Smokers are left in the cold in states that allow businesses to not hire them

- Share via

Nearly a decade after she stopped smoking, Mabel Battle still has the last pack of cigarettes she ever bought. She keeps it as a reminder of all the gray Ohio winter workdays she spent standing outside her office with the other shivering smokers getting a nicotine fix.

The cigarette pack, still sealed in its original cellophane, is a testament to her willpower, she says: after countless failed attempts, she finally quit.

However, her success at giving up is also a striking result of a contentious corporate experiment. What finally prodded her into her decision was a fear that her habit might threaten her employment. “I wanted to keep my job more than I wanted to smoke cigarettes,” Battle says.

The Cleveland Clinic, where Battle works as a health unit coordinator, has been a leader in corporate anti-smoking initiatives. It first banned smoking on its 170-acre campus in 2008, and followed that up with a new policy to chemically screen job applicants for nicotine and refuse employment to those who test positive. Workers such as Battle who were on staff before the ban would not be fired for smoking in their free time, but she could see the culture changing.

When Rye Electric was founded in Orange County five years ago, it screened all prospective workers for drugs.

“Being a healthcare worker is setting an example,” says Dr. Bruce Rogen, the chief medical officer of the Cleveland Clinic’s employee health plan. Since the clinic instituted the ban and started offering free smoking-cessation programs to employees, Rogen says, hundreds of people at the clinic have quit.

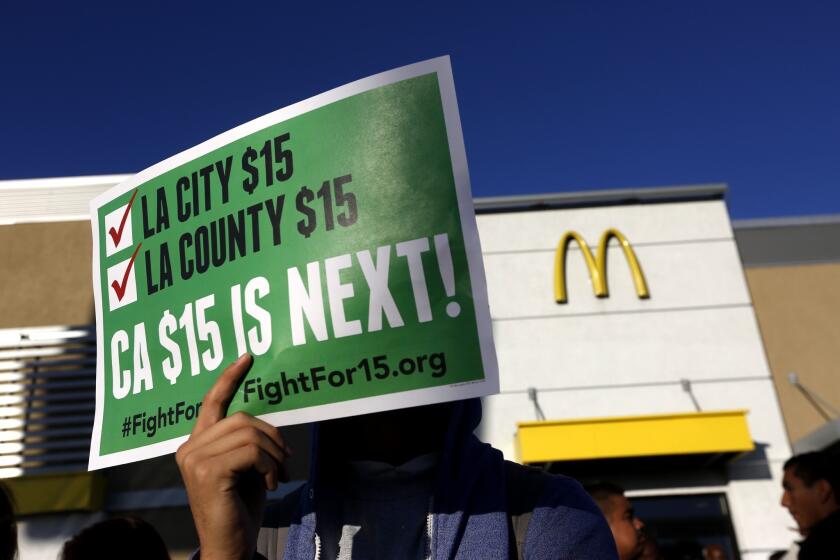

Only 21 states (including Ohio, where the clinic is based) allow companies to exclude smokers from their workforce outright. California is not one of them. And in those states this sort of policy has become the norm in the healthcare sector, Rogen says. Now the practice is spreading, and companies in other industries are implementing similar policies.

This delights anti-smoking activists. However, it has led civil liberties advocates to sound alarms about employers’ creeping control over workers’ lives even when they are off the clock.

U-Haul, the Arizona moving company with about 30,000 workers, this month became one of the country’s largest employers to stop hiring nicotine users — a term that includes not just smokers but users of “nicotine products.” This potentially covers people who test positive for nicotine because they are trying to give up smoking using vaping, gum or patches.

Like the Cleveland Clinic, U-Haul will allow those hired before the restriction to keep their jobs. The hiring ban will apply only in the same 21 states, and not in California.

However, should a company choose to fire any workers who use nicotine, the employees would have little recourse, depending on where they work. Smokers are not a “protected class” safeguarded by federal law, such as racial minorities or people with disabilities. That means in “at-will” employment states, a capricious boss can fire an employee for practically any reason, whether that is smoking off-duty or something as arbitrary as wearing the wrong color shirt to work.

“How far do the employer’s rights [to fire someone] go? It’s pretty much fair game unless the state prohibits it,” says Cathleen Scott, a Florida employment lawyer. “[A worker’s] choice is to take it or leave — that’s how it works in an ‘at-will’ employer environment.”

For California businesses, 2020 will be a year of reckoning. Sweeping new laws curbing long-time employment practices take effect, aimed at reducing economic inequality and giving workers more power in their jobs.

The states that do not allow companies to ban nicotine users often have laws that prohibit discrimination against “legal off-duty conduct,” says Karen Buesing, an employment law specialist at Akerman. But the extent of the protections offered by these laws can vary, and there is a lot of debate around cases of employees who have been fired for legally using medical marijuana.

Only a handful of employment cases over off-duty nicotine use have made it to court, but employment lawyers believe there could be ways to get these bans made illegal.

Off-duty “smoking bans have not been litigated sufficiently for the public to have a grasp as to whether [they are] enforceable,” says Daniel Gwinn, an employment lawyer in Michigan. “It seems interesting to me that you can be grossly obese, which is a lifestyle issue, and you can get protection [under U.S. labor law] ... but you can’t get protection for smoking.”

As for U-Haul, the company says its new anti-nicotine policy is part of its commitment to employee “wellness,” but there are also clear financial motives at work. When health insurance is provided by employers, companies pay more for health coverage if their workforce includes a lot of smokers, Buesing says.

About one in every four companies with more than 500 employees offers nonsmokers a reduced rate on their healthcare premiums, says Steven Noeldner, partner at consultancy Mercer.

Yet off-duty smoking bans are only one type of potentially invasive “wellness” program offered by companies. “Fitness contests” are growing increasingly common, where employees use step-counters or other tracking devices to prove how active they are in exchange for a discount on their health insurance.

These programs are perfectly legal, as long as they are structured correctly, but companies can get into trouble if the devices they use track more than just employees’ steps, Buesing says.

Most companies use third-party services to aggregate and anonymize the data they collect from these wellness initiatives to try to avoid this issue. But many companies are implementing even more intrusive programs — such as tracking workers’ locations via company-issued mobile phones.

“Technology is creating new ways to track and monitor employees,” says Brian Kropp, chief of human resources research at Gartner, a technology consultancy. Companies often scrape employees’ web-browsing history and monitor what they write and say on company equipment, he says. Others go even further, turning on workers’ webcams and using facial recognition software to gauge their sentiment about their jobs.

“The relationship between employees and employers is changing,” he says. Companies and their staff used to be “basically strangers” after the workday ended, but that is no longer the way things are.

As with off-duty smoking bans, lawyers say the legal landscape on electronic surveillance is still evolving. Complaints around these issues often settle out of court — such as a 2015 lawsuit brought by Myrna Arias, a saleswoman who was fired for turning off the GPS on her company phone while off duty.

“What companies are truly struggling with . . . is that they have not thought through the ethical [ramifications of their] decisions,” says Kropp. U-Haul’s management is decreasing its health insurance costs, but it is also making a statement about what the company believes are appropriate behaviors, he says.

These practices do not typically go down well with workers’ rights advocates.

“There was a time when employers used to make sure their employees went to church and didn’t drink. ... Mine operators would inspect people’s homes,” says Dale Ewart, who heads the Florida operations of labor union 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East. “No one wants to live like that. Your off-the-job behavior should have no bearing on your employment.”

California employers may dislike the new law on independent contractors, but they’re devising a host of strategies to comply.

Still, Gartner’s research shows a growing level of acquiescence to employer surveillance.

“A couple of years ago the perception was, ‘This is so Big Brother,’” Kropp says. But thanks to the growth of digital surveillance in people’s day-to-day lives by companies such as Amazon and Facebook, that view is changing. “If employees know the employer is collecting data and they know what it’s being used for, and it’s being used for something helpful, they are OK with it,” he says.

And this can also be the case with smoking bans. Battle, from the Cleveland Clinic, initially held a negative view of her company’s smoking policy. “When they first started it, I felt like [it was discriminatory],” she says.

Eight years later, she feels differently. “After I quit, I was glad they did it,” she says. “I am happy those cigarettes are out of my life.”

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.