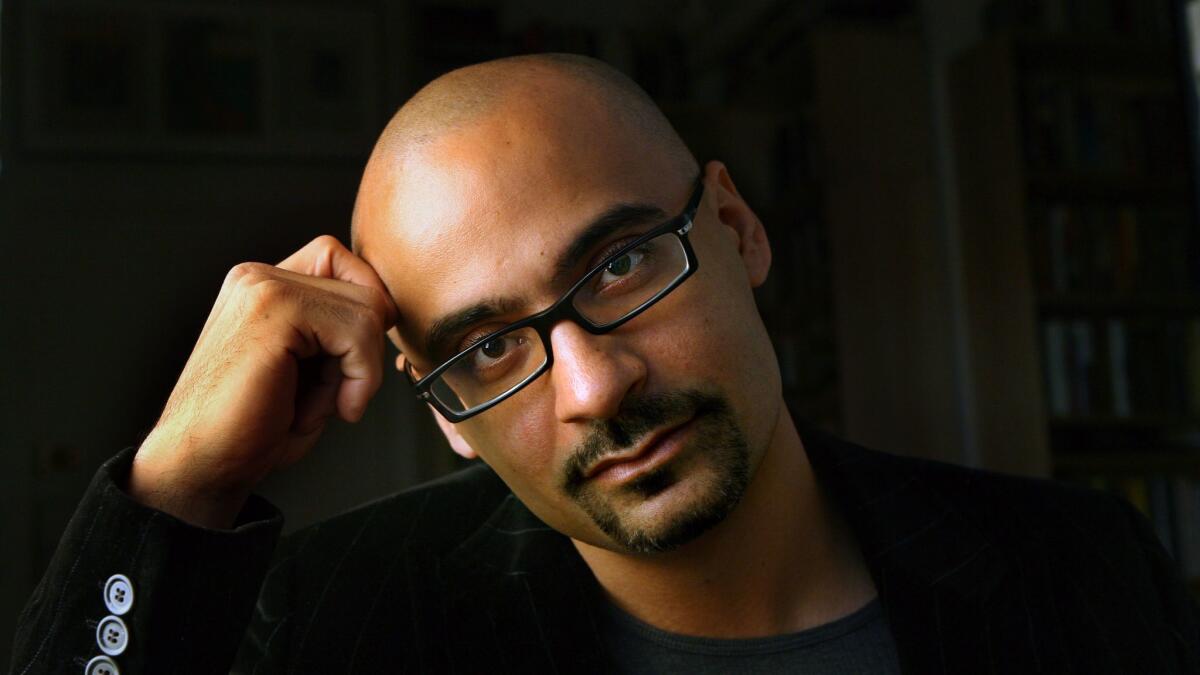

Junot Diaz puts the audience center stage at REDCAT

Moments before Junot Diaz was scheduled to appear at REDCAT, a young woman who braved the storm to wait for a ticket on standby caught sight of the author and asked if he’d sign her copy of “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” After the crowd had shaken off their umbrellas and filed into their seats, Diaz took the stage and called out, “This young sister named Guadalupe. Is she actually here?” She raised her hand, beaming. “I’m glad you made it in,” he said.

Authors typically read before directly engaging the audience, but Diaz, MacArthur “genius” fellow and current Katie Jacobson writer in residence at CalArts, reversed the standard order Friday night and immediately opened with dialogue. There would be no daydreaming through some rote recital for this audience. Diaz, spotlighted and roaming the stage before a dark velvet curtain, invited conversation. He wanted to know, and asked outright, “What y’all thinking about?”

He also asked who in the audience was Latino, Caribbean, Dominican, of African descent. (As in a Junot Diaz story, I overheard a conversation behind me that slipped seamlessly from Spanish to English and back again. “Te pregunta because my battery’s dying,” one woman hoping to snap a “latergram” said.) Diaz welcomed questions from the audience, but made it clear who should take precedence. “Why don’t we first hear from the women of color?” he said.

Most questions sprung from anxieties about the Trump administration — the political responsibility of artists, upholding intersectionality, how to resist. A young woman named Ismaelly Peña asked, as the daughters and sons of immigrants, “How do we speak to our parents about these issues?” She had attended the Women’s March in January, but her mother disapproved. “‘We didn’t bring you from Cuba for you to be marching,’” her mother told Peña, who explained, “I felt sad, honestly, and I didn’t really know how to respond to her…someone who gave up everything for me.”

Diaz nodded sympathetically. “You basically quote my mother,” he said. Throughout the evening he moved along the stage and aisles, closing the distance between himself and whomever he addressed. Despite the packed house, each exchange felt both inclusive and intimate. “What I had to learn was to be compassionate to my mother,” he said, and encouraged Peña to do the same. “That’s why parents have children…it’s so that they can be taught.”

Diaz’s work often addresses the immigrant experience through what he referred to as, simply, “family stories.” As on the page, he is not afraid to be vulnerable. “By the time I was 12 my dad had slapped me around so much I don’t know if I felt anything but slaps,” he said.

Originally scheduled for January, the evening had been postponed to accommodate an invitation to a private lunch with Obama, and Diaz recalled his particular honor at meeting the president. “I kind of like bringing that [younger self] with me to the White House, because there’s nothing wrong with the terror and despair and the sense of being completely unloved that that little guy felt…I need to be able to hold that person next to me.” Still, the experience had been overwhelming. “I ate the crust of the dessert. I didn’t eat anything else,” he joked. “Obama ate everything.”

Diaz is a natural on stage: funny and candid, he moves from loose banter to provocative and inspiring political discourse with ease. (When it came time to read from his novel, he casually borrowed a copy from someone in the front row.) Although Diaz claimed not to possess the same optimism that he’d sensed in Obama, he cautioned against despair and the traps of dystopian thinking. “When we fear that tomorrow will be worse than today, you basically fight to preserve today, which, in a profoundly unequal society, is incredible helpful to hegemonic elites,” he said. “We have to be able to at least be able to imagine better futures if we’re going to be able to realize them.”

His call to action was practical and concrete. “I just keep volunteering…Nothing reminds you of how much agency you have as when you help someone in need. It recalls to you your privilege, which is another word for access to agency.”

Most people stayed afterward to grab a drink at the dimly lit REDCAT lounge, or like Peña, to take a photo with Diaz and have their books signed. An architect, she fell in love with Diaz’s work while living in New York. “It was familiar,” she said. As a writer of the diaspora, she felt Diaz understood. “My parents came to this country for political reasons,” she said, her eyes wet. “It’s a right to voice your opinion…that’s a privilege that they gave me.”

Guadalupe Madrigal, the UCLA student whom Diaz had checked on at the outset, skipped the crush of the signing line. Had it been difficult to get a ticket? Not with a little help: after he’d signed her book, Diaz himself spoke to the venue and got her in. “I’m not gonna forget that,” she said. “Never never.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.