Amway sued by ‘independent business owner’ claiming employee status

- Share via

Amway Corp. has long faced controversy over its multilevel marketing business model. Now, the family-owned direct sales giant is accused in a lawsuit of ripping off the people who peddle its products by failing to pay them minimum wage.

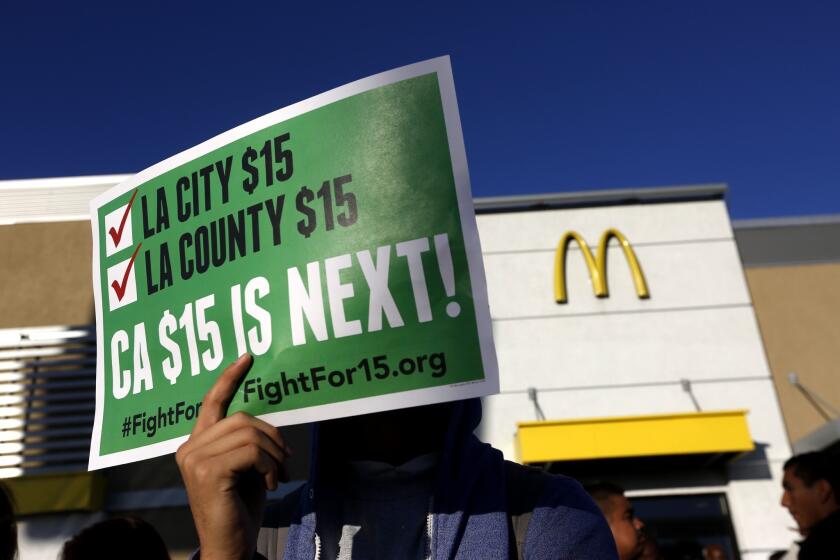

It’s part of a wave of cases in California over who counts as an employee, a battle that has heated up with a new state law that makes it harder for companies to classify workers as independent contractors to avoid giving them better pay and benefits.

Amway relies on what it calls “independent business owners,” or IBOs, who pay fees and buy its merchandise to sell to others, historically friends and neighbors. “Outside salespersons” are not typically treated as employees under California law, but William Orage claims in a suit filed Friday in state court in Oakland that his “principal task” at Amway was not sales but the recruitment of new IBOs to pay Amway more fees and buy more products.

For California businesses, 2020 will be a year of reckoning. Sweeping new laws curbing long-time employment practices take effect, aimed at reducing economic inequality and giving workers more power in their jobs.

“Amway told me that being a so-called Independent Business Owner would give me a chance to be an entrepreneur and grow my own business — but instead I spent hours every month trying to grow theirs,” Orage said in an emailed statement.

Amway didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. It has touted itself as the “world’s largest direct selling company,” with $8.8 billion in sales and more than a million “Amway Business Owners” in its network. It was co-founded by the late Richard DeVos, the billionaire conservative activist and father-in-law of U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Its current co-chairman is his son Doug DeVos.

According to Orage’s lawsuit, Amway is heavily focused on recruiting new distributors because of the sign-up and annual renewal fees they pay. IBOs are incentivized to bring in new ones because they receive a premium on Amway products purchased by their recruits. Orage claims the company closely controls the sponsorship process, encouraging IBOs to attend numerous trainings and coaching sessions, and its heavy involvement means IBOs should be treated as employees under California law.

Orage, who left Amway in 2019, says he made only two product sales during his four years with the company and alleges that he received no pay for the time he spent in training and trying, ultimately without success, to recruit new IBOs.

He filed his complaint under California’s Private Attorneys General Act, which also allows him to seek government penalties for thousands of Californians who’ve worked for the company. If successful, Orage and other affected workers will receive a share of the recoveries. He’s backed in the case by the legal nonprofits Towards Justice and Justice Catalyst Law.

Orage’s lawsuit is far from the first legal challenge to Amway’s business model. In 1979, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission found the company had fixed prices and overstated profitability, but decided it wasn’t an illegal pyramid scheme. In 2010, a former Amway subsidiary agreed to settle a suit alleging it ran a fraudulent pyramid scheme for an estimated $155 million.

California companies are scrambling to figure out how AB 5, a sweeping new hiring law, affects them.

California’s definition of who qualifies as an employee was broadened in a 2018 ruling by the state’s highest court. A law codifying that decision took effect Jan. 1 and is aimed at securing protections for gig workers.

“Amway has been using the ‘gig economy’ business model of using massive numbers of revenue-producing workers that are classified as independent contractors,” Brian Shearer, an attorney for Orage, said in an interview. “And they’ve been doing it for 60 years.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.