L.A. architect David C. Martin’s unusual Mexico travel journal

- Share via

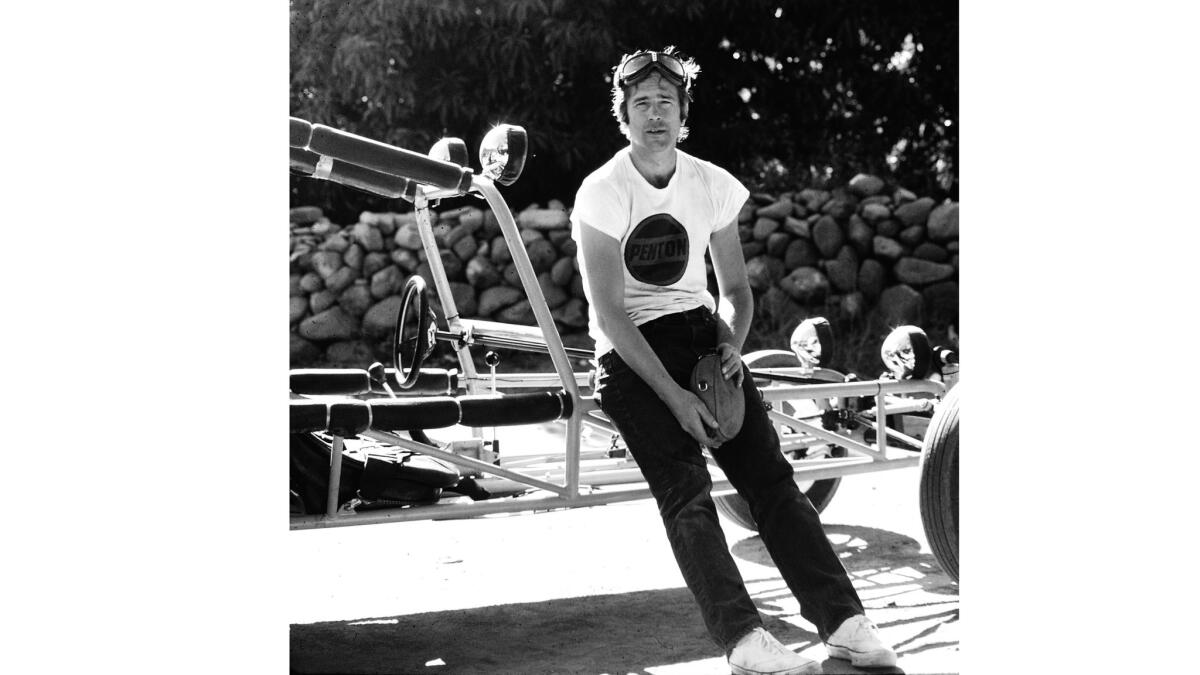

Long before designing the Wilshire Grand Center, better known as the tallest building west of the Mississippi and the pinnacle of the Los Angeles skyline, David C. Martin was an architecture student at USC who spent Friday nights on “architectural joyrides” in a Volkswagen Bug, driving around the city to study Victorians on Bunker Hill or the interiors of Union Station. That sense of exploration and observation stayed with him as he embarked on more far-flung journeys, including numerous visits to Mexico to study missions and plazas, cathedrals, monuments and domes.

“For me, Mexico is familiar and exotic, accessible and out of reach,” he writes in “Joy Ride: An Architect’s Journey to Mexico’s Ancient and Colonial Places” (ORO Editions, $29.95). It’s also a recurring source of inspiration — “design ideas I observed in Baja churches guided me as I created new sacred spaces” — that would inform his work for decades to come.

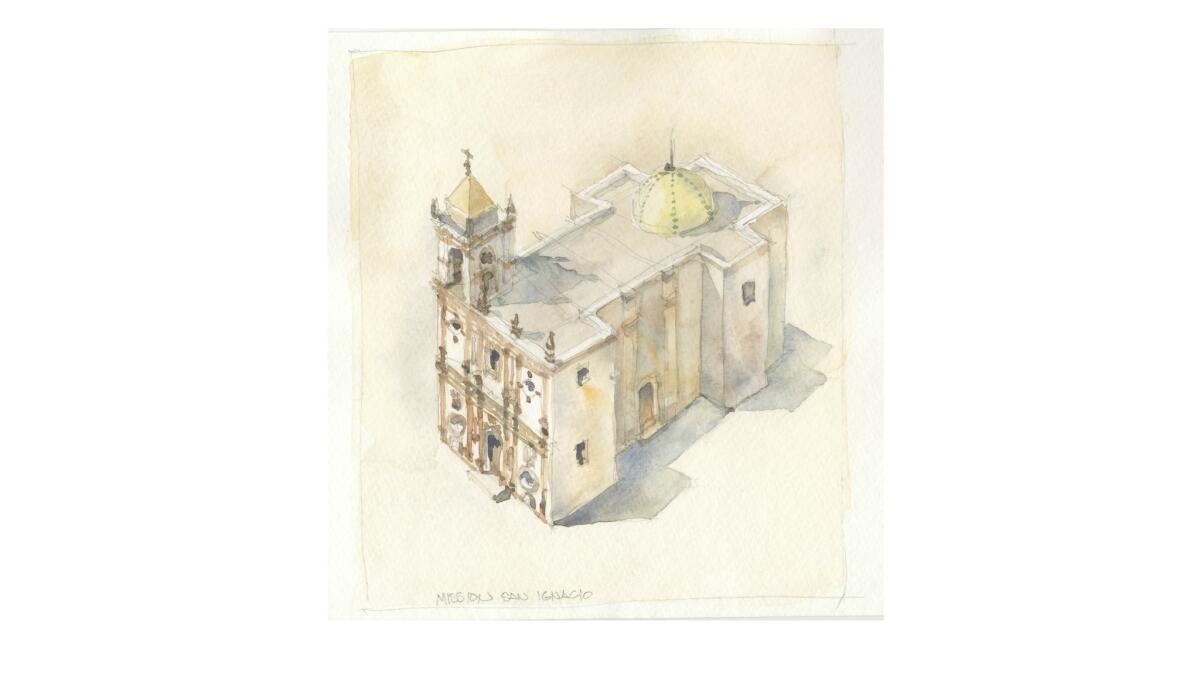

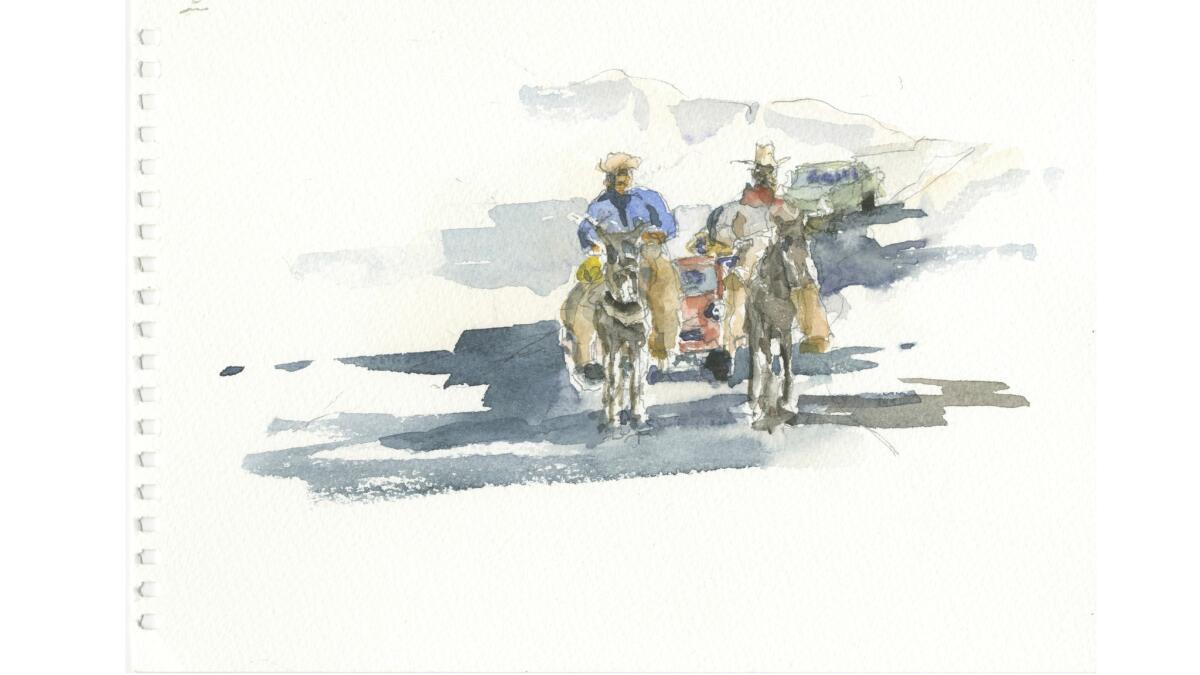

Part notebook, part travelogue, part architectural history and urban planning primer, “Joy Ride” is a visual odyssey, full of sketches, photographs and, most appealing, watercolors made while he was a young man in the 1970s, touring Mexico.

A third-generation architect, Martin was a design principle of AC Martin, his family’s century-old firm. (His grandfather was a collaborator on L.A.’s City Hall.) Already steeped in the architecture of Southern California, Martin sought to immerse himself in an even deeper tradition in Mexico: “centuries of thought-provoking architecture and town planning” that “significantly altered (his) understanding of the history of the American west.”

In “Joy Ride,” Martin recounts both anecdotes of his travels and architectural facts — he races cars in Baja, gets stuck in a river and critiques the Jeffersonian grid — while his drawings of Mexican plazas and missions reveal something more intimate: a creative mind in the throes of absorbing its influences.

“As artists work, they decide to include and emphasize some aspect of a scene while ignoring or eliminating others,” writes Martin. “In the old cities, I found myself continually deciding what mattered to me and what I wished to convey about their message for our future.” His later designs for the Wilshire Grand, or the interfaith chapel at Chapman University, contain echoes of what he deemed essential: function, community, a harmony between the public and private space.

In some sense, “Joy Ride” is a glimpse into the work that an artist does when he’s not exactly working, the many observations that become grist for the mill. “I feel that a painting or a sketch allows the viewer great freedom of imagination,” he writes — in other words, without the burden of perfection, a sketch can be a place to explore. Often, a sketch is a first step, a rough draft, the means to an end. At other times, however, it’s the end in itself, an exercise in experimentation and pleasure, like riffing on a guitar.

“In sketching and making watercolors… I was aware once more that I find these media valuable for what they do not tell us, as well as for the information they do impart,” he writes. Some sketches don’t go any place in particular; they’re joyrides.

David C. Martin reads from the book at 7:30 p.m. Thursday at the Huntington Library.

Correction: 2:40 p.m. Aug. 2: An earlier version of this post said that David C. Martin was a principal at AC Martin. He has retired.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.