Chipotle says it raised prices to cover hourly wage hike, doesn’t mention execs’ huge COVID-19 bonuses

- Share via

Fans of Chipotle Mexican Grill’s burritos and tacos got a dose of bad news recently: The company will be raising the prices of its fast food menu by as much as 4%, or a whopping 30-cents-plus on the sub-$8 price of a chicken-based meal.

To hear executives at Newport Beach-based Chipotle talk about it, the increase was forced upon them by the cost of front-line labor.

At a recent investors conference, they described workers’ wages as the main “inflation pressures” they and their competitors in fast food are feeling just now.

Chicken bowl, brown rice, black and pinto beans, pico, hot salsa, lettuce, cheese, sour cream — that’s all I want. And I want it for $7.60 plus tax.

— Kylee Zempel, The Federalist

Higher wages and recruitment bonuses are necessary to attract the 20,000 workers needed for the 200 locations it plans to open this year, Chipotle says.

Conservatives assigned blame almost immediately. “The federal government is the cause,” wrote Kylee Zempel of the Federalist, a right-wing website.

“Chicken bowl, brown rice, black and pinto beans, pico, hot salsa, lettuce, cheese, sour cream — that’s all I want,” Zempel wrote last week. “And I want it for $7.60 plus tax. Thanks to the ill-named American Rescue Plan and remarkably short-sighted employment decisions, the federal government has jacked up the price of my Chipotle order.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

We yield to nobody in admiring the skill of the Federalist and its leadership at getting their hands around the wrong end of the stick. In this case, they missed a few pertinent facts.

That’s not entirely surprising because Chipotle did its best to obscure the financial factors that have contributed heavily to what the company breezily describes as “inflation pressures.”

Among the factors unmentioned by Chipotle is executive pay, which soared in 2020, even as profits in the pandemic year stagnated at $356 million on revenue of $5.9 billion, compared with $350 million on revenue of $5.6 billion the year before.

Hiltzik: Employers say lavish unemployment checks make it hard to hire workers. Don’t believe it

Restaurants say people are refusing to work because unemployment benefits are so good. You should be skeptical.

Let’s take a look.

To begin with, Chipotle’s announcement of its wage increase seems designed to sow misunderstanding. The headline on its May 10 press release states “Chipotle Increases Wages Resulting in $15 per Hour Average Wage.”

If you thought that meant the company is setting its minimum wage at $15 an hour, you’re wrong. Read farther down, and you discover that hourly workers will receive “starting wages ranging from $11-$18” by the end of this month.

That leaves the effect of the wage increase on Chipotle’s bottom line unclear. Chief Financial Officer Jack Hartung in April told investment analysts that the average wage for all hourly employees was $13, which implies a 15% increase in the hourly payroll to reach $15.

At the time, Hartung said that could be managed with a 2% to 3% price increase. But at the June 8 investors conference, he said Chipotle’s strategy was “to get in front of this and lead,” which implies that it’s raising prices at least a tad more than it needed just to cover the wage raise.

Chief Executive Brian Niccol said at that session that Chipotle feels it has plenty of latitude to pass expenses on to consumers. “We have a really strong value proposition with more pricing power if we had to pull that lever,” he said.

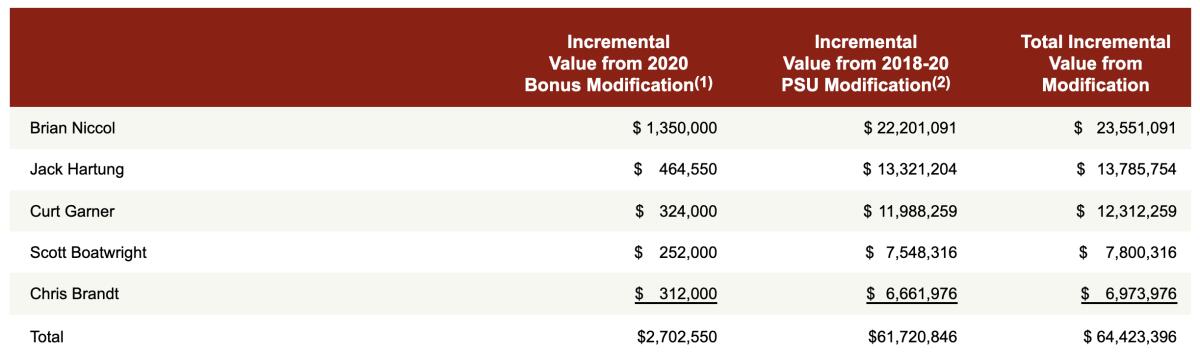

Chipotle’s description of its executive compensation in 2020 is also rather convoluted. In its financial disclosures to shareholders, the company reported that it awarded its top five executives a total of $64.4 million in “modifications” of their stock-related compensation. That compensation is based on improvements in the company’s cash flow and other financial metrics.

Evidence mounts that some employers can’t find workers because they’re jerks.

As the company explained the change, it removed the three months in which the pandemic most severely affected its results from the calculation of cash flow, excluded some pandemic-related expenses from the calculation and reduced the threshold financial improvement necessary to trigger the stock grants.

These changes may seem modest, but their effect on the executives’ compensation was immense. The result was a more than doubling of Niccol’s pay to $38 million from $16.1 million in 2019; without the recalibration, he would have suffered a pay cut to $14.8 million.

Hartung and the company’s chief technology, restaurant and marketing officers also would have incurred pay cuts were they not rescued by the change.

One could argue that since most of the executives’ compensation comes in the form of stock grants that are paid out over time, these numbers don’t flow to Chipotle’s annual bottom line as directly as hourly pay.

But Chipotle will have to pay these sums sooner or later (assuming they’re earned through performance), so the money will have to come from somewhere. Hartung told investors last week that the company is determined to maintain the financial returns from its restaurants, which he said range from 40% to 70% per location.

There’s one other factor in Chipotle’s expenses that warrants mention. That’s the cost of relocating its headquarters to Southern California, which involves giving up office leases in Denver and moving staff from there and New York City. That was done at the behest of Niccol, who had been a top executive of Taco Bell and made it a condition of his accepting the CEO post at Chipotle. The company has estimated the cost of the move at up to $80 million.

To put it another way, conservatives grouse about low-wage workers having to be “bribed” into going to work, but they’re silent on high-wage CEOs having to be bribed even more lavishly.

Put it all together, and it becomes clear that numerous factors went into Chipotle’s decision to raise prices. To conservatives, however, one factor is enough to tell the story: the purportedly lavish unemployment pay Congress awarded slackers to stay at home instead of working.

“Restaurants have had to bribe current and prospective workers with fatter paychecks to lure them off their backsides and back to work,” Zempel of the Federalist wrote. “That’s what happens when the federal government steps in with a sweet unemployment deal, incentivizing workers [to] do a little less labor and a little more lounging.”

Zempel deserves some credit, one supposes, for saying the quiet parts out loud by showing what she thinks about the people who prepare her cheap meal: She writes of Chipotle’s “dangling a $15-an-hour wage in front of the low-skill teens who work there,” with the consequence that after paying that extra dime or quarter or buck an hour, “the franchise will stuff that extra cost right into your burrito.”

Chipotle Mexican Grill provided its new chief executive, Brian Niccol, with the usual blandishments when it recruited him from Taco Bell back in February, including $3 million in guaranteed salary and bonus, another $1-million bonus upfront and $5 million in stock-based incentives.

(The Federalist has a sterling conservative pedigree: It was founded by Ben Domenech, whose father, Douglas, was a top official in the George W. Bush and Trump administrations, and whose wife is Meghan McCain, daughter of the late Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona.)

Zempel’s post links to a hand-wringing 2020 analysis by the right-wing Heritage Foundation complaining that what was then a $600 weekly federally funded increase in unemployment benefits would cause “higher levels of unemployment claims and longer durations of unemployment, which translate into lost goods and services.”

Never mind that the purpose of the increase was to protect workers from the cost of staying home, whether because government orders required the employers to close up shop or because their businesses had suffered because customers were staying away of their own accord.

Some red-state governors have even canceled the enhanced unemployment benefits on the reasoning that doing so will get layabouts back to work.

In fact, there’s precious little evidence that workers are giving the cold shoulder to good jobs because they can earn more from unemployment. The evidence suggests, instead, that they’re giving the cold shoulder to lousy jobs, including those offered by employers who haven’t shown that they care much about their employees’ health and safety. These are the employers who post signs advising customers that wait times are longer because “nobody wants to work.”

As numerous employers — including Chipotle — have found, people will work if you offer them a decent wage.

Now that the federal increase has been cut to $300 a week and will expire anyway the first week of September, conservatives’ complaints have shifted to encompass the claim that the lavish benefits will end up costing average consumers by driving up prices at the cash register.

Will employers pass the costs on? Certainly some will. So what? Nothing in the law or social tradition says that consumers are entitled to goods or services at rock-bottom prices based on the exploitation of rank-and-file labor. Americans have become addicted to those prices because the factors keeping them low have been swept under the carpet. The pandemic has brought them into the daylight.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.