Q&A: How Glory Edim found her voice in her anthology ‘Well-read Black Girl’

Although Glory Edim submersed herself in books since childhood, it wasn’t until she published her first book that she began to accept herself as more than just a reader. Because of the popularity of her Brooklyn-based book club-turned literary festival, Edim was asked to publish a book of her own.

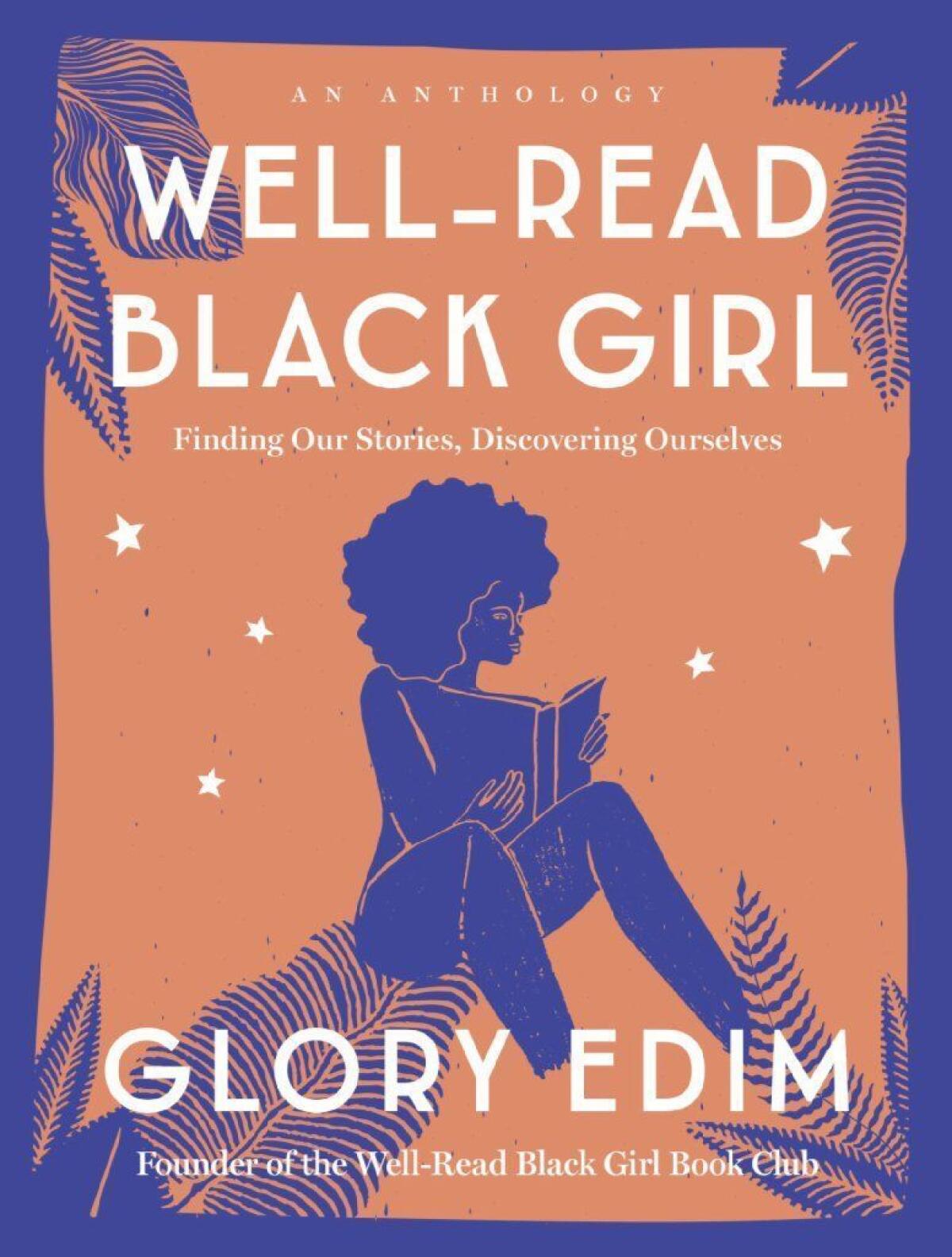

Edim, who was The Times’ 2017 Innovator’s Award recipient, opted to curate an anthology, “Well-Read Black Girl: Finding Our Stories, Discovering Ourselves,” in which she recruited black authors, including Jacqueline Woodson, Morgan Jerkins, Gabourey Sidibe, Jesmyn Ward and several others, to share when they first saw themselves in literature. As the authors unpacked their literary memories in the book, they also unleashed vulnerable stories of race, sexuality and self-definition. In turn, Edim says their openness allowed her to share her story in a way she hadn’t before.

Edim recently spoke with The Times by phone about how she’s embraced her new title as a writer and how the book has furthered her mission to redefine the literary industry. Our conversation has been edited for length.

You started the book with Lucille Clifton’s poem, “won’t you celebrate with me.” Why did you use it, and what does it mean to you?

There’s so much to be said about Lucille Clifton. She is such a dynamic force and literary titan. That poem, for me, spoke to the demand to be seen, to be visible in the work, to be taken seriously and not be compared to anyone else; simply be seen for who you are. I just love the power in her voice. Renée Watson, one of the [anthology] contributors, talks about Lucille’s work about how, being able to be physically seen, Lucille changed her idea of who she was and how she could become a poet, and I felt the same thing reading her poem. It really helped me define who I am. The word “celebration” is not a polite question, it is a demand. Won’t you celebrate me? You have no choice [but] to. Her poems have always stood out to me because it doesn’t feel like a question, it really feels like a declaration.

You were approached by a publishing company to write your own book, and I read that you’ve always thought of yourself more as just a book lover. When did you learn that you weren’t just a reader, but also a writer?

I would say I became fully embodied in myself as a writer and an editor this year. It’s been such a huge learning experience working with the women I admire. 2018 was such a year of becoming for me and feeling powerful and inspired by the contributors. Reading their work allowed me to find my voice and feel confident in telling my story. I oftentimes feel like the community and the books serve as a mirror for me. As I look at the community and I hear the feedback and I get the support, it really does fill me with such confidence and joy that I can do it because the community has trusted me.

You’ve come to terms with calling yourself a writer this year?

I feel like I’ve always been a storyteller, but coming into my own as a writer is still happening. It’s really exciting to build something and be a part of helping others expand the publishing industry and give writers a boost who may be overlooked or who feel marginalized. I also know that I am still learning as I even claim the word “writer” in its truest sense. I have my own insecurities around things. I studied journalism, but I don’t have an MFA. I didn’t go to Iowa, the legendary school, so I’m coming into this world with the thing that we all have, my own story, and I’m trying to stay true and authentic to that.

You are also working on a memoir. Have you started writing?

I have a solid draft of what I’d like to share, [but] I’m trying to find the narrative in how I want to tell my own story. It’s interesting because I’m used to reading everyone else’s story [laughs]. I’m used to having myself buried in a book. Reading memoirs and short stories are like two of my favorite things to sit down with. So now that I’m writing my own, I have to really have clarity in what I want to share with the world and why I want to share it. How this can help other people and also help my own personal healing? I’m discussing some traumatic things that happened, some triumphs, some challenges, but also the joy that has happened in my life too and the love that exists in my life. Most of the story is between my mother and I. As I’ve shared before, my mother was severely depressed, and writing about mental illness can resurface painful memories, but I’m in a good place now where I’m able to confront it and share it, and do so without shame. As I was reading my old journals from when I was younger, I was like ‘Oh, wow.’ There was a lot of fear in what I was writing. There was a lot of shame or resentment, and now as an adult, I’m writing from the perspective of what can I tell my younger self and what can I share with the black community in particular about understanding the complexities of mental illness and family and that dynamic. It’s been wonderful to just even have the space. I really want to do my best to honor my mother’s story, my father’s story and my own.

So, you’ve been referencing your journals for the memoir. How long have you been journaling?

I have journals from when I was 8 years old. I mean, some of them are not as concise and are just entries [laughs], but I’ve been writing for a really long time. In particular, during the time when I was in college that was a really important moment for me because I was constantly writing things down. I’d always ask this really random question like how should you be as a person? What does it mean to be an adult? When I was in college, I was trying to figure out what does adulthood look like? I was trying to figure out who I was as a woman.

Going back to the anthology, what type of questions did you ask the contributors?

I posed the question, “When did you first see yourself in literature?” but what happened was, that question became an unpacking of literary memories and reflections and all the stories really answered the question of self-definition. When did you define yourself? When did you give yourself permission to become a writer? That is what I saw in each essay. It really was about this is when I said, “I am a writer” and pronounce it proudly. And then also there was an interrogation of the text like when Tayari Jones was talking about reading “Tar Baby” as a young person and then reading it as an adult like she is challenging her work and challenging herself to understand her story in a more and intimate way.

Speaking of vulnerability, some of the contributors shared some very personal stories, including Dhonielle Clayton’s piece about understanding her sexuality and Gabourey Sidibe’s about her family issues. How was it for you reading these pieces?

I was so honored that they would share these heartfelt moments with me, and it crystallized the importance of telling your own story because everyone is like deeply personal in the essays. It really gave me the confidence to share my own story. I just think overall “Well-Read Black Girl” is complex and it’s unforgettable. After you’ve read this book, you’re not going to forget who Nicole Dennis-Benn or Tayari Jones or Lynn Nottage are because now you know that there’s beginnings in their stories. I think right now we’re engaged in politics and aesthetics that ask what is black literature? Who are these voices that need to be heard? I think it’s important for us to clarify the “we” that we’re talking about. The “we” goes across the diaspora and its about being dynamic and globally focused and really making connections between the movement of black Americans in the rural south to the northwest to L.A. It’s finding the connections of all of our stories and making a space where a reader can really engage with what’s important whether it’s artistic or political, and continuing to build social conversations. That’s what feels like a movement to me. [It’s] where we’re having conversation that are really cultivating our voices, and I’m proud to be able to promote the community and support for writers of color, specifically black women and that is something that I personally feel is happening all over, especially online.

A quote from the book that people seemed to connect to on social media is: “My biggest responsibility is to recognize that I am part of a continuum, that I didn’t just appear and start writing stuff down,” by Jacqueline Woodson. That’s kind of what your anthology feels like.

For me, it was about working in tandem with all these amazing women that really fed me as a young person and helped me cultivate my own voice, and I really do feel that I’m part of a legacy and lineage of incredible black women writers from Toni Morrison to Alice Walker. These are all women I incredibly admire, and I want to pay tribute to their work. I really feel like “Well-Read Black Girl” has changed my life, and it’s welcomed so many new friendships and lifelong relationships into my life, and I’m really proud of it, but I will always be [a part of] the community, and the anthology is a tribute to storytelling and sisterhood. I always say that I’m not the first or the last to do this work. Black women have always been at the forefront of community, and I’m just adding my story to it, and I’m listening and I’m constantly looking to be an advocate for women for black women. I want to be a person that can encourage other people and support the work of other women, as they are reciprocal and do the same thing for me. When you come to “Well-Read Black Girl,” you’re going to always find affirming and a positive outlook on who we are and that isn’t without intellectual pursuit and a dedication to craftsmanship. All of that is included. It’s a whole complex person. That’s what I’m trying to share with the work that I do. [To show] the complexity and the beauty of black women and our stories.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.