Ratepayers get the shaft in San Onofre fiasco

There are train wrecks, and there are train wrecks. Then there’s San Onofre.

You probably know San Onofre as the full-figured fiasco overlooking the Pacific Ocean near the Orange/San Diego county line. Beginning in 2004, Southern California Edison, the nuclear power plant’s principal owner, oversaw a $770-million project to replace its two aging steam generators with new models. The new units, which were supposed to last 20 years, lasted scarcely 20 months before showing alarmingly severe wear and tear.

The plant was shut down. Neither of its two units, which are designated units 2 and 3, has generated a practical watt since the end of January 2012. They may never operate again. (The troubled Unit 1 was permanently shuttered in 1992.)

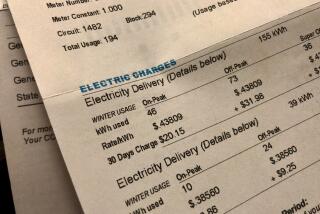

But while San Onofre’s electrons are but a memory, the billing lingers on — nearly $1 billion charged to ratepayers of Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric Co., the plant’s minority owner, over the last year, according to the Public Utility Commission’s Division of Ratepayer Advocates. The money is still flowing out of the pockets of the two utilities’ 6.4 million billed customers at the rate of more than $68 million a month. Some of that may be refunded to customers, but possibly not for years.

With so much money at stake, it’s unsurprising that in recent months the question of who pays for San Onofre, how much, and when has dominated the discussions about the plant before the PUC. It’s a fair bet that, in time, the volume of legal briefs on those issues will far exceed those relating to the more basic questions of what happened and whose fault it is.

That’s because the latter questions have mostly been answered: The replacement steam generators were poorly designed, and the responsible party is Southern California Edison. Even if it turns out that the generators’ builder, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, screwed up the job, that happened on Edison’s watch. As far as ratepayers are concerned, the utility is “it.”

That points to the basic philosophical issue of why Edison’s customers, and not its shareholders, should continue to pay for a nuclear plant that shows as much life right now as a raccoon flattened by a semi-truck on the 5 Freeway. Edison is hoping to restart Unit 2 sometime this year, depending on approval from the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission, but even then it would be run at 70% of its rated power and only for a five-month test. As for Unit 3, no plans have yet been released for getting it operational.

The longer the utilities keep collecting money for this road kill, the more the inequities pile up: Even if the utilities are eventually ordered to refund some or all of the costs of San Onofre, who will get the money? It’s unlikely that Edison would be ordered to track down every ratepayer who has moved away. So the “refund” might take the form of lower rates in the future — but how confident can you be that the complex accounting required would be perfectly accurate, dollar for dollar?

Accordingly, the only fair way to deal with the cost of San Onofre is to stop letting the utilities collect it, by taking the plant out of their rate base instantly.

It’s useful to keep the following timeline in mind. State law required the utilities to formally notify the PUC of the San Onofre shutdown once it had been on the fritz for nine months (that is, around Oct. 31.) At that point, the PUC had up to six weeks to institute a formal order of investigation, and at that point it could designate the money still being charged ratepayers for the plant as refundable — depending on how much of the fiasco it ultimately decided was the utilities’ responsibility. The PUC issued the order of investigation on Nov. 1.

The debate over billing centers on two issues. One is whether the PUC can take San Onofre out of the utilities’ rate base any time it chooses. The other is whether the PUC can order refunds of already-charged San Onofre costs going back to Jan. 31, 2012, when the plant effectively went down.

Edison says the answers are no, and no. The firm contends that state law allows refunds to be dated only from the point of the formal order of investigation, and that the order can’t be dated earlier than nine months after the outage. It adds that the PUC can’t change its rates, even if San Onofre is judged to be a total loss, until it considers its next general rate case. That’s a huge proceeding designed to set the utility’s overall rates for three years. Edison’s last rate case ended last year. Its next one won’t start until 2015.

In other words, Edison says the PUC can’t keep it from charging ratepayers for San Onofre for many years to come, and that the money billed and received for at least 10 months the plant was dark during 2012 can’t be refunded.

Edison’s position is that it’s just following the law. “We have statutes and a regulatory process we abide by,” says its spokeswoman Jennifer Manfre. Retroactively changing the rules just for San Onofre, she says, would saddle the utility industry with an unfair “regulatory uncertainty.”

Ratepayer advocates say that’s all hooey designed to allow the utilities to hold on to money they’ve squeezed from ratepayers for services not rendered, and to defer a final accounting. They say the PUC has the legal right to take a useless power plant out of the rate base whenever it wants, and that halting collections for San Onofre is long overdue.

They’re especially galled over Edison’s contention that any refunds must be delayed until it knows how much the utilities recover for the shutdown from Mitsubishi and their insurance companies, or in lawsuits.

“We’re not sure why ratepayers should be responsible for Edison’s success or failure to collect from insurers,” says Matthew Freedman of The Utility Reform Network, or TURN. If matters end up in court, he adds, “we don’t want ratepayers to be on the hook for the Edison lawyers’ ability to make good or bad arguments.” The right solution, he says, is for the PUC to hold Edison responsible to the ratepayers, period.

Be prepared for Edison to play the poverty card in its efforts to hang on to ratepayers’ money as long as it can. In a brief it filed with the PUC last month, it said that cutting off its San Onofre-related customer billings would “hamper” its efforts to ensure that the plant is “available and operational.” Keeping San Onofre operational, obviously, is a train that left the station long ago, and long ago ran off the rails.

If Edison had to stop collecting $54 million a month (its share of the total ratepayer billings), would it be unable to keep working to fix San Onofre? Hardly. That would add up to about 5.5% of the nearly $12 billion in revenue its parent, Edison International, collected last year. The change would mean a gain for the average ratepayer, though it might require a reduction in the $1.35 annual dividend per share paid out to stockholders.

But isn’t it about time that they feel a little bit of the pain their customers have been suffering?

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears Sundays and Wednesdays. Reach him at mhiltzik@latimes.com, read past columns at latimes.com/hiltzik, check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @latimeshiltzik on Twitter.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.