F-22 program produces few planes, soaring costs

Delays, technical glitches and huge cost overruns in the Air Force’s F-22 fighter jet program highlight the Pentagon’s broken procurement process.

- Share via

When the U.S. sought to assure Asian allies that it would defend them against potential aggression by North Korea this spring, the Pentagon deployed its top-of-the-line jet fighter, the F-22 Raptor.

But only two of the jets were sent screaming through the skies south of Seoul.

That token show of American force was a stark reminder that the U.S. may have few F-22s to spare. Alarmed by soaring costs, the Defense Department shut down production last year after spending $67.3 billion on just 188 planes — leaving the Air Force to rely mainly on its fleet of 30-year-old conventional fighters.

"People around the world aren't dumb," said House Armed Services Committee Chairman Howard "Buck" McKeon (R-Santa Clarita). "They see what we have. They recognize that our forces have been severely depleted."

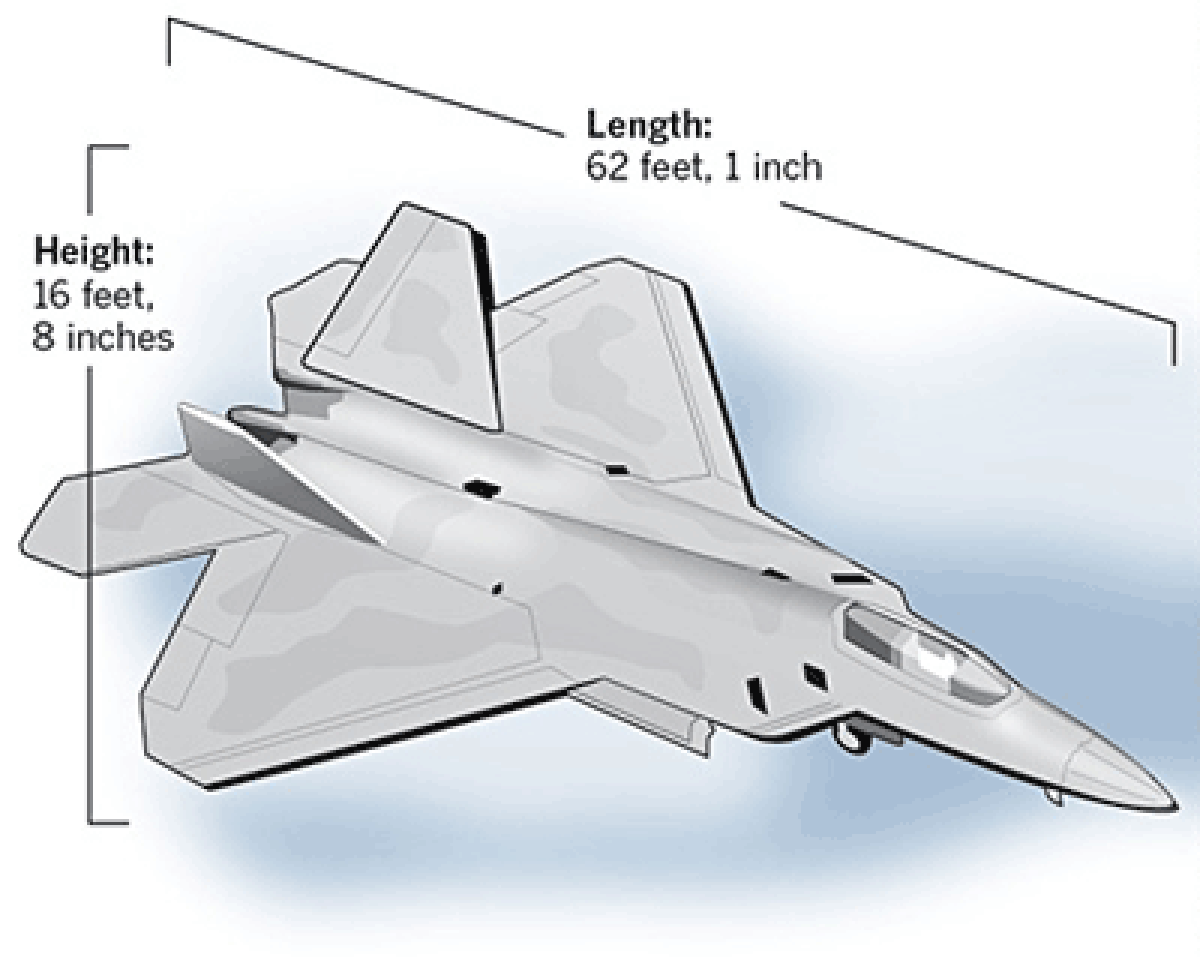

Lockheed Martin Corp.'s F-22 is the most lethal fighter jet in the world. But it has also become a symbol of a broken procurement process that's failing to deliver advanced weapons systems on time, on budget and in sufficient quantities.

The F-22 was originally intended to replace all of the Air Force's F-15 combat jets that date back to the early 1970s. But today those F-15s still represent the bulk of a so-called air superiority fleet — the jets that are supposed to outgun enemy aircraft and gain control of the sky.

Nonetheless, the F-22 program cemented Lockheed's position as the premier manufacturer of combat aircraft in the world.

The system is totally broken and everybody knows it"— Sherman Mullin, retired former Lockheed F-22 program chief

The early cancellation led directly to a new advanced warplane, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter that Lockheed also produces. Today, that nearly $400-billion system is headed in the same direction as the F-22, falling behind schedule, encountering serious software problems and suffering sharp cost growth.

At the heart of the ongoing weapons acquisition problem, retired military leaders and defense experts say, is a failure by the Pentagon and Congress to acknowledge at the outset the true cost and technical difficulties of building complex systems like the F-22.

The military launches ambitious programs based on low-ball estimates by contractors, critics say. Eager to speed money to their home states, members of Congress allocate funding for these leading-edge defense programs, even before the technologies are developed and tested.

When predictable engineering problems cause costs to explode, Congress typically reacts by cutting the flow of money. Production is then curtailed and the Pentagon searches for a lower-cost weapon. The vicious cycle begins again.

"If everybody involved would be more realistic and didn't lie about risk, technical difficulty and cost, we wouldn't have these problems," said Thomas P. Christie, a retired official who spent nearly 50 years working in Pentagon acquisitions. "We jump into these decisions, then get surprised about the outcome."

The F-22 experienced almost every one of these problems. The Air Force began laying plans to build the F-22 in the early 1980s. A decade later, it estimated it would take nine years and $12.6 billion to develop the jet, but it ended up taking 19 years and costing $26.3 billion, not including the production of any aircraft. By the time production was completed, the F-22 cost an average of $412 million each, up from the original estimate of $149 million.

Airmen perform a hot pit refuel with an F-22 Raptor Nov. 15, 2012, at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska. (Tech. Sgt. Dana Rosso / U.S. Air Force) More photos

"The system is totally broken and everybody knows it," said Sherman Mullin, the retired former Lockheed chief of the F-22 program and a fierce advocate for the jet. "Partially, the F-22 fell victim to that."

A Lockheed spokesman defended the program, saying that the jet is "the world's dominant air superiority fighter" and that the program provided the Pentagon with an adequate fleet.

Apart from the cost, the F-22's complexity led to serious safety problems. It's had seven major crashes, two of them fatal. Defects in the F-22's novel oxygen supply system led to a three-month-long grounding last year. A Lockheed spokesman said the problem has since been solved with several technical fixes, and flight restrictions were lifted in April. But the Defense Department's inspector general recently criticized the Air Force's investigation of a fatal accident related to the oxygen system.

The saga of the F-22 began during the Cold War in Los Angeles when the Air Force held a final competition between the world's two stealth-technology leaders, Lockheed and Northrop Grumman Corp. The two companies designed prototypes — the Lockheed YF-22 in Burbank and Northrop YF-23 in Hawthorne — and built them in Palmdale.

A lot was riding on the competition that went far beyond the technical merits of the aircraft. Northrop was already building the then-secret B-2 Stealth bomber. If it had also won the fighter competition, it would have held a virtual monopoly on Air Force combat jets. At the same time, Northrop's reputation was impaired by a wide range of fraud investigations, putting Lockheed in a stronger position to build political support in Congress.

We got the feeling that they didn't care what the pilots thought,"— Ron Johnston, Air Force YF-22 test pilot

Northrop executives concluded that they were being politically crushed by Lockheed — which ended up having more than 1,000 subcontractors on the F-22 program with jobs in 44 states, giving it political muscle Northrop lacked.

"I'd go to the Pentagon by myself for a meeting and there would be 10 Lockheed people there," recalled Steve Smith, a retired Northrop executive who ran the aircraft division. "You'd try to get an appointment and there would be three Lockheed guys in front of you. We were overwhelmed."

Mullin, the former Lockheed executive, asserts that the competition itself was untainted by politics.

The technocrats who were managing the project tried to sidestep those issues, asserting that both planes met the service's requirements and giving senior officials wide berth to make any choice they wanted.

"If they decided to go out in the backyard of the White House and pitch horse shoes to see who the winner was, it wouldn't make a difference in terms of the war fighters' capability," said Eric Abell, the Air Force's top engineer on the project.

It was widely assumed that Northrop's entry was faster and stealthier, while Lockheed's was more maneuverable. But the actual capabilities of the planes were held close to avoid comparisons by anybody outside the top ranks. The service never allowed any pilot to fly both jets.

"They didn't want anybody to ask some lowly Air Force pilot which was the better plane," said Con Thueson, a former Air Force test pilot on the project. "The generals and the politicians want to make the selections. The last thing they want is some captain or major contradicting their decision."

Comparing the YF-22 and YF-23 »

The Air Force held a competition between two prototypes from the world's two stealth-technology leaders, Lockheed Martin Corp. and Northrop Grumman Corp. See the breakdown »

Ron Johnston, another Air Force test pilot on the program, said the YF-22 had a reputation at Edwards Air Force Base for poor reliability, but top Air Force officials kept favoring it, giving Lockheed extra time when it fell behind schedule. "We got the feeling that they didn't care what the pilots thought," he said.

The Air Force evaluated the two planes in 1991 with six tons of secret documents and a staff of 250 experts. The final decision was in the hands of then Air Force Secretary Donald Rice, a former president of Rand Corp, a nonprofit think tank in Santa Monica.

On the day after Lockheed won, Rice declined to say that it was the better product and cited Lockheed's superior management plan for the program.

In a recent interview, Rice conceded that the F-22 was not necessarily the better plane, saying, "There were some reasons to think that the YF-23 might be a better plane for the Air Force."

It wasn't a concern about a Northrop monopoly or its lack of political power that swayed his decision, he said, despite assertions by a half-dozen retired Northrop executives that the competition was rigged or flawed.

Rather, Rice recalled, the company scored poorly on an obscure requirement to describe how its plane could be adapted for the Navy, a criterion that was soon irrelevant when the Navy backed out of the F-22 program entirely.

Whether Northrop's plane would have turned out any better than the F-22 is impossible to know, but the unusual competition failed to address a lot of issues that later became central to the F-22's problems. Only cursory testing was done on both planes' hardware and software. The oxygen supply system was not tested at all.

After Lockheed won, it quickly ran into engineering problems, and costs escalated. In 1992, a YF-22 crashed because of a flaw in its flight-control software. Assembly of the first F-22 did not start until 2001, but even by the time the plane was operational in 2005, the software kept malfunctioning.

Congress responded by cutting the budget, which extended the schedule and drove up costs. By 1997, the buy was cut from 648 to 338, and as the costs crept up the program was killed at 188. Rice said the buy of 188 F-22s "is not enough."

Despite the F-22's cost problems, the jet is considered the most advanced fighter plane ever built. It's packed with cutting-edge radar and sensors, enabling a pilot to identify, track and shoot an enemy aircraft before that craft can detect the F-22. However, it has never been deployed in combat.

Meanwhile, one of the Northrop prototypes is parked on a distant taxiway at Zamperini Field in Torrance, slowly falling apart under the blistering sun, masking tape covering chunks missing from its wing.

And after curtailing the F-22 program, the Air Force shifted focus to the F-35 to modernize its fleet, holding a similar competition. Now, costs are exploding and the development has run into delays and technical problems.

The early termination of the F-22 has left the nation with a weaker deterrence to potential enemies, said John Pike, executive director of GlobalSecurity.org. China is building two stealth fighters, one of them able to operate off aircraft carriers, and seems able to build more than 188 aircraft, he said. "You'd have to be worried."

Follow Ralph Vartabedian (@RVartabedian) and W.J. Hennigan (@wjhenn) on Twitter

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.