How the rich get an undeserved windfall from Social Security

- Share via

In a world where the rich always seem to get richer whatever the game, Social Security always seemed to be one program that was truly “progressive” — it benefited the working class more than the moneyed class. Right?

Sadly, no.

In reality, despite painstaking efforts to ensure that Social Security benefits are distributed fairly, the wealthy are receiving disproportionately large payouts after all. That’s the finding of a new study by Alicia H. Munnell and Anqi Chen of the authoritative Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Much has changed. ... Interest rates have declined; life expectancy has increased; and longevity improvements have been much greater for higher earners.

— Munnell and Chen, Boston College

The mismatch lurks within the adjustments made both when workers claim Social Security benefits early — that is, before their full retirement age — and late. Claim early, and monthly benefits will be reduced; claim late, and they’ll be raised. These adjustments aim to make the timing decision actuarially neutral: On average, total lifetime benefits should remain equivalent whether one claims before one’s full retirement age or later.

Munnell and Chen calculate that the actuarial adjustments are out of whack and favor late claiming. “As a result, they increasingly favor higher earners,” they write.

Sigh.

Munnell and Chen identify two culprits in throwing off the math: One is interest rates, which have been lower than experts at the Social Security Administration and on Capitol Hill anticipated when they set the differentials. (The early-retirement option was made available for women in 1956 and for men in 1961. The credit for delaying retirement was introduced in 1972 and recalculated in 1983, according to the authors.)

A leading conservative and leading liberal agree that 401(k) plans aren’t doing enough to help Americans save for retirement.

The second factor may be more significant: Average life expectancy is rising. As a result, retirees are collecting benefits for longer than the designers expected. Longevity is rising faster for wealthier individuals than middle- and lower-income workers, however, which is what makes late claiming more of a boon for the wealthy.

In the six decades since retirement options were broadened, Munnell and Chen write, “Much has changed.... Interest rates have declined; life expectancy has increased; and longevity improvements have been much greater for higher earners.”

Munnell and Chen assert that because of these two factors the penalty for early retirement is now too high. The bump up for delayed retirement is about right on average, they say, but because of the demographics favoring the wealthy, it’s too large for those who delay.

Before exploring the ramifications of these findings, let’s look at how early and late retirement affect Social Security benefits.

A Social Security reform measure in 1983 raised the full retirement age from the traditional 65 in incremental steps. For those born in 1943-54, including those reaching 65 this year, the full retirement age is 66. For those reaching 65 next year, it will be 66 and 2 months. The change tops out at age 67 for those born in 1960 or later.

Workers can start claiming benefits as early as 62, though monthly benefits are reduced by about 6.7% for every year prior to their full retirement. At the other end of the spectrum, workers can defer benefits until age 70, for a roughly 8% bump in monthly benefits for every year deferred.

Consider workers reaching 66 this year, when the average retirement benefit is $1,474.77 per month. Early retirement at 62 would reduce the monthly stipend by about 23%, while deferring until 70 would raise it by about 32%. So if those workers had started taking benefits four years ago, at age 62, they’d be entitled to only about $1,135.57 per month. If they hold out until 70, they’ll get more than $1,947 a month. That means a reduction of about $4,000 a year for early retirement, and a gain of $5,667 a year for waiting.

For those expecting to collect the maximum benefit of $2,861 a month at full retirement age this year, early retirement at 62 would have reduced that to $2,209 a month, and deferral to 70 will raise it to $3,770.

Elizabeth Warren’s plan, like the others, addresses many of the shortcomings long identified by the program’s advocates, columnist Michael Hitzik writes.

Those figures explain the common advice to retirees is to wait as long as possible to start claiming. Of course, the advice isn’t right for everyone. It does take more than 12 years of the higher maximum payouts after reaching age 70 to make up for the four years of skipped benefits after age 66, so retirees would need to factor their health expectations into the decision to wait.

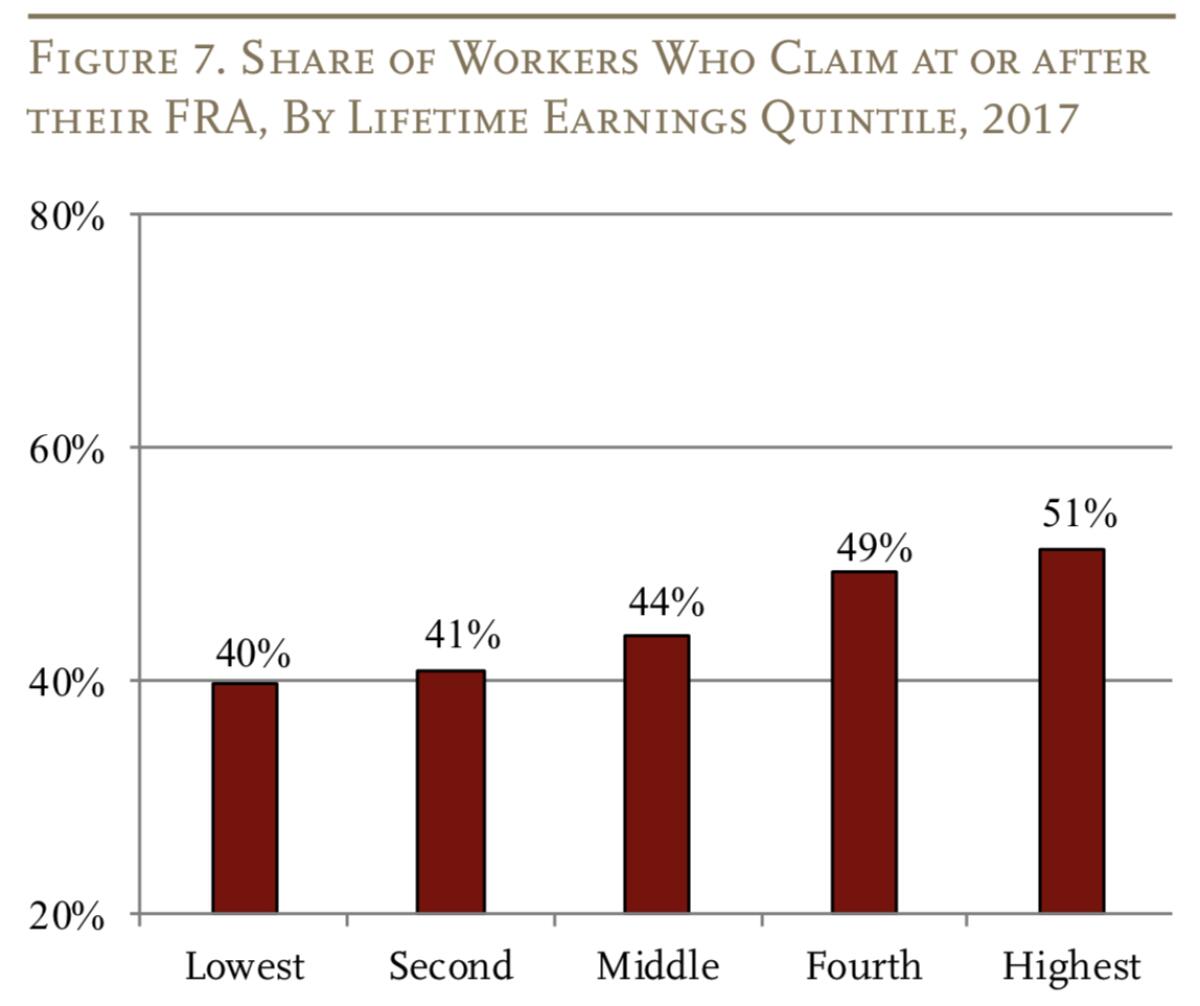

More to the point, deferring Social Security isn’t practical for many working people. Some are in jobs that are too physically taxing to continue too far into their 60s. Some don’t have savings, pensions or other sources of income to live on. Indeed, among the top 20% of earners, just over half claim their retirement benefits at or after their full retirement age. Among the bottom 20%, however, nearly two-thirds claim early.

The salient point is that deferring Social Security tends to become a more inviting option the higher one’s income and larger the nest egg. That advantage is compounded by such recipients’ longer average lifespans.

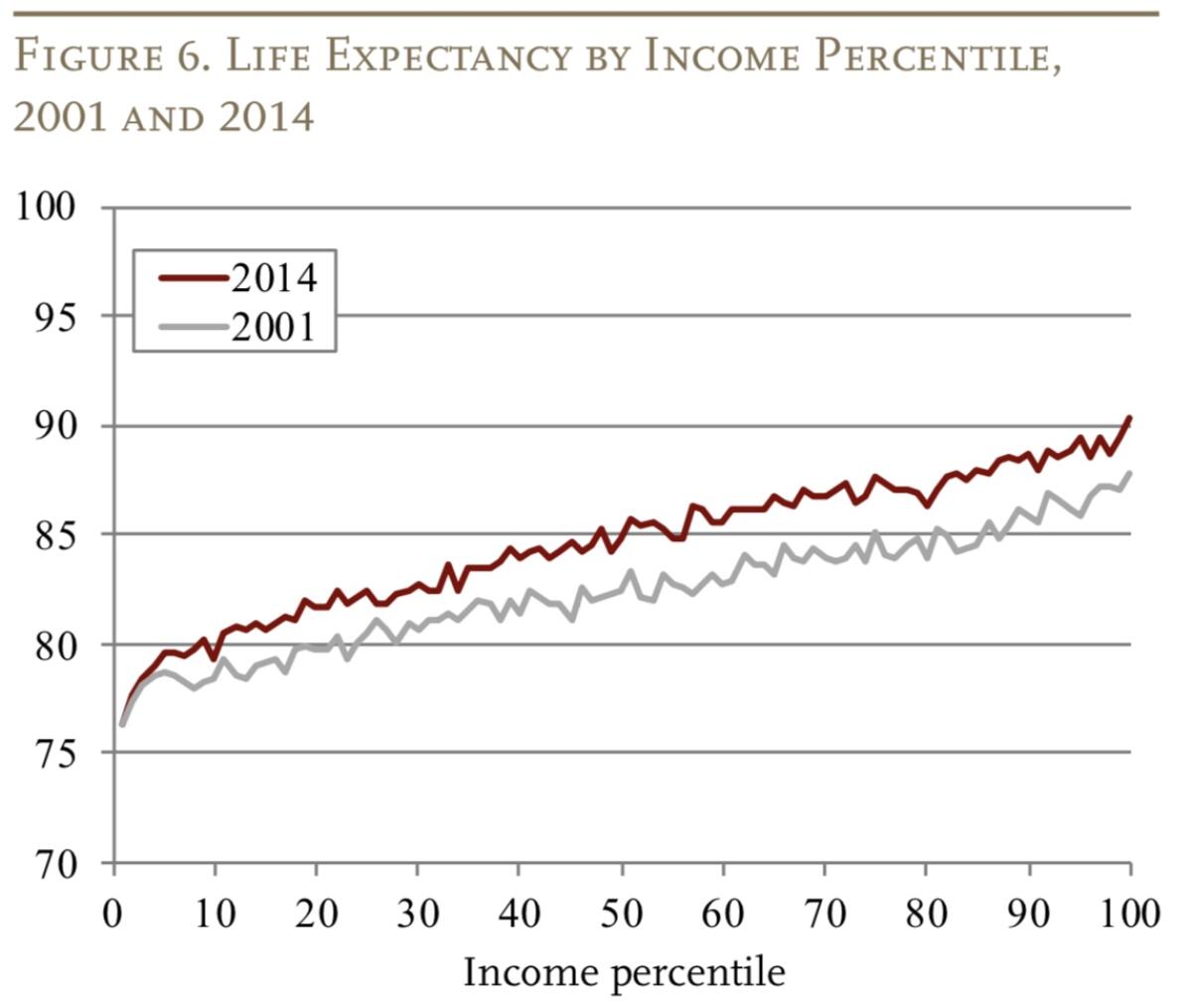

As a research team led by economist Raj Chetty of Stanford reported in 2016, among the top 1% of earners (average household income of about $2 million), the average life expectancy is about 89 for women and 87.3 for men. Among the bottom 20% (average household income of about $25,000), the average life expectancy is about 83 for women and 78 for men.

The differential is based not only on income. Average life expectancy is higher for whites than for African Americans and rise with educational attainment.

As we’ve reported before, the longevity gap between rich and poor has been widening, largely because life expectancy for those in the bottom 20% has stagnated or even moved backward, while it has soared for those at the top.

The National Academy of Sciences calculated in 2015 that for those born in 1930, males in the bottom 20% who reached age 50 had a life expectancy of 76.6; those with the same characteristics born in 1960 could expect to live only to 76.1. Among the top 20% of income earners, males born in 1930 could expect to live to 81.7, while those born in 1960 could expect to live to 88.8. In other words, a longevity gap of just over five years between rich and poor born in 1930 widened to nearly 13 years for those born in 1960. A similar pattern can be found among women.

That trend line in itself made Social Security less progressive — less advantageous for lower-income workers than for the better-off. It also undermined the argument that Social Security could be made fiscally healthier by continuing to raise the retirement age. It would, but at the expense of the working class. The National Academy of Sciences reckoned that raising the official retirement age to 70 would reduce the benefits of those in the lowest fifth of income earners by 25%, but by only 20% for those in the top fifth.

Munnell and Chen don’t make specific recommendations about what adjustments should be made in the early- and late-retirement differentials, beyond stating that they’re outdated. Curiously this aspect of Social Security benefits is seldom, if ever, addressed by reform proposals from either left or right. (Progressives generally advocate expanding and raising benefits, while conservatives want to cut them or turn the entire program over to the private sector.)

Redressing the imbalance may not be that difficult. The early-retirement penalty should be recalculated -- that is, reduced -- based on the recent history of interest rates and changes in expectations for their future course.

Reducing the late-retirement credit, currently 8% per year of deferral, is somewhat more complicated. “For the individual with average life expectancy, the reduction for early claiming is too large and the delayed retirement credit is about right,” Munnell and Chen observe. The problem with the credit is that it’s right on average but too good for those who actually tend to receive it, i.e., the wealthy.

Finding a way to make the credit fair across the entire income spectrum may require some imagination. But the options could include increasing the income tax on Social Security benefits for high-income taxpayers. Currently, up to 85% of benefits are taxable for those with income of more than $34,000 for individuals or $44,000 for couples. (In other words, a taxpayer’s tax rate is applied to 85% of benefits, not that 85% of benefits is taxed away.) Tweaking that formula, say by making 100% of the benefits claimed by richer retirees subject to tax might help bring the credit effectively back into line.

The report by Munnell and Chen underscores the inequity bequeathed to Social Security by demographics. The wealthy not only live longer than their poorer colleagues, but they also get an additional windfall from outdated math. That’s how the world works, but that doesn’t make it right.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.