Column:: How scientists failed the public in the Flint water crisis

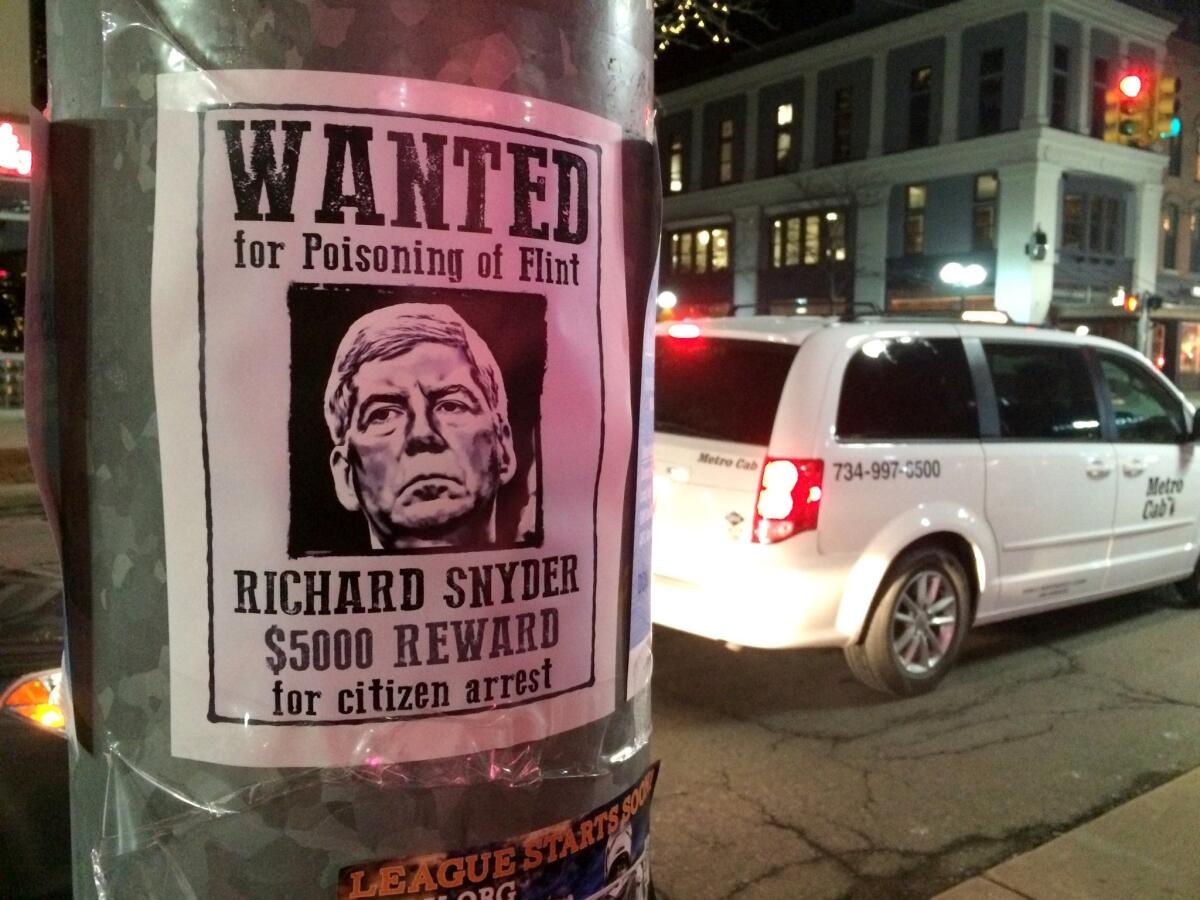

Not the only guilty party: Poster offers a $5,000 reward for “citizen arrest” of Michigan Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, whose officials played a key role in the Flint water crisis. But where were the scientists?

The Flint, Mich., water crisis, in which thousands of children were exposed to elevated lead levels after a supposedly money-saving decision to start using the corrosive Flint River as the city’s water supply, is more than a massive failure of politics and regulation. It’s also a failure of science and scientists.

That’s the opinion of Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech civil engineering professor who helped the Flint community expose the dangers of the changeover last year. Kevin Drum of Mother Jones points us to this blistering interview Edwards has given to the Chronicle of Higher Education, describing how the fundraising culture of academia, even at public universities, discouraged independent scientific study of what community activists and even government researchers saw as a developing health disaster.

The pressures to get funding are just extraordinary...and the idea of science as a public good is being lost.

— Marc Edwards of Virginia Tech

Edwards described the “perverse incentives that are given to young faculty” for the Chronicle’s Steve Kolowich. “The pressures to get funding are just extraordinary. We’re all on this hedonistic treadmill — pursuing funding, pursuing fame, pursuing h-index — and the idea of science as a public good is being lost.” (The h-index is a measurement of a researcher’s prominence, based on citations of his published papers.)

Edwards argues that these incentives drive researchers toward safe projects that won’t risk irritating a potential funding source and away from studies of merely public (as opposed to commercial) interest.

Edwards’ own experience underscores how the process works. He first made his name publicly in 2003 by determining that there was lead in the Washington, D.C., water supply, angering the powers that be in the capital. Vindication came in 2010, when the Centers for Disease Control reversed its long-standing position that the water was safe.

Last April, Leeanne Walters, a Flint mom whose complaints about the water coming out of her tap were getting the cold shoulder from city and state officials, reached out to Edwards after reading an old article about his work in D.C. The lead levels in the water samples she sent him were the highest he had ever seen.

“My heart skipped a couple of beats,” he told the Washington Post. “The last thing I needed in my life was another confrontation with government agencies. But it was us or nobody.”

By then, statistical evidence of a spike in children’s lead levels was inescapable. In part, that was because a Michigan state law required extensive lead testing of preschool kids. Pediatricians had also noticed a spike. The evidence simply went unheeded, dismissed in an atmosphere that elevated the mandate to save public funds by shifting Flint’s water supply from Detroit’s city system to the Flint River.

Edwards contends that the united front of political and regulatory bodies discouraged scientists at public agencies and institutions from aggressively examining the crisis. “In Flint the agencies paid to protect these people weren’t solving the problem,” he says. “They were the problem. What faculty person out there is going to take on their state, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency?”

Good question, considering that the world-caliber University of Michigan has a satellite campus in Flint itself -- sitting atop an underground channel carrying the river. The university as an institution has the clout to get its way, but individual researchers typically are on their own in choosing their projects and finding grants, and they’re wary of challenging public patrons.

That’s troubling, Edwards says, because “if an environmental injustice is occurring, someone in a government agency is not doing their job. Everyone we wanted to partner said ... we want to work with the government. We want to work with the city. And I’m like, You’re living in a fantasy land, because these people are the problem.”

Several threads have become braided together to sap researchers of their spirit of independent inquiry. Although public sources remain significant sources of science funding, their share of total resources has plateaued or declined. That forces researchers increasingly to seek backing from industry, which understandably pursues its own interests, not the public’s. Scientists are discouraged from pursuing nonsexy projects such as double-checking published results, so the all-important process of investigating the reproducibility of previous findings falls by the wayside; the first published results take on an unwarranted aura of authority.

Then there’s the politicization of science research. In Washington, Republicans in Congress have mounted an all-out attack on research related to climate change, which could prompt many would-be researchers to think twice about entering the field.

As it happens, the publicity surrounding the Flint crisis may be opening the floodgates of public funding for scientific studies of the crisis. The University of Michigan-Flint has earmarked $100,000 in “seed money” to launch research into the crisis. But what about a program to proactively fund scientists pursuing the public interest? That doesn’t seem to be on the horizon.

Edwards sees the prospect of greater public funding for research in Flint to be an illustration of the problem, not a remedy. “The expectation is that there’s tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars that are going to be made available by these agencies ... so we now have a financial incentive to get involved. ... But it doesn’t change the fact that, Where were we as academics for all this time before it became financially in our interest to help? Where were we?”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.