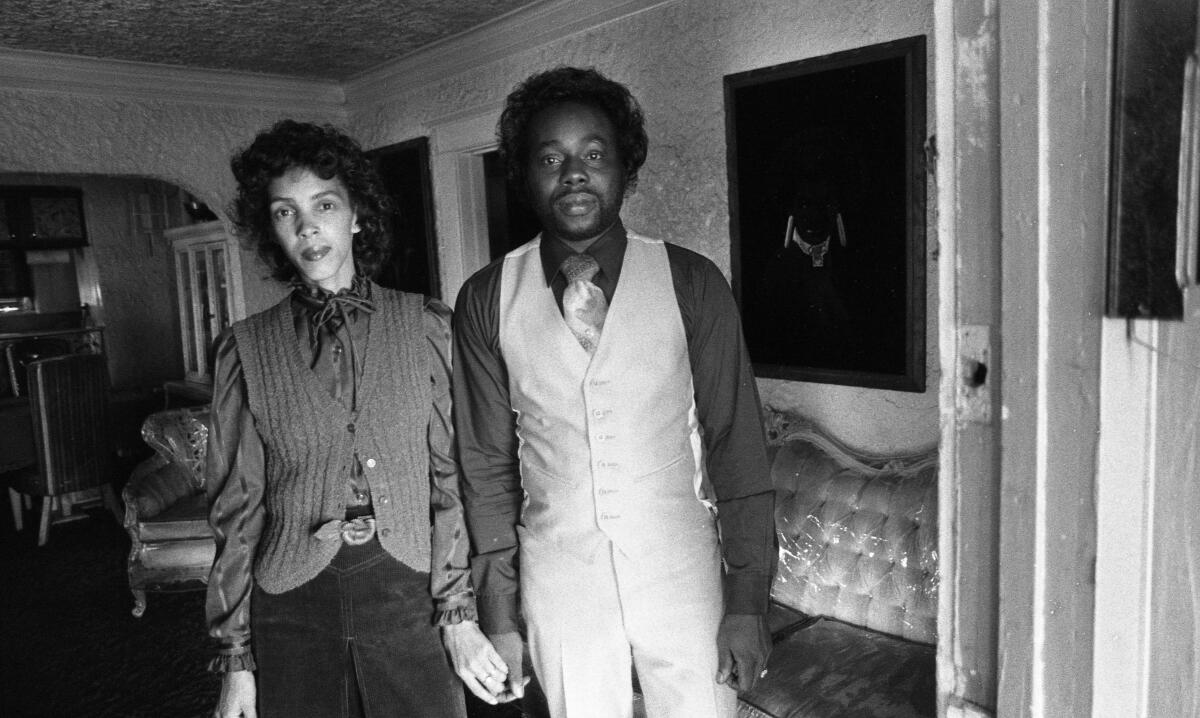

To Udell Carroll, what happened to him one night last February best illustrates that fear.

Carroll, 36, an insurance salesman, pulled into the driveway of his home near 63rd Street and Crenshaw Boulevard after a brief ride through the neighborhood in search of his 16-year-old son. Carroll thought that the boy was out later than he should be; in fact, the boy was already home.

Inside the three-bedroom house, family and friends were chatting amiably. His two youngest children were asleep in the back bedroom.

As Carroll got out of the car, he noticed two policemen behind him. Suspecting he was a burglar, they had followed him. They ordered him to put his hands up.

Carroll said he was confused but careful not to antagonize them. He said he raised his hands and then asked, “What’s this all about?”

In the moments that followed, the scene turned violent. Carroll suffered a nasty head wound that required 18 stitches to close. Forced from the house, his family and friends stood shivering in the cold night air as police cars surrounded the house and a helicopter hovered overhead.

The children watched in terror as white men in blue uniforms, guns drawn, dragged their father and their 16-year-old brother away in handcuffs.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

Black people will tell you it can happen fast. In the blink of an eye, a peaceful evening is transformed into a nightmare of pain, violence, humiliation — and sometimes death.

Of course, there are two sides to every story. And in this story the police version — essentially that Carroll swung first — differs from that of his family. But to disillusioned blacks inclined to doubt the police side of any story, the question becomes: Why is the police version always right and the version told by the Udell Carrolls always wrong?

Harsh as it may be, that question reflects a disconcerting feeling shared by many blacks: Whether they are Beverly Hills lawyers, office workers or welfare mothers, whether home is Watts, West Hollywood or Woodland Hills, the police are the enemy.

That is a perception that casts police as symbols of white power, white racism and white repression. And it leaves blacks with the bitter belief that the police regard virtually every black person as a criminal.

Sociologist Albert Reiss lent support to this belief in a study of the nation’s police departments after the riots that plagued urban America in 1967. Reiss reported that three-fourths of police in predominantly black areas were “highly prejudiced toward blacks. What do I mean by highly prejudiced? I mean they describe Negroes in terms that are non-human terms. They describe them in terms of the animal kingdom.”

Fifteen years later, not much has changed, some would argue.

Last year, retired Deputy Police Chief Louis J. Reiter, who headed the police review board that investigates allegations of police abuse, said officers in one predominantly black area “have developed the philosophy that everybody who is black is a bad guy, and the only way to [police the community] is to be a hard-charging street army, to show them who is boss. And as a consequence, their tactics are terrible most of the time and the shootings we get show that the tactics are terrible most of the time because they are running it like [police] are king of the street.”

Episodes like the following are cited as examples of what can happen:

— Roosevelt Dorn, now a Juvenile Court judge in Inglewood, said he was roughed up by two police officers who stopped him during a robbery investigation and did not take the time to ask him why he was carrying a gun. He was a deputy sheriff at the time.

— Rep. Mervin Dymally (D-Los Angeles), then a state senator, said he was clubbed at a demonstration by a police officer who the congressman said refused to listen to his attempts to identify himself.

— John Brewer, son of Deputy Chief Jesse Brewer, the highest-ranking black in the Police Department, was forced to lie spread-eagle on the ground after a traffic stop.

— Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., then an assistant district attorney, said he was forced out of his car at gunpoint and ordered to put his hands above his head as his two crying children watched fearfully from the back seat. Cochran said the officers told him they stopped him because they believed the Rolls-Royce he was driving was stolen.

These, it could be argued, are the fortunate ones, possessing State Bar cards and other credentials that normally assure safe passage.

But most do not. For every Johnnie Cochran there are thousands of blacks who cannot afford the legal fees and who do not have access to the media, police brass or politicians who can call attention to their complaints.

And when people from this relatively powerless segment of the black community are the victims of improper police behavior, the street encounter is not necessarily the end of it.

They may be hauled off to jail or find themselves in the hospital, losing time from work and suffering disruptions in their family life.

Thus, too many blacks believe that the Los Angeles Police Department motto, “To Protect and to Serve,” proudly displayed on the side of each patrol car, is not for them, and some will avoid contact with police even when their services are desperately needed.

Dr. Howard K. Mason is the psychiatrist in charge of crisis evaluation at the Augustus F. Hawkins Comprehensive Mental Health Clinic. He said he has encountered mothers who refuse to take their distraught children to the clinic if, because of the hospital’s shortage of transportation, they have to be taken there by law enforcement officers.

“They say they are afraid,” Mason said. “They say, ‘No, no, no. They’ll beat my baby. They’ll beat my baby.’”

The sad irony is that blacks suffer disproportionately from crime and want police protection, a point they have made repeatedly by their generally strong support of police legislation at the polls.

Yet, many blacks view the police unfavorably. In a Times poll of 522 blacks, 216 Latinos and 701 whites in Los Angeles, blacks were the only group in which less than a majority had a favorable impression of the police. Forty-five percent of blacks had a favorable impression of police, while 46% had an unfavorable impression. The unfavorable rating jumped to 58% among blacks aged 18 to 44, the bulk of the population.

In that lies a frustrating dilemma. Blacks desire and need police protection but are often fearful of those sworn to protect them.

It is telling that black newcomers to Los Angeles often receive a friendly warning from those already living here: “If you’re stopped, never make a sudden move, put your hands on the steering wheel, stop in a lighted area and never talk back.”

So firmly is this understood that when comedian Richard Pryor, pretending he is a black motorist stopped by the police, haltingly tells the officer, “I ... am ... reaching ... into ... my ... pocket ... for ... my ... wallet. I don’t want to be no ‘accident,’” the audience breaks into thunderous laughter. There is no need to explain the punchline to blacks.

Black critics of police practices believe the evidence supporting their complaints is painfully clear. Blacks in Los Angeles, though only 18% of the city’s population, are twice as likely to be shot by police as whites, police statistics show. Blacks file a disproportionate share of the police abuse complaints received each year by civil rights groups and legal agencies for the poor.

Nationally, blacks make 12% of the population, but they are nine times as likely to be the victim of officers’ bullets as whites. In the 57 largest cities, blacks account for nearly 60% of all deaths by police, according to recent studies.

Law-enforcement officials say this happens because blacks are involved in more violent crimes, thus raising the odds that such incidents will occur. But even allowing for that, the rate of police-caused deaths of blacks appears higher than could be expected.

Los Angeles police statistics show that blacks make up about 36% of all those arrested in the city and about 45% of those arrested for serious crimes. But blacks are the victims of 51% of the shooting deaths involving police and 75% of the chokehold deaths.

But this argument, in a sense, is far from the heart of the matter. The kinds of incidents that disturb blacks frequently have nothing to do with the commission of violent crimes.

Small encounters escalate

They are more often episodes like that described by Carroll, small encounters that, many blacks would argue, escalate into something worse for no apparent reason other than race.

Carroll said the two officers — one male, the other female — who stopped him in his backyard were in no mood to explain their actions.

“‘Shut the ... up, nigger,’” the male officer said, according to Carroll.

“Listen, I’m a man,” Carroll said he responded. “I’m in my own backyard, you don’t have to talk to me like that,” Then, said Carroll, the officer struck him in the face with his fist.

Carroll said he grabbed the officer and pulled him toward the back door of the house, using him as shield against the female officer, who was hitting him in the head with her nightstick. Carroll’s wife said she heard her husband’s calls for help and she called the police.

At the back door, Carroll said, he managed to break free and lock the officers outside. He went to the telephone and told his story to the police at the 77th Division station. His version of what happened, recorded on tape by the police, has not changed.

Father, son arrested

The police officers said they acted in self-defense. They said that after asking Carroll to put his hands up, he began using profanity, resisted a pat-down search and struck the male officer in the stomach.

Carroll was arrested and charged with felony assault with intent to commit great bodily injury. His son, who intervened during the scuffle, was charged with assault and interfering with a police officer in performance of duty. The charges are pending.

There was no loss of life in that episode. But other seemingly small encounters between police and blacks have led to deaths that are not quickly forgotten in the black community:

Eulia Love — shot dead in a 1979 incident that began over an unpaid gas bill. James Thomas Mincey Jr. — dead in 1982 after a chokehold was applied during a traffic stop. Phillip Eric John — shot and killed in 1972 in his apartment by Los Angeles and Inglewood police after he awoke with a start as two detectives stood over his bed with their guns drawn. John was the wrong suspect. Leonard Deadwyler — accidentally shot and killed in 1966 by an officer who stopped his speeding car as he was racing his pregnant wife to the hospital.

Black critics of police believe that these tragic incidents continue because, as Reiter put it, top law-enforcement officials are reluctant to say to their officers, “‘Hey wait a minute, damn it, there are some good people down there.’” Instead, said Reiter, the attitude is one of “‘Don’t upset the troops: they’re out there fighting wars.’”

‘Police are more wary’

But Police Chief Daryl Gates said: “How can I explain how you tell the good from the bad? There is no way. Police are more wary [in the black community] because there’s more violence. ... They are more wary because unfortunately some of the people we’ve put through the academy have never come in contact with blacks.”

There is an even larger question. The conduct of police officers, it has been argued, is ultimately a reflection of the community’s attitude. As the Kerner Commission studying police abuse of blacks in 1967 concluded: “The blame must be shared by the total community.”

And what has been the community attitude in Los Angeles? The discouraging answer, some blacks argue, can be seen in the way the community, through the courts, has sent signals of approval to the law-enforcement community.

In the last four years, only one officer has been convicted by a jury in 23 beating and shooting cases filed against police officers by the district attorney’s special investigative unit. Yet the same attorneys, bringing the same level of experience, have won convictions against officers in more than 50 cases involving burglary, robbery and other offenses — a 95% conviction rate in these cases over the same period.

Said Gil Garcetti, assistant district attorney in charge of such cases: “Believe me, I feel very frustrated about what is happening. The jury is going to identify with and sympathize with the clean-cut officer. I’m convinced that they (the police) have committed the acts they are charged with.”

‘Disrespect for all’

The long-term effect of this on future generations is not known. Lewis King, human development specialist at the Fanon Center, a research institute, said that in some cases a belligerent attitude toward all authority will result.

When parents lose respect for law-enforcement agencies, so do their children, King said. That attitude can develop into “disrespect for all authority, because the traditional symbols of power, the police, the innkeepers of the law and order, are themselves violators of the law and order.”

For now, there is the anxiety of people like Melrose Sprague, a 38-year-old black mother who recently sent this letter to The Times.

“Within two years of my arrival to Southern California, I had three unpleasant encounters with the Los Angeles Police Department, which has left me with a morbid fear of them.

“The worst incident happened one and a half blocks from my home. Alone and en route home, well within the speed limit and obeying all traffic regulations, I saw a flashing red light behind me. I pulled over not the least bit concerned although I was puzzled as to why I was being stopped. I had my driver’s license, a current registration and no broken windshield or dark headlight.

“Turning to my left to face the officer I looked right down the barrel of his service revolver. I shudder to think what might have happened if I had screamed or moved unexpectedly. Upon looking at [my driver’s license] and seeing my home address, one in the $100,000 and up residential area, he put away his revolver.

“His reason for stopping me? I looked like a teenager out after curfew. A LAPD officer suspects a black teenager of being out after curfew so he approaches them with his gun drawn? Where is the logic?

“I have a 17-year-old son. He doesn’t smoke or do drugs and has never been in trouble. He’s a “B” student and star athlete. He graduates next month and has a full basketball scholarship to a Pac-10 college. He’s an excellent defensive driver and a pride to his family. Yet I worry every time he’s out alone.

“I don’t fear that he’ll have an accident or dispute with another person. My major concern is that he may one day be stopped by Los Angeles’ finest. I have repeatedly warned him to keep his mouth shut if he is ever stopped. And for God’s sake, don’t ask why.

“Will they have to use a chokehold on him because they feel threatened? Or worse, maybe he has a suicidal tendency and may hang himself in jail.

“I wonder, how many black mothers share [that] fear.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.