Trump utterly failed to cut drug prices. Here’s how Biden could do better

- Share via

As a sort of sour welcome for the Biden administration and a final slap in the face for Donald Trump, America’s drug companies jacked up prices on hundreds of prescription drugs, including some of their top sellers, at the very start of this year.

Market analysts say the median price hike was 4.8%, a tad below last year’s level, but once you’ve said that you’ve said everything.

The increase levied by AbbVie on its rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira, the best-selling drug in the world, was 7.4%. AbbVie collects revenue of about $20 billion a year from Humira, though its patent exclusivity on the drug expires in 2023. Pfizer’s increase on its statin Lipitor was 4.9%.

This has been a rhetorical success but a practical failure.

— Rachel Sachs, Washington University in St. Louis

The drug industry’s semiannual price hikes, of which this month’s was merely the latest, have made a mockery of the Trump administration’s claim to have brought prescription prices down.

That’s not to say that anyone familiar with the industry ever took these claims seriously. Trump’s approach to drug prices has been, from the inception, all talk and no action.

“This has been a rhetorical success but a practical failure,” says Rachel Sachs, an expert on food and drug regulation at Washington University in St. Louis.

Trump’s failure leaves the path to controlling prescription drug prices wide open for President Biden, who delivered a regulatory wish list on the topic as part of his healthcare plank during his presidential campaign.

Biden also has a useful template to work with in the form of HR 3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act, which was passed by the Democratic-controlled House in December 2019 and stifled by the Republican-controlled Senate. With the Senate now under Democratic control, the Cummings Act has a solid chance of enactment.

Before we describe the Biden and House plans, let’s take a look at the abject failure of Trump’s policies.

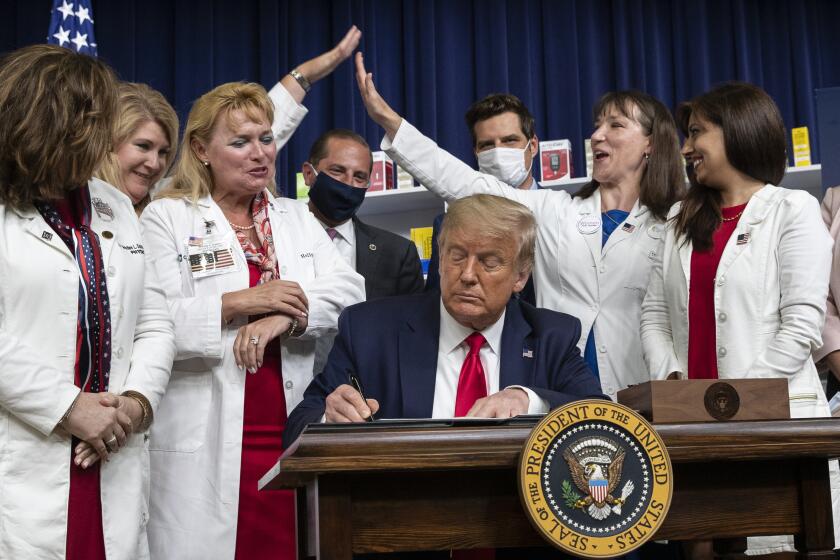

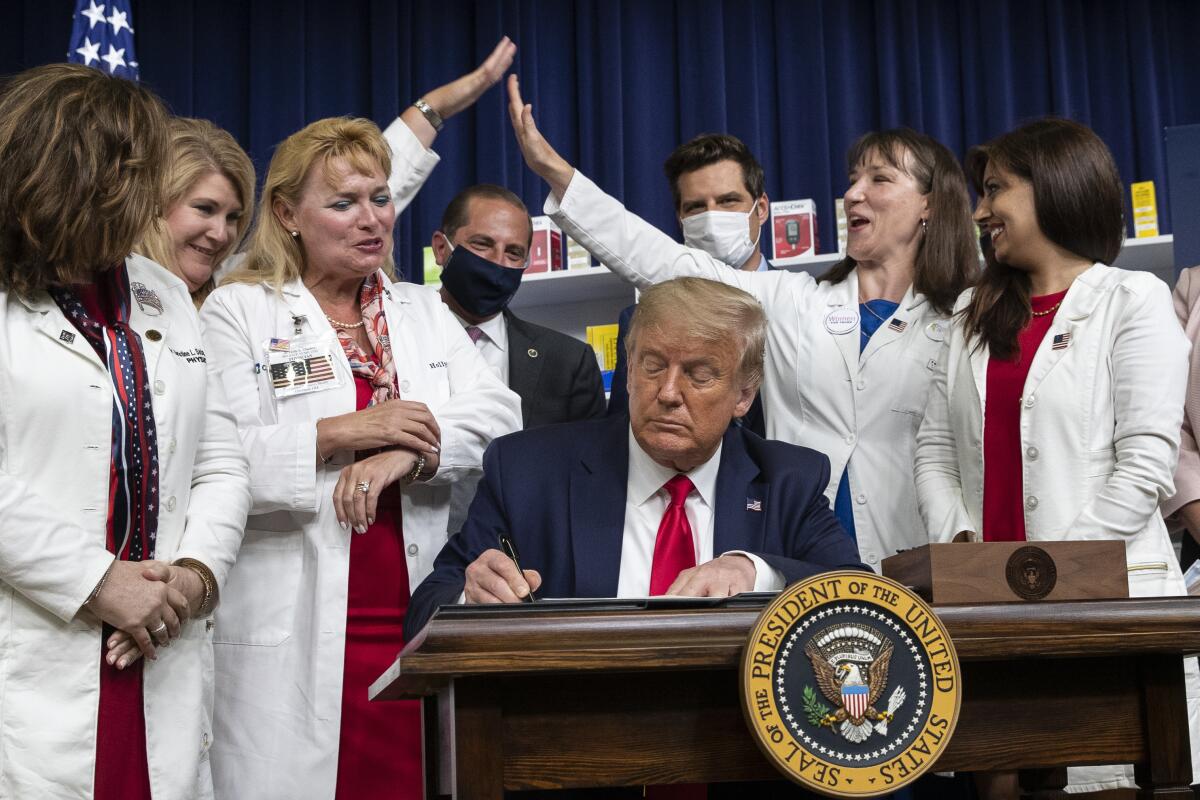

As Sachs observes, Trump was not shy about touting his (nonexistent) success at bringing down drug prices. “I’m really doing it,” he claimed in his opening speech at the Republican National Convention in August. “Your numbers are going to come down 60, 70%.”

The giant drug company Pfizer seemed to hand President Trump a big win Tuesday when it announced it would roll back a slate of price increases that took effect July 1.

Trump was specifically referring to executive orders issued in July. There were two key orders: One aimed to alter the system of drug rebates drugmakers paid to middlemen, which had the effect of propping up out-of-pocket costs to consumers. The second tied U.S. prices to those paid in other developed countries, known as granting the U.S. so-called most-favored-nation status in the worldwide pharmaceutical market.

As was typical of the Trump administration, the implementation of these proposals was hopelessly inept and confused. They were not even made final until Nov. 20, after Trump had already become a lame duck.

The proposals were vulnerable to legal challenges, which promptly appeared. A federal judge, ruling in a lawsuit brought by PhRMA, the drug industry’s lobbying arm, blocked the most-favored-nation rule on Dec. 23, one week before it was to go into effect. She ruled that the administration had not given the public a chance to comment on the proposal, as required by federal law.

The rebate proposal was challenged in federal court earlier this month by the Pharmaceutical Care Management Assn., which represents drug middlemen such as pharmacy benefit managers. The group’s lawsuit calls the rebate rule “the product of an erratic and highly irregular administrative process,” which is indisputable.

The lawsuit cited credible analyses by the Congressional Budget Office and Medicare and Medicaid actuaries finding that the rule would raise federal spending by an estimated $177 billion over 10 years, raise Medicare premiums for enrollees — and even increase drug company profits.

Fakery on this scale was a characteristic of drug pricing initiatives throughout Trump’s term. In mid-2018, he touted announcements by Pfizer and other drug companies that they were rolling back price increases, ostensibly due to his cajoling and jawboning. “Great news for the American people,” Trump proclaimed in taking credit for the Pfizer action.

In truth, Pfizer’s “rollback” was nothing of the kind. The company said it was merely deferring its price increases — its second round of hikes that year — and made clear the deferral was temporary and would be lifted no later than the end of the year.

It’s hard to believe that anyone was taken in this summer when a handful of drug companies announced rollbacks of price increases or price freezes on some of their drugs, ostensibly in response to jawboning by President Trump.

But both parties to this sham negotiation got what they wanted: Trump got to claim victory over Big Pharma, and Big Pharma was able to mollify Trump without actually giving anything up. In early December 2018, Pfizer and Merck, another big drug company that had claimed to be bowing to Trump, reinstated their increases.

That brings us back to Biden’s opportunities. Regarding the most-favored-nation and rebate proposals, Sachs gives the Trump White House credit for having “succeeded in normalizing the ideas behind both of these rules,” even if its ham-handed treatment of the administrative requirements and its delays in making the rules final hobbled their chances of success.

“Even if most rank-and-file Republican members of Congress did not support the most-favored-nations rule in particular,” she told me, “the idea now has prominent backing in both the Republican and Democratic parties.”

Indeed, the concept is embedded in the Cummings Act, which would mandate the use of an international price index as a benchmark for the government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare and Medicaid. Those negotiated prices could then be used by private insurers.

The act would also allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers for the first time. This has been a popular idea for years, but its potential effectiveness has been limited by another rule requiring Medicare and Medicaid to offer enrollees access to any drug approved for sale by the Food and Drug Administration. Without the right to walk away from the negotiating table, the government had little leverage to force price caps on manufacturers.

Despite Trump’s claims, prescription drug prices are still rising.

The Cummings Act would get around that problem by imposing an excise tax on any manufacturer that fails to reach price agreements with the Department of Health and Human Services. The levy would be a stiff one — starting at 65% of the total sales of the drug in question and rising steeply to 95% over three calendar quarters.

The act also would restrict price increases in Medicare parts D (outpatient prescriptions) and B (drugs administered in a doctor’s office) to the rate of inflation.

Biden’s campaign platform also called for limiting launch prices for new drugs brought to market without competition. Many such specialty drugs carry stratospheric price tags.

Biden proposed establishing an independent review board to assess their value and, if possible, peg them to the price in other countries. The result would be the price paid by Medicare and the public option plan Biden proposes for the Affordable Care Act marketplace. That would set a target price for private insurers, too.

Biden also proposed limiting drugmakers’ ability to game the generic market, a practice that enables them to effectively extend their exclusive marketing of brand-name products even after their patents expire.

As Sachs points out, healthcare reform is always a question of trade-offs. In the case of pharmaceuticals, limiting the potential profits for manufacturers might lead to less research and fewer new drugs reaching the market, in exchange for more access for consumers to existing drugs. Some options might require higher spending by government programs.

At some level, drug price regulation can seem simple. Trump exploited that phenomenon. “The idea behind the rebate and most-favor-nation rules were very easy to understand,” Sachs says. “People understand the idea that middlemen are keeping their money and they’re paying higher prices at the pharmacy counter because of it. And they understand that we pay much more than other countries for the same drug.

“But the difficulties are in the implementation and the trade-offs.” Those are the shoals on which the Trump drug price ship crashed. Knowing where the dangers lie, Biden and the Democratic Congress may finally be able to reach harbor.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.