Column: That blockbuster GDP number doesn’t give Trump grounds for bragging. Here’s why

It was always likely that the figure for economic growth in the third quarter of 2020, announced Thursday, would be huge.

It was also certain that the gross domestic product statistic would garner an immense amount of public attention, given that it’s the last economic estimate to be released before Tuesday’s election, and previous quarterly estimates have been so dismal.

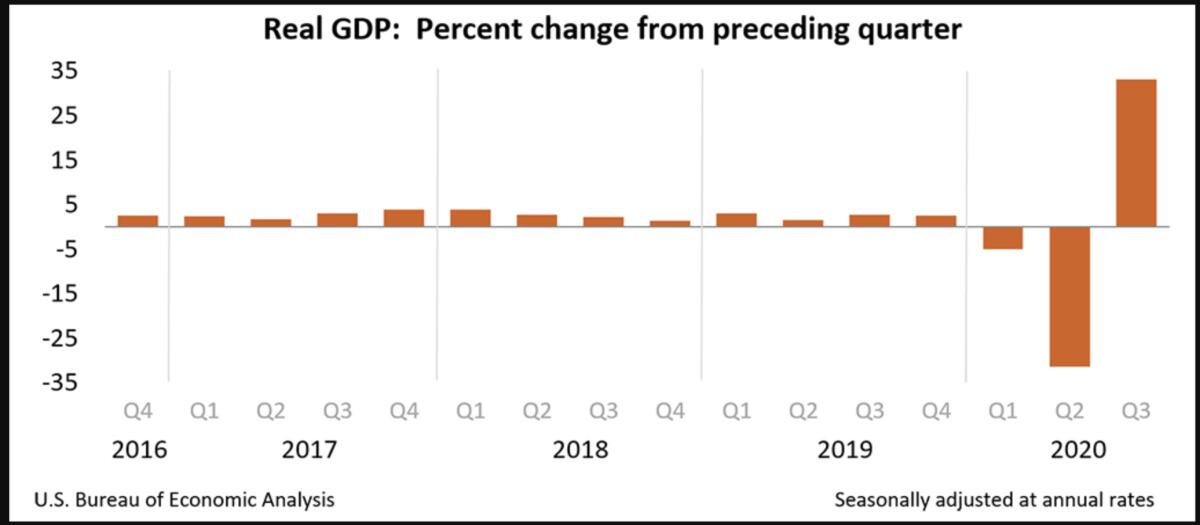

True on both counts. The Bureau of Economic Analysis placed its preliminary estimate of the annualized rate of growth for the third quarter, which ended Sept. 30, at 33.1%. That’s a historic figure.

We are in danger of falling into a deep hole again.

— Ian Shepherdson, Pantheon Macroeconomics

President Trump and his acolytes are sure to be out in force Thursday, declaring the number to be certification of the wisdom of Trump’s economic policies.

Trump took out advance advertisements on Facebook even before the release, according to the Financial Times, bragging that the GDP number would be “the highest in American history.”

He should put a sock in it. Here’s why.

First, the headline number of 33.1% is intrinsically misleading — it’s an annualized rate, meaning that it’s how fast the economy would grow if the actual third-quarter figures were extended out to a whole year. In truth, the economy grew by only 7.4% in the third quarter.

Moreover, either way you take it — whether as an annualized rate or the actual GDP change for the quarter — it must be considered in the context of previous changes in the size of the economy.

With the political world deeply focused on the question of whether the Trump administration comprises a gang of Russian pawns, less attention has been devoted to more mundane questions, such as what ever happened to Trump’s economic policy?

In the second quarter, which ended June 30, the U.S. economy was reported to have shrunk by a historic 9.46% (or 31.4% on an annualized basis). So Thursday’s 7.4% still doesn’t bring us back to where the economy was before the pandemic struck.

“All told, the economy is -3.5% smaller than it was at the end of 2019,” economist Justin Wolpers of the University of Michigan tweeted. “The economy is roughly as far below its peak as in the darkest days of the last recession.”

The explanation can be found in simple math because the percentage gain is calculated from a smaller base than the previous percentage loss.

Think of it this way: If you start with $100 and lose 10%, you end up with $90. Recovering 10% from there gets you to only $99. To get back to the full $100 you started with, you’d have to recover by more than 11.1%.

In this case, to recover the entire economic shrinkage of the first half of 2020, annualized third-quarter growth would have had to be 53.3%, calculated Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

One other mathematical wrinkle: The Bureau of Economic Analysis’ quarterly figures don’t exactly measure economic growth during the quarter. They’re the product of a complicated formula that takes into account economic growth over five months, starting in the final two months of the previous quarter.

The formula gives the greatest weight to the first month of the quarter, slightly less weight to both the second month of the quarter and the third month of the previous quarter, and slightly less weight again to the third month of the quarter being measured and the second month of the previous quarter.

(For math aficionados, here’s the actual formula, courtesy of Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist now working as a consultant:

4/3*g(-2)+8/3*g(-1)+12/3*g(0)+8/3*g(+1)+4/3*g(+2), where g(0) is the first month of the quarter.)

This means that growth in May and June this year gave a push to the growth figure for the July-to-September quarter. That’s important because the economy in May and June began to recover somewhat from its dizzying collapse in February, March and April.

The reasons were that the lockdowns of the winter and early spring began to be relieved in May and June, and also because stimulus programs enacted by Congress in March began to fill the pockets of American workers in those latter two months.

Those programs included an enhanced unemployment benefit, and a check of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child distributed to most households.

Those programs have since expired, and any further stimulus has been blocked by Senate Republicans, who decamped from Washington this week. They won’t be back until mid-November.

As a result, the economy is showing severe signs of stagnation, with no relief in sight until as late as next January. In other words, if one takes Thursday’s statistic as a snapshot of the economy, it’s a snapshot that has already faded.

Trump’s economy has been great for stock investors, but not for workers.

“To look at this more substantively, what these numbers tell you is fiscal policy works,” Shepherdson told Politico. “The federal government borrowed a ton of money and sent it out to individuals and businesses and it worked. Now we don’t have those things, and the expectation is growth will be much weaker in the fourth quarter and the virus picture is already much worse. We are in danger of falling into a deep hole again.”

Adding to the economic uneasiness is the largely uncontrolled surge of COVID-19 in most of the country, reflecting the all but complete abandonment of anti-pandemic efforts by the Trump administration.

One further question about the U.S. economy is a perennial one, highlighted by the pandemic: Whose economy is it? What seems to be emerging is a dreaded “K-shaped” recovery, in which the fortunes of the affluent remain on the rise but the ability of the middle and working classes to make ends meet is deteriorating.

This is a harbinger of further economic stagnation, as the average consumer runs out of money for staples, not to mention discretionary purchases. Nero is famed for fiddling while Rome burned, but he had nothing on a Senate and White House that haven’t even started looking for a fire hose.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.