Apple ordered to pay $533 million in iTunes patent lawsuit

- Share via

The bitter patent wars have flared again, and this time, Apple Inc. emerged the loser.

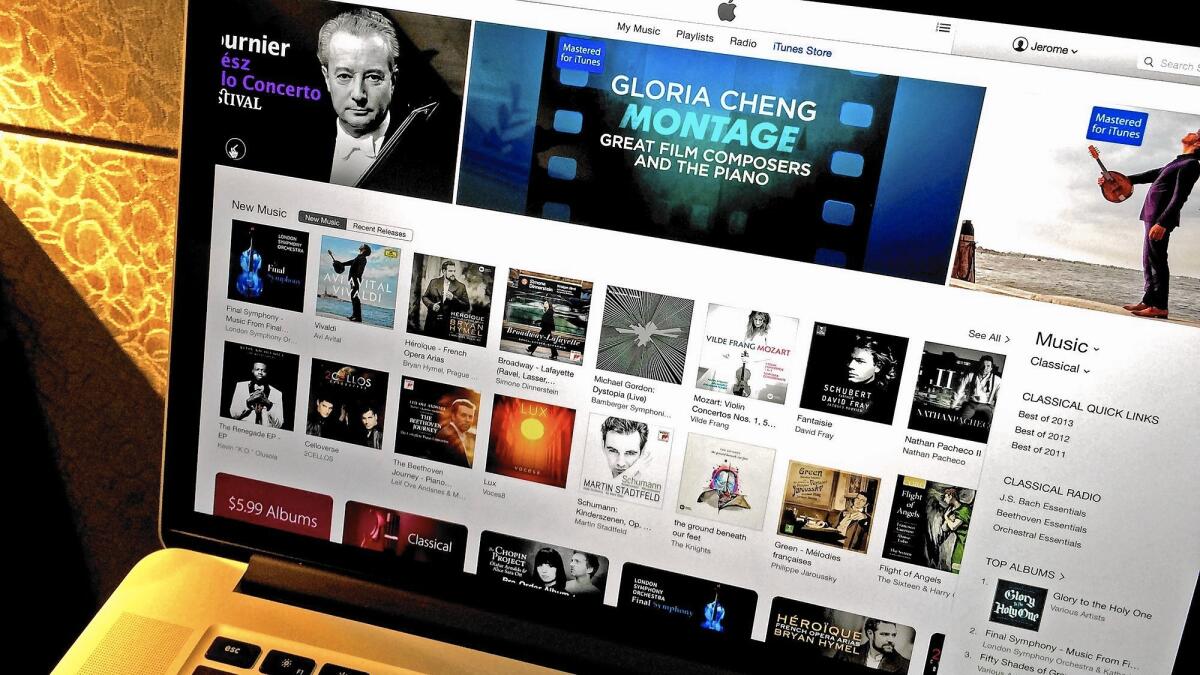

The world’s most valuable company was ordered by a federal jury to pay $532.9 million to Smartflash, a tiny Texas company that alleged that Apple willfully infringed on its intellectual property by using its patented technology in Apple’s iTunes software.

An Apple spokeswoman said the company would appeal and slammed Smartflash for what it sees as patent abuse.

“Smartflash makes no products, has no employees, creates no jobs, has no U.S. presence, and is exploiting our patent system to seek royalties for technology Apple invented,” Apple said in a statement. “We refused to pay off this company for the ideas our employees spent years innovating and unfortunately we have been left with no choice but to take this fight up through the court system.”

The case is just the latest to raise questions about what many have called a broken U.S. patent system. Last year 5,020 patent cases were filed in U.S. district courts, nearly double the 2,580 that were filed in 2009.

Companies large and small gripe about spending millions of dollars to defend against lawsuits and file suits of their own in cases that take years to resolve. Companies regard many patent suits as extortion bids, where plaintiffs hope for a big payoff or to settle out of court. Inventors, meantime, claim corporations use money and power to rip off their intellectual property.

“The more [companies] get sued, the more they pay out, the more their profits get hurt, the more they charge their customers,” said Raymond Persino, a patent lawyer at Jefferson IP Law in Washington, D.C. who also worked as a patent examiner for seven years. “So the costs get passed on to everybody.”

Legal experts say the laws exist to help companies and inventors protect valuable intellectual property, for use in their own products and services or to license to others.

But in recent years new players in patent courts have gained force — so-called patent trolls, companies or individuals who use the patents they own mainly to sue possible infringers for financial gain; often, those patents aren’t part of any products or licensed for use to anyone.

Who qualifies as a troll is a subjective judgment.

“Patent troll is a term that is thrown out too much,” said Jim Bergman, an intellectual property expert at financial advisory and consulting firm Conway MacKenzie. “There are plenty of cases in which that may be an appropriate term, but there are legitimate nonpracticing entities that hold valuable patent assets that have the right to enforce them.”

John Austin Curry, a lawyer representing Smartflash and its co-founder Patrick Racz, said his client is no troll.

Instead, Racz had attempted to launch a line of products in the late 1990s based on his ideas, but the business venture fell through, Curry said. So Racz did the “prudent thing” and filed for patent protection in 2008.

Smartflash, he said, exists primarily to protect the patents. The company also has patent suits open against Google Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co.

With deep pockets and a global name, Apple is a top target for patent trolls. In court filings last year, the company said it had faced nearly 100 such lawsuits in the last three years.

The number of patent cases nationwide has swelled in recent years — they’ve risen every year since 2009 with the exception of a drop in 2014. Apple revealed the data as part of a broader push by the tech industry to enact new rules that would deter patent trolls.

On Wednesday, Apple reiterated the urgency, saying the Smartflash case was “one more example of why we feel so strongly Congress should enact meaningful patent reform.”

Smartflash holds patents that cover methods for selling digital music, games and other content. After wading through complicated technical arguments, the jury in Tyler, Texas, decided late Tuesday that Apple infringed on three Smartflash patents.

Smartflash alleged that Racz discussed the data management technology in 2000 with Augustin Farrugia, who later became a senior director at Apple, according to Smartflash’s complaint.

“Apple is very bitter about the outcome,” Curry said. “They are talking about the broken system, but they wouldn’t be saying that if they had won.”

Although Apple was on the losing end of the Smartflash case, it has been the aggressor plenty of times. It has brought patent infringement cases against Samsung Electronics, Motorola, HTC and other tech competitors that it deemed were stealing its technology.

The US. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas has emerged as a popular venue for patent disputes with a reputation for speedy trails and juries apt to side with plaintiffs. Apple has had some luck fighting such cases in court: At least two other high-profile patent decisions against Apple from East Texas have been reversed on appeal.

“In reality, this Smartflash case — they’re just at halftime,” Bergman said.

The larger concern is whether enough inroads can be made to meaningfully improve the patent system. While there have been some patent reform developments, “much more remains to be done,” said Michael Zeller, a partner at Quinn Emanuel not involved with the case.

“We need to ensure that the patent system works to promote innovation,” he said, “rather than hurt it.”

Twitter: @byandreachang, @jpanzar

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.