Grove builder Rick Caruso reimagines Miramar resort with splashes of seaside splendor

- Share via

In a quiet garden at the Rosewood Miramar Beach resort in Montecito is a white marble statue of the Buddha, laughing while four small children clamber up his side.

The latter is a clue this is not your typical religious shrine.

The Buddha had only one child, according to texts, but resort owner Rick Caruso has four — and so the playful stone statue has a bigger brood.

It’s just one of the subtle references to the Caruso family that can be found at the new resort, which may be the most intensely personal — and upscale — project yet for the Los Angeles real estate magnate.

Caruso, who started his development career with a modest mall on La Cienega Boulevard, went on to build successively grander shopping venues including the landmark Grove, the Fairfax District “lifestyle center” that pioneered a wave of outdoor malls that meld shopping with food and entertainment.

Last year, he completed a $200-million village center for tony Pacific Palisades with small shops and restaurants evocative of East Hampton’s main street.

Now, the 60-year-old has reached higher still, completing his first venture into the hotel business with a splash that he hopes will earn the Miramar prestigious five-star and five-diamond ratings.

And it has prices to match, with rooms that cost more than $800 a night on the low end and reach $5,575 for a grand suite. Rooms over the sand begin at $1,075 a night.

Its nearest competitors are the four-star Four Seasons Resort the Biltmore Santa Barbara and the four-diamond Ritz-Carlton Bacara, Santa Barbara.

And though it is operated by Rosewood Hotel Group, a Hong Kong-based chain with luxury hotels across the globe, it is very much a Caruso property.

Among other family references are his children’s initials capping the directional arrows on a weather vane and the Caruso family crest mounted discreetly amid a leaded glass window overlooking the Pacific.

Then, point blank, there is Caruso’s, the resort’s swank Italian restaurant.

Patrons can dine a few feet above the sand, viewing the surf from high-backed booths intentionally reminiscent of Perino’s, a midcentury Los Angeles restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard that catered to the city’s business and entertainment industry elite for decades.

Caruso hopes the Miramar won’t change hands again for a long time, which is one of the reasons he added so many personal references during its creation.

“I build them with the hope and dream they will stay in the family until the end of time,” he said. “It’s just a fun thing to create a link between generations.”

On a recent chilly afternoon, Caruso cut a rakish figure strolling through the hotel’s Manor House in a snug gray double-breasted suit, wearing dark glasses and trailing behind his leashed dog Dodge — very much carrying himself like the man Forbes said is worth $4 billion. The docile golden retriever is his constant companion and later fell asleep at Caruso’s feet as he sat in the Miramar’s main restaurant, Malibu Farm, which serves farm-to-table fare.

Caruso appeared a bit weary himself, understandably. After buying the property for $50 million in 2007, he spent more than a decade working with the neighbors and navigating a complicated approval process that required applications to state, county and local agencies. In recent months, it was a race to get the resort ready for its March 1 official opening date, with nearly 1,300 laborers a day working double shifts.

And he’s had other duties in addition to running his existing properties and building in Pacific Palisades. As chairman of the USC Board of Trustees, he has faced tumult in recent months including the removal of Marshall School of Business Dean James Ellis and a $215-million settlement for former patients of disgraced campus doctor George Tyndall in a sexual abuse scandal.

Amid the tumult, he’s kept focused on his ambitious goals for the Miramar, which he proclaims are nothing less than “to reinvent hotels” — with a nod to the customs of yesterday’s leisure class. “The grand old hotels of Europe were more like residences.”

Caruso has a reputation as a big-spending developer who packs expensive details into his projects to help give them the kind of visual punch that led the Wall Street Journal to call him “the Walt Disney of retail” last year.

The Grove and the Americana at Brand mall in Glendale reflect his bent for extravagance and his personal tastes, such as jaunty Frank Sinatra tunes piped outdoors and, at the Americana, an 18-foot-tall gold-plated statue called “Spirit of American Youth” rising in the middle of a dancing fountain.

At the Miramar, however, Caruso has gotten a chance to indulge the tastes developed first through his childhood in Beverly Hills and later through accumulation of the fortune that has made him one of the wealthiest businessmen in Los Angeles.

The resort takes some broad design cues from the Beverly Hills Hotel, which took its famous form during a 1940s makeover created by Paul Williams, a revered Los Angeles architect whose influence now pervades the Miramar.

Perino’s signature booths were designed by Williams, who died in 1980. The hotel is meant to have the look and feel of a grand 1930s home designed by Williams, starting at the black lacquered front door with a brass mail slot.

Inside, guests find themselves in a soaring mansion-style foyer flanked by a curving staircase made using Williams’ blueprints for a legendary home completed in Beverly Hills in 1933 for auto titan E.L. Cord.

When you allow people to have fun, you make money. They become loyal, and they come back.

— Miramar developer Rick Caruso

Caruso explains that Williams’ granddaughter is a friend and shared Williams’ hand-drawn plans for the Southern Colonial-style Cord estate, which Caruso framed and mounted discreetly near the foyer.

The residential sensibility prevails throughout the hotel designed by a team led by architect Dave Williams (no relation to Paul Williams), Caruso’s executive vice president of architecture. From the front door, visitors can see straight through what looks like a casually elegant living room and veranda, past a wide lawn and finally to the ocean.

Most of the 16-acre site — almost as big as the Grove but with a feel much larger since little acreage is taken up by parking — is landscaped open space, which Caruso hopes will help put guests in vacation mode. “It’s to lower everyone’s blood pressure,” he said.

In addition to the Manor House, which includes a spa, there are bungalow-like guest room buildings spread along meandering paths. There are two swimming pools and seven eateries, including a poolside shop that serves hamburgers and local ice cream.

He declines to talk about how much the Miramar cost, but Bacara reportedly cost $222 million to build in 2000.

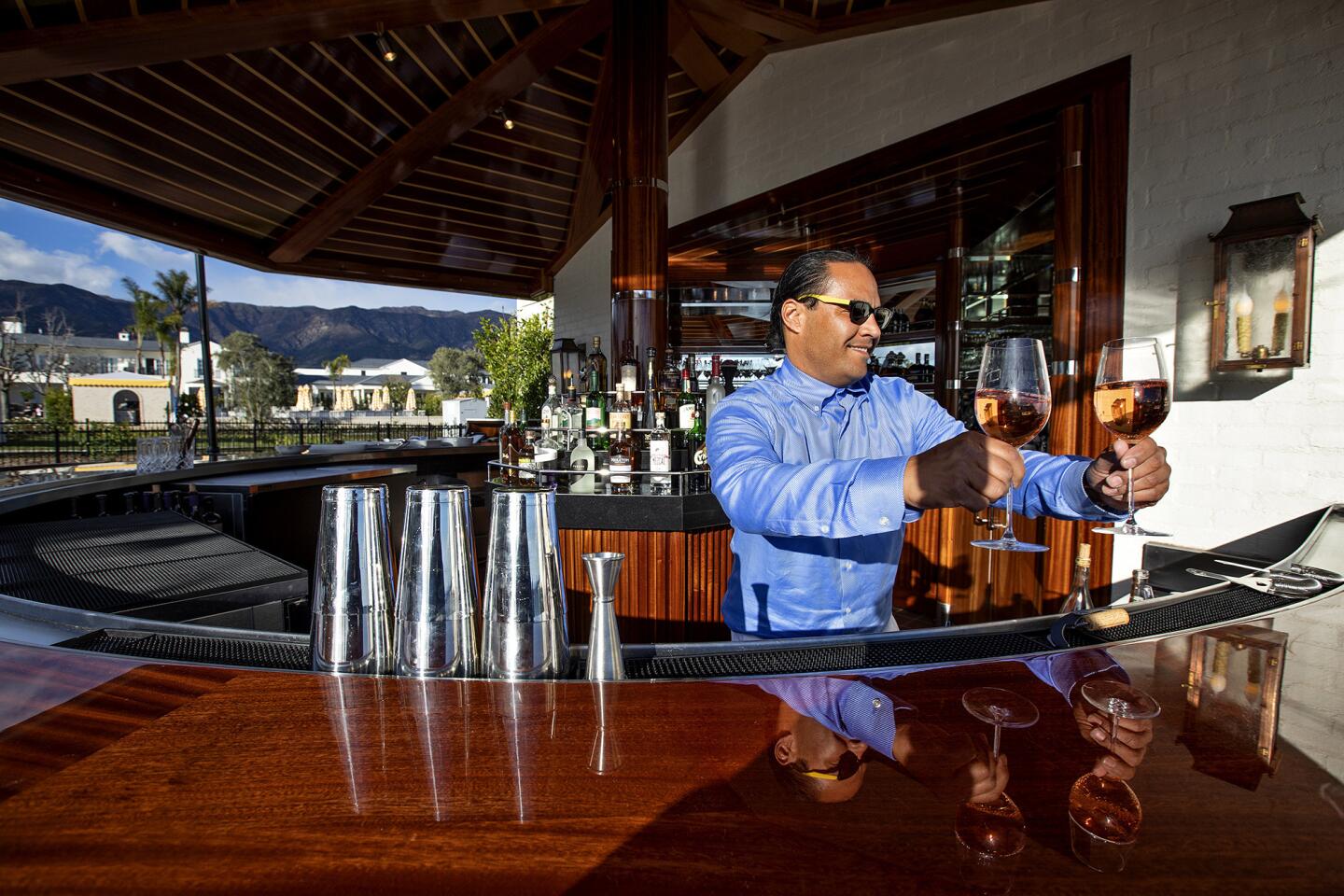

Pricey design flourishes and materials can be seen in all directions at the Miramar including a Brazilian walnut deck at the seaside bar, hand-painted wallpaper and custom-designed Baccarat crystal chandeliers in the ballroom.

Original artworks abound, including a 1937 Norman Rockwell painting called “Scout of Many Trails” in an event space called the Study and a whimsical Fernando Botero painting titled “Two Drunks” in the Manor Bar.

The sundry shop is a Goop store, founder Gwyneth Paltrow’s first outlet in a hotel.

I don’t have investors. I get the freedom to make decisions I think are best.

— Miramar developer Rick Caruso

Caruso builds in a way many other developers would consider extravagant because he can. “I don’t have investors,” he said. “I get the freedom to make decisions I think are best.”

But Caruso is ever watchful of his bottom line.

The 161-room resort already has 25 weddings booked, and he has other ideas for programming that Caruso has honed in his retail centers, along with advertising sponsorships and promotions such as “date night” and “Mommy and me” events.

He pictures people wandering up to the hotel bar after a barbecue “burger bash on the beach” and smiles as he contemplates the promise held by the resort’s two bocce courts — a bowling game that has become hip but is ancient and hints at Caruso’s Italian heritage.

“I bet the bocce ball league will bring in $1 million a year alone,” he said.

And Christmas, sometimes a slow period for seaside resorts, will be celebrated fancifully with decorations including trees for each room that guests can decorate themselves with provided ornaments or let the hotel staff do the job.

“When you allow people to have fun, you make money,” he said. “They become loyal, and they come back.”

Donald Wise, a hotel investment banker at Turnbull Capital Group, estimates that it will take five years to get the Miramar financially stabilized, but Caruso is in position to make it to that point.

Caruso “is obviously very well capitalized, unlike a lot of developers who have to put things together with mirrors.”

Indeed, the Americana at Brand opened in 2008 amid the financial crisis, but Caruso weathered that storm.

The Miramar is one of only a handful of hotels in Southern California that is directly on the beach, which gives it a competitive advantage, said Wise, who was not involved in its sale or development.

Rosewood, which operates luxury properties across the U.S. and some two dozen countries, could help deliver the top-level five-star and five-diamond industry ratings Caruso seeks, Wise said. If that happens, the Miramar would probably be the only five-star hotel in the world with an active railroad running through it.

Ten freight trains and two passenger trains roll through each day on tracks that cleave the edge of the property between the main Manor House complex and the waterfront suites, bar and Caruso’s restaurant.

To diminish its impact, Caruso raised the level of the hotel grounds. “The train loomed over you before,” he said. “We put a cool bar by it, and now it’s part of the experience” of being at the Miramar. The nearby beach guest rooms also are on base isolators to contain vibrations from the trains.

For many years guests arrived at Miramar by train, starting in the 19th century when the Miramar became a favored destination of the well-to-do including snowbirds from the East who would spend winter there.

The inn’s history dates to the 1880s, when landowners Josiah and Emmeline Doulton turned part of their farm into a hotel, said Michael Redmon, director of research at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum.

The Doultons soon named it Miramar, or “Behold, the sea” in Spanish. By 1902, The Times was reporting on arrivals of the well-to-do, such as the widow of a railroad magnate who arrived from Boston for the season with her maid and chauffeur in tow.

The Miramar is remembered perhaps best among the living as an unassuming seaside getaway where families with kids and dogs could afford to spend a relaxing weekend nestled between the peaceful Pacific and dull roar of Highway 101.

The Doulton family sold the Miramar in 1939 to Paul Gawzner, who revamped the property and added a swimming pool. By the late 20th century, the resort was known to some for its air of “Catskill kitsch” — with its shuffleboard courts and waiters who once tooled around the grounds on bicycles, trays from the kitchen mounted on their baskets.

Gawzner sold the Miramar in 1998 to night club and hotel impresario Ian Schrager, who closed the inn in 2000 to make renovations. Work stopped as the economy soured and the partly demolished hotel became a local eyesore.

Toy manufacturer Ty Warner, who became a billionaire through his Beanie Baby plush toy line, bought the Miramar in 2005 with plans to renovate the property but ended up selling it to Caruso less than two years later.

Caruso razed almost the entire site, saving only the original owner’s wooden residence, which stands just off the hotel grounds. It’s being restored, but no use for it has been planned yet.

For now, Caruso is just enjoying his accomplishment of getting the Miramar up and running — a satisfaction he is sharing with his family.

The Carusos, including Rick’s wife of 31 years, Tina, have their own residence in the Manor House.

Gigi Caruso, Rick’s youngest child at 18, said she and her siblings are taking particular pleasure in the family references her father slipped into the development, including quotes from their favorite literary figures painstakingly inlaid into stones on the veranda.

“It’s so fun seeing all our personal family references around the property,” she said. “It means so much to us that he involved us in the process.”

The developer’s next planned venture is residential. He built an ultra-deluxe 87-unit apartment building on the eastern edge of Beverly Hills in 2012 and now plans to erect a bigger one nearby on the site of his first development on La Cienega Boulevard that housed a Loehmann’s department store.

But that wasn’t really on his mind as he watched some of his first patrons enjoy the food at Malibu Farm. Instead, he’s just settling in at the Miramar.

“It was years of work,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.