Record trade deficit will put pressure on Trump in upcoming China talks

- Share via

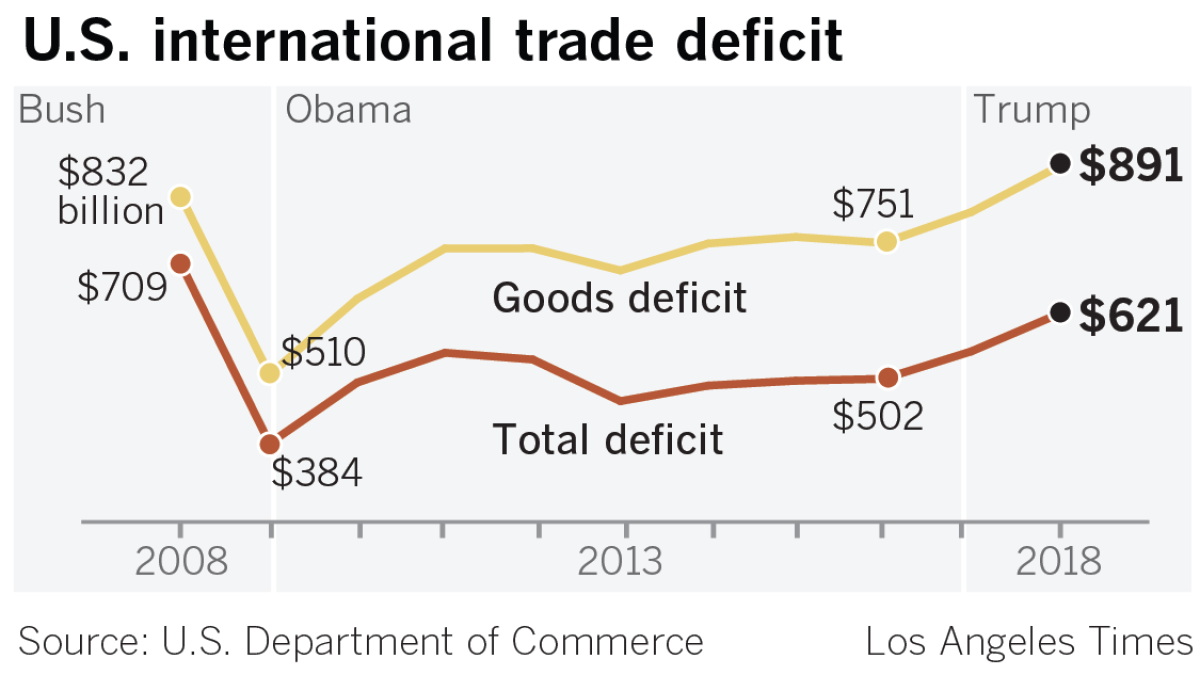

Reporting from Washington — President Trump fell further behind in his goal of reversing the nation’s trade deficit as the gap in goods soared to an all-time high last year.

That’s certain to add pressure on Trump to close a trade deal with China to boost U.S. exports and remove punishing tariffs against American farmers and other businesses.

The U.S. trade deficit with the rest of the world surged 12.5% last year to $621 billion, with the goods portion of the shortfall reaching a record high, the Commerce Department reported Wednesday.

In Trump’s first two years in office, the overall deficit in traded goods and services has surged by nearly one-fourth — and it’s in large part due to the president’s own policies.

Trump’s big deficit-financed tax cuts last year helped fuel economic growth as well as the strength of the dollar, and those trends spurred U.S. purchases of foreign-made goods, especially from China, Mexico and Europe.

“We’ve stimulated our economy in such a way that sucks in a lot of imports,” said David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank.

At the same time, Trump’s trade war with China led to tit-for-tat tariffs last year. And although the United States imposed duties on about $250 billion of Chinese goods — more than double what China slapped on U.S. products — the statistics suggest that the U.S. was hit harder than China.

Total U.S. goods exports to China fell 7% last year to $120.3 billion, but American imports of Chinese merchandise rose by that same percentage, to $539.5 billion.

Separate data from China’s customs administration provide part of the explanation. Chinese purchases of U.S. soybeans — one of America’s top exports, which were targeted by China’s retaliatory tariffs — fell by half last year to $7.1 billion from $13.9 billion in 2017. The U.S. loss was Brazil’s gain, as that country’s soybean exports jumped by $8 billion.

There were also notable declines in U.S. shipments to China of frozen fish and American-made cars, among the other products hit by higher tariffs.

“The president talks a lot about trade, tweets about trade, blusters about trade,” said Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing. “The truth is, he’s made only selective interventions but nothing that would tip the scales on the trade deficit.”

“At the end of the day, the data don’t lie,” he added. “Right now, things are getting worse, not better.”

Trump has been less fixated on the trade deficit in recent months as it has become apparent that the number was going up. Economists widely agree that Trump’s emphasis on the trade balance is misplaced, because that number reflects broader economic factors, mainly the gap between a nation’s investment and savings. Tightening fiscal policy and increasing incentives for savings are two ways to help lower the deficit, neither of which has been pursued by the Trump administration.

Even so, the administration is betting that the president’s rampant use of tariffs to push trading partners to the negotiating table will lead to higher U.S. exports and more opportunities for American businesses and workers.

Trump’s chief trade negotiator, Robert Lighthizer, last year concluded a revision of the North American Free Trade Agreement, and he is currently trying to wrap up a deal with China.

If talks advance, Trump has said he and Chinese President Xi Jinping could meet later this month, most likely at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, to finalize an agreement.

It remains to be seen whether Trump will agree to a removal of tariffs on Chinese goods, something that Beijing is seeking in exchange for large purchases of U.S. products, including soybeans and liquefied natural gas. The U.S. is also pushing China to open its markets in services and other sectors.

With the trade deficit rising and U.S. businesses increasingly complaining about the pain from tariffs, Trump is under pressure to strike a long-term truce with China. And he may settle for a deal that falls short of Beijing agreeing to make concrete and enforceable changes to curb theft of U.S. intellectual property, including cyber-theft. Others worry Trump will go soft in demanding that China drop various means of forcing foreign firms to hand over technologies and trade secrets to do business in China.

In recent days, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, among others in the administration, have been visiting farmers and constituents to shore up support in rural areas and political battlegrounds in the Midwest that are particularly sensitive to trade.

Farmers and other businesses, although many of them still largely back the administration, say they are anxiously awaiting the outcome. The trade war with China has been a dark cloud that has damped investment. And despite Trump’s insistence that the Treasury has taken in billions of dollars in tariffs from China, experts say the weight of the tariffs has been borne by U.S. businesses and consumers, including many GOP voters.

“My hope is that toward the end of March, there would be an announcement, anything that would open up our grains going back into China,” said Kent Winter, a fifth-generation farmer near Wichita, Kan., whose exports of sorghum and soybeans last year were hammered by Beijing’s retaliatory tariffs.

Douglas Irwin, an economics professor and trade historian at Dartmouth College, said a deal with China that includes promises of big purchases of American goods could help lower the trade deficit in the short run. But even if the purchases amount to hundreds of billions of dollars over some years, that still wouldn’t guarantee a major impact on the U.S. trade balance.

It’s not clear, for example, that the U.S. has the capacity to produce that much more energy or farm goods to meet new demand. So some of the increased U.S. exports to China will mean a diversion of sales that had been going to other countries.

“It’s more substituting, a reshuffling of trade,” Irwin said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.