Daniel Clowes is looking for a role model in comics (sort of)

- Share via

Daniel Clowes is not a man of science. His comics might step into the speculative and unknown, and sometimes time travel or death rays figure in his human dramas of the hilarious and the horrible, but he hasn’t exactly got this stuff figured out.

His 11-year-old son, Charlie, however, is obsessed with quantum physics and computers.

“Luckily he can’t read my books because it’s got too much swearing,” Clowes says with a laugh. “But when he does in a year or two, he’s going to be appalled by the science.”

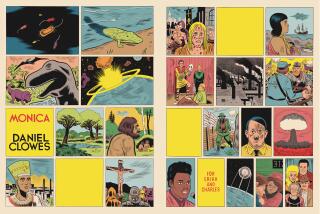

In his new book, “Patience,” time travel is merely a plot device to get to larger themes as an angry man deep into middle age discovers a means to possibly prevent the tragedy that ruined his life — or to at least punish the villain who murdered his pregnant wife years before.

The story — his longest, at 180 pages — follows the desperate journey of a bitter and broken Jack Barlow into the imperfect past. It’s told with Clowes’ usual biting humor, vivid renderings of plausibly bizarre behavior and his protagonist’s sudden eruptions of rage. There are also deeply moving moments as the graphic novel slowly unveils the troubled youth of the doomed title character Patience, leading to an emotional denouement in Clowes’ final panels.

“When I was a teenager,” he says, “I used to think about what would you do if you had time travel? What would you do if you had superpowers? If you really play it out, it’s a difficult proposition. You’d probably just keep it to yourself.”

The book was initially inspired by the experience of self-examination as he prepared his work for the “Modern Cartoonist: The Art of Daniel Clowes” exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California in 2012 and its accompanying book, followed by a slipcase collection of his “Eightball” anthology comic.

“Doing the third thing, it was ‘OK, I’m so sick of my 28-year-old self,’ ” says Clowes, now 54. “I felt really alienated from that person, so it was about this old man looking at this young person and examining him with ruthless clarity but also finding some sympathy for that person.”

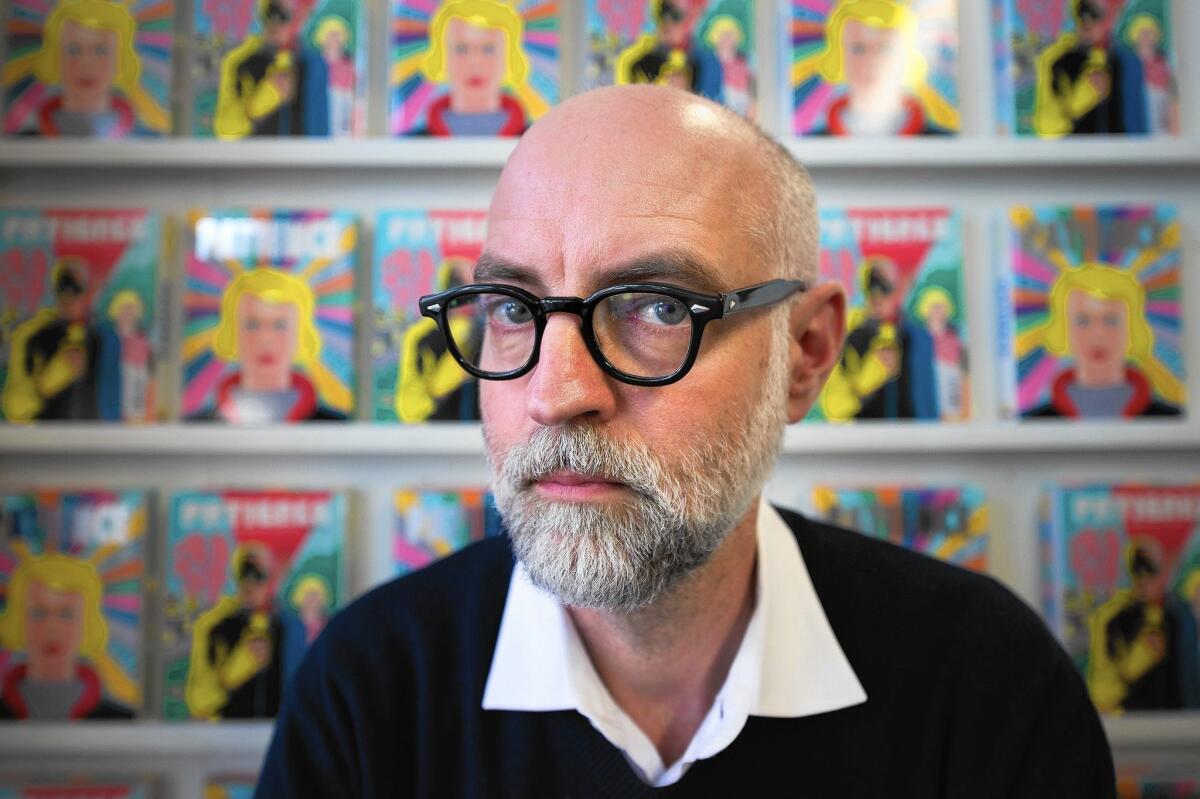

Clowes, who lives in Oakland, is gray-bearded and in a black pullover sweater as he drinks ginger beer in a hotel lobby bar on the Sunset Strip. Just outside, sunbathers relax by the pool. In an hour, he’ll leave for a signing at Meltdown Comics, a store he calls “one of a kind.”

Years ago, when he was a young comics creator known only to a select crowd of fans, Clowes created the store’s one-eyed alien boy logo, and he’s kept a close relationship ever since. When an animated version of Clowes appeared on “The Simpsons” (alongside fellow comics creators Alan Moore and Art Spiegelman) in 2007, it was at a store called Coolsville that was clearly a parody of Meltdown. Inside the real store on Sunset is a display case of Clowes memorabilia, including dolls of the irritable teenage girl Enid, the central character from “Ghost World,” his 1997 breakthrough work that helped usher in a larger audience for literate alternative comics.

His generation of comics creators built on the legacy of work by the underground revolutionaries of Zap Comix, Raw and other titles drawn by the likes of Spiegelman, Robert Crumb and Robert Williams. The audience has evolved too. In the alternative 1990s, Clowes and his indie comics brethren could easily identify their readers in a crowd of comic convention attendees.

“I felt like we knew every reader by name,” Clowes says of those days. “We acted very cool: ‘Oh, yes, we get many fans,’ but we knew. This was pre-Internet. To do a book and have a response from a hundred people was incredible. Now people post a picture of their lunch and get 200 responses. It’s a very different thing.”

Clowes also senses a change in himself. The layers of feeling in “Patience,” he says, reflect his experiences as a family man with a different view of what is at stake in life. It began with the birth of his son.

“Before I had kids, I sort of had the vantage of a surly teenager. Even when I was 30, I still was that,” he says, “and I have a lot of friends who are 60 who are still that, basically. Then all of a sudden I became ‘I’m the voice of authority. I’m the dad,’ and all that entails, and the terror you have to face with that.”

He once imagined a time when his sophistication as an artist and storyteller would become so advanced and refined that his work would become effortlessly shorter and concise. He always saw himself as an author mainly of shorter works, but “Patience” kept growing.

“You’d read about these old comics guys who would learn little techniques that would pare it down to the essentials,” Clowes says. “That was always my dream, and it just gets slower and slower. Everything is more labor intensive than it used to be.”

For the new book, he also chose to draw each page on larger 18-by-22-inch boards. He started the book in 2010, beginning by “figuring out the moments, the beats,” then imaging the story unfolding in two-page spreads, “but keeping it as loose as I could up until the day I was drawing it.”

In the past, he has “over-thought” his work down to the smallest detail. “Then it’s joyless to just draw it. You lose the spontaneity of it. Nothing weird ever appears.”

He worked on many things during the years he labored on “Patience,” including covers for the New Yorker magazine, but spoke little about the book in progress. A friend visiting his home on occasion might get a glance at a page Clowes was working on, but no one read it.

One person who never looked until Clowes was finished was his wife, Erika.

“I need her to have this totally fresh take on it when I’m done, because she’s the only person I totally trust,” he says. “I know she’ll really read it carefully and honestly, so I don’t want to poison it. I don’t tell her anything about it.”

With “Patience” behind him, Clowes has begun thinking of his next big project.

There was a time about a decade ago, following the success of the film version of “Ghost World,” for which he co-wrote the screenplay and was nominated for an Academy Award, when Clowes thought he might veer into scriptwriting. Though he did write the screen adaptation of his own “Wilson,” to be released this fall starring Woody Harrelson and Laura Dern, that feeling has mostly passed.

“After a little while away, I started to feel I should be doing comics,” he says. “That’s the thing I can really do.”

Lately, he’s been contemplating how his work in comics might further evolve with age and wisdom. The closest work he’s seen to reflect another level of comics advancement was Crumb’s version of “The Book of Genesis.”

“I’m sort of looking for a role model,” Clowes explains. “There are role models as filmmakers and authors of this, but not in comics so much. If somebody is in their 70s doing this pure, pared-down versions of what they are — the way John Huston did, where a lifetime of experience is imbued in this later work — I’m looking 20 years ahead to that.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.