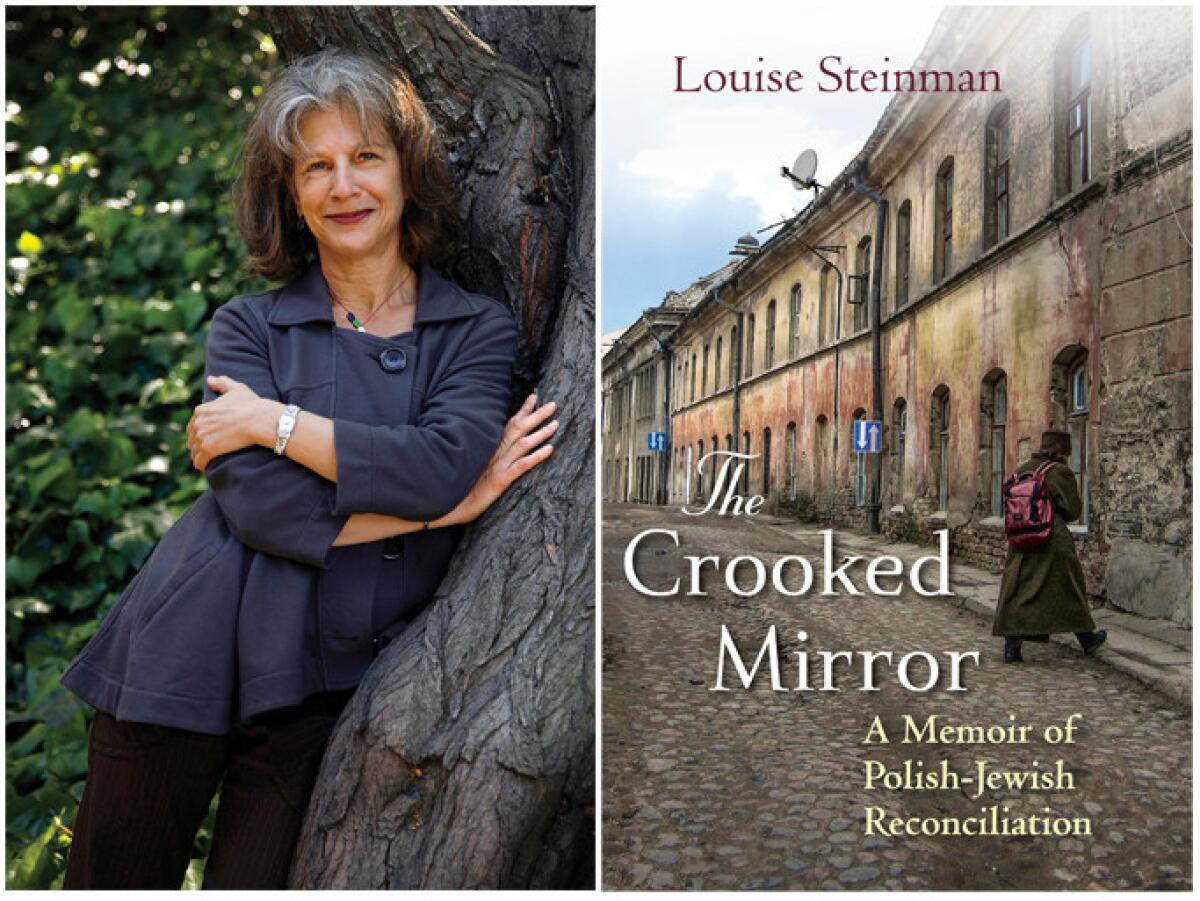

‘The Crooked Mirror’ reflects a Polish-Jewish journey

- Share via

More than 3 million Jews lived in pre-World War II Poland, making up 10% of the population. Today, the Jewish population is at best a tenth of a percent of what it was in 1939. Yet the world is not devoid of Polish Jews. As noted by Louise Steinman in “The Crooked Mirror,” her firsthand report on what remains of Jewish life in contemporary Poland, four out of five American Jews are of Polish-Jewish descent — a diaspora within the diaspora.

Steinman’s previous book, “The Souvenir,” was prompted by her discovery of a Japanese flag among her father’s World War II effects and, among other things, details her subsequent trip to Japan to return this enigmatic trophy. “The Crooked Mirror” recounts a related quest. The author’s maternal grandparents immigrated to the U.S. from Poland, leaving an extended family in the south-central city Radomsko, most of whom perished in the Holocaust. Early in the 21st century, Steinman set off to uncover what remained of her truncated Polish roots and found herself navigating the unresolved psychic residue of the 20th century’s greatest crime in the land where that crime was largely committed.

How do Poles feel about their nation’s vanished Jews and how do Jews feel about the loss of their centuries-old homeland? How should they? Taking its title from that of Der krumlikher shpigel, a satirical Yiddish-language periodical once published in Radomsko, “The Crooked Mirror” begins with a prompt the author received from the “Zen Rabbi of Malibu” to explore the “gnawing void” of Polish-Jewish relations.

Sign up for our email newsletter, “Bookshelf”

Steinman’s first leap into the unknown is a “Bearing Witness” retreat held on the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The experience reduced her to one-word sentences and one-sentence paragraphs: “Breathe in why. Breathe out why. So simple. So difficult.”

The New Age tone is initially off-putting, but once Steinman returns to Poland and starts poking around, her fascination is contagious. The writing improves as well — thanks in part to the introduction of sometime companion and fellow seeker Cheryl, an American-born Polish Jew with a far more traumatic family history. (Having survived the war in a Soviet labor camp, Cheryl’s father was driven out of his hometown Kolomyja — where his family had been massacred — when he attempted to return.)

Cheryl’s ambivalence is disarming, and the vivid dreams she often recounts are blunt as billboards. The women attend a klezmer concert in Krakow. Steinman is troubled by the seeming minstrelsy of Polish actors dressed as Hasidim to sing Yiddish songs; Cheryl dreams that night of watching a performance at the “‘Do You Miss Us?’ Cabaret” where the décor includes vitrines filled with confiscated Jewish belongings. It’s a premonition of the discomfiting trip that, accompanied by Steinman, Cheryl makes to Kolomyja, which because of the postwar shift in Poland’s borders is now in Ukraine.

By then, this reader had come to accept that “The Crooked Mirror” would be a kind of Jungian acid trip full of signs and portents and dreams. (“Poland had insinuated itself into my conscious and unconscious life,” Steinman writes. “I’d even dreamed a map of Poland etched on the palm of my hand.”)

Over the course of her memoir, the author not only consults with various, invariably “wise” historians and other Gandalf figures but a sympathetic Lakota Sioux. Pondering her journey, she lays out the photographs she’s taken “as if they were tarot cards”; back in Los Angeles and unable to sleep, she transports herself to Radomsko via Google Earth. Pondering the mystery of the Seer of Lublin, she even experiences a visitation.

But in the book’s final third, the author (co-director of the Los An¿geles Institute for the Humanites at USC) turns her attention to those Gentile Poles she calls the “Saviors of Atlantis,” individuals who have taken it upon themselves to recover and preserve those vestiges of the Polish-Jewish past that still exist.

“Don’t confuse this with philo-Semitism,” the Polish Jewish journalist Kostek Gebert warns her. “It’s not Jew-specific. It’s Poland-specific.” Soon after, Steinman discovers that, during the German occupation, some of her Radomsko relations had been saved from certain death and sheltered by a Gentile neighbor. And after that she learns the bitter truth that such wartime courage may be as much a stigma as mark of heroism.

Steinman doesn’t much employ the Hebrew term “tikkun olam” (the task of “repairing the world”), but that’s essentially what her book is about. In a touching grace note, “The Crooked Mirror” ends in Radomsko with a public tribute to the son of the first local inhabitant to be publicly identified as a rescuer (and consequently honored as a Righteous Gentile by Yad Vashem). It’s a recognition that, in her innocence and tenacity, Steinman essentially brought about.

Hoberman’s most recent book is “Film After Film: Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema.”

The Crooked Mirror

A Memoir of Polish-Jewish Reconciliation

Louise Steinman

Beacon Press: 224 pp. $26.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.