Column: The IRS wanted a new tool to go after tax cheats. Republicans and bankers blocked it

Here’s a handy rule for anyone struggling to decode policy debates in Washington: If the GOP is throwing a fit about something, you can be sure its complaints are bogus.

Latest case in point: a provision in the Build Back Better bill, the Biden administration’s omnibus spending package, that would give the Internal Revenue Service more of the information it needs to crack down on tax cheats.

The proposal would have required banks to report gross inflows and outflows in accounts with balances of more than $600 in a year and tighten reporting from online selling platforms such as Etsy and EBay.

High-income individuals in companies, either because of our tax laws or because they don’t accurately report their income, are able to evade their responsibilities.

— Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen

As depicted by congressional Republicans and their peanut gallery of right-wing commentators, the proposal would empower legions of gimlet-eyed IRS agents to poke their snouts into even your tiniest financial transactions.

Here’s House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield): “Democrats want to spy on anything you earn or buy that is more than $600. By hiring 85,000 new IRS agents to dig through every aspect of your life the Democrats want to enlist a bureaucratic army to achieve their goal of a big-government socialist nation.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.): “Washington liberals want to let the IRS leaf through Americans’ checking accounts as if everyone were a potential criminal or terrorist until proven otherwise. The IRS already knows how much you earn. Now they want to know exactly how you spend it.”

Right-wing pundit Candace Owens: “The Biden administration is attempting to empower the IRS to monitor every single withdrawal, deposit, and transaction you make from your personal banking accounts, PayPal, Venmo, etc.”

Not a single one of these assertions is true.

Nevertheless, congressional Democrats are bailing on the proposal. They’re considering changing the threshold for reporting to $10,000, which would give tax cheats sizable headroom to hide income. The proposal would also exempt inflows such as those from direct-deposited wages.

It was obvious almost from the inception of the ginned-up IRS “scandal” that its goal was to intimidate the agency into allowing bogus nonprofits to funnel cash into election campaigns.

Even that doesn’t satisfy the banking industry, which like all industries has never met a regulation it couldn’t describe as the end of civilization as we know it.

The revised plan will still raise “privacy concerns, increase tax-preparation costs for individuals and small businesses, and create significant operational challenges, particularly for community banks,” according to Rob Nichols, chief executive of the American Bankers Assn.

Given this volume of stuff and nonsense, it behooves us to clear the air by explaining what the original proposal actually would do and why it’s necessary, and to place it in the context of the long, discreditable history of attacks on the IRS by mouthpieces for the wealthy.

To make a long story short: The proposal wasn’t aimed at examining every little transaction in your bank account, and would not have accomplished that. It was aimed at the biggest tax cheats in the land: the 1%.

According to a study published by the IRS this year, this segment, comprising households with annual income of about $420,000 or more, hides as much as 21% of every dollar of income from tax collectors. Of the unreported income, about six percentage points is hidden by “sophisticated evasion that goes undetected in random audits,” the study found.

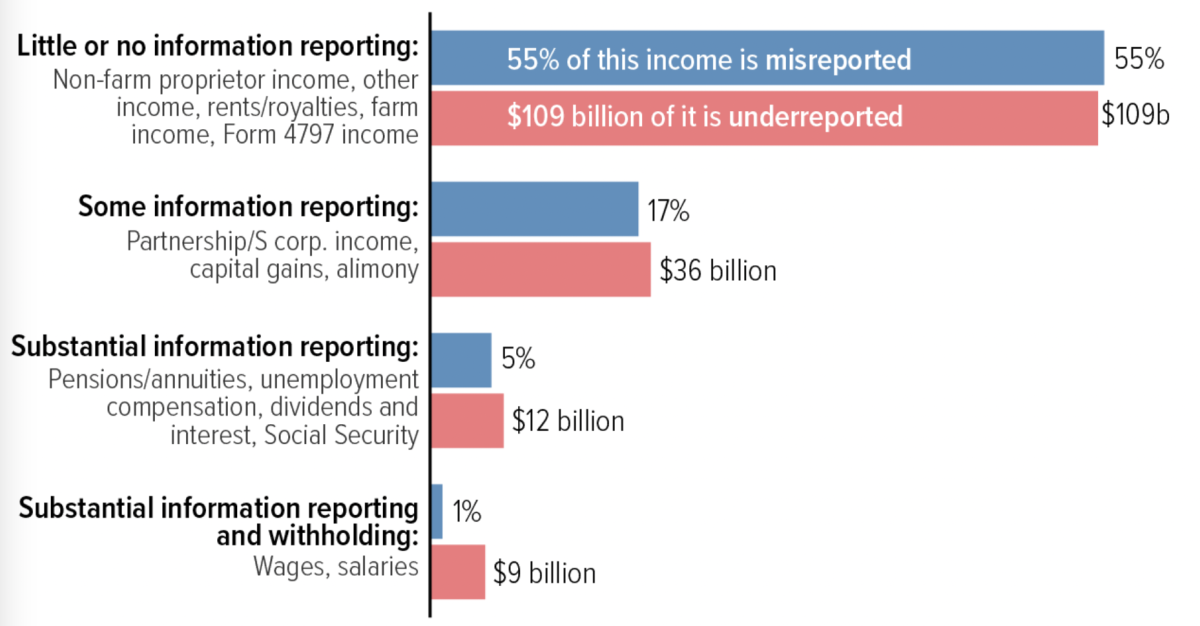

The evasion doesn’t have to be all that sophisticated. Much of it escapes IRS notice because it comes in a form that doesn’t have to be reported to the IRS by third parties. It’s partnership income, rent, capital gains and other income that’s up to the taxpayer to report; about 55% of this income is “misreported,” the IRS says.

That’s different from wages, which are reported by employers and therefore on which under- and nonreporting is minimal — only about 1%.

The result is a “tax gap,” as the IRS puts it, that reached $630 billion in 2019 — more than 2.5% or gross domestic product and about 17.5% of the more than $3.6 trillion owed.

Now let’s turn to the Biden proposal. The reporting requirement is part of a larger effort to rebuild an IRS that has been systematically starved of resources for decades, resulting in plummeting audit rates, especially of rich taxpayers or tax scofflaws.

Biden proposes adding $80 billion to the agency’s budget to upgrade its computer systems and add staff.

How bad is the audit record? As we reported last year, 23,456 U.S. households reported income of $10 million or more for the 2018 tax year, averaging more than $26 million each in taxable income. The IRS audited seven of them.

The Biden administration, following the recommendation of the Treasury Department, made the proposal that banks be required to report total inflows and outflows on accounts if the gross flows were more than $600 in a year or the accounts were valued at more than $600.

The goal, as Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told the Senate Finance Committee in June, was to collect “at least enough information to give a guide as to where the auditing resources should be used so that we do have fairer tax collections.”

The reports would merely have to specify how much of those inflows involved foreign bank accounts and how much came from or went to other accounts held by the same owner. No other breakdowns of individual transactions would be required beyond what’s already reportable.

The Treasury also intends to require those online selling platforms to report payments to their sellers of at least $600 starting next year, no matter how many transactions are involved, down from the current thresholds of $20,000 and 200 transactions. No one would be inconvenienced by this requirement other than those aiming to hide that income from the IRS.

So much for the heavy breathing coming from critics. Banks already have to tell the IRS of any interest payments made on individual or business accounts totaling more than $10 in a year.

Transactions such as mortgage payments, property tax installments and charitable donations are already reported by taxpayers taking itemized deductions.

It’s widely assumed that the biggest tax scofflaws are those with the most money. A new study tells us things are much worse than anyone suspected.

Some of the points raised against this proposal are so dishonest as to beggar belief. Let’s take a couple of examples.

Start with the banking industry’s “privacy concerns.” This must be some sort of a gag. The biggest threat to account holders’ privacy comes from the banks themselves.

In 2019, Capital One disclosed a data breach that potentially affected 100 million Americans. The bank assured the public that 99% of people’s Social Security numbers weren’t compromised, but that left 140,000 that may have been. In 2011, Citibank disclosed that the personal information of 360,000 of its credit card holders had been breached.

And let’s not forget Wells Fargo, whose own employees created 1.5 million fake accounts in customers’ names without their permission, sometimes draining legitimate accounts to create balances in the fake ones. The employees also applied for nearly 600,000 credit card accounts in customers’ names without permission.

In short, the bankers’ concerns about customer privacy would ring truer if the industry showed even a speck of concern for private data under its control. But it hasn’t.

As for the hand-wringing over the reporting burden on banks, Yellen explained to the Finance Committee that the IRS would collect “just a few additional pieces of information that will be simple for financial institutions to provide” — filling in two additional boxes on forms already sent to the agency, with information every bank already has in hand for every depositor.

Then there’s the grousing about this proposal “politicizing” the IRS. Here’s the Heritage Foundation’s Scott Zipperle: “The Internal Revenue Service — an already scandal-ridden and historically politicized government agency — could once again be weaponized against political opponents.”

Who “politicized” the IRS? The Republican Party, that’s who. Has everyone forgotten that dud of a “scandal” ginned up by the GOP in 2013 and 2014, when the GOP accused the IRS of targeting conservative nonprofit groups for special scrutiny?

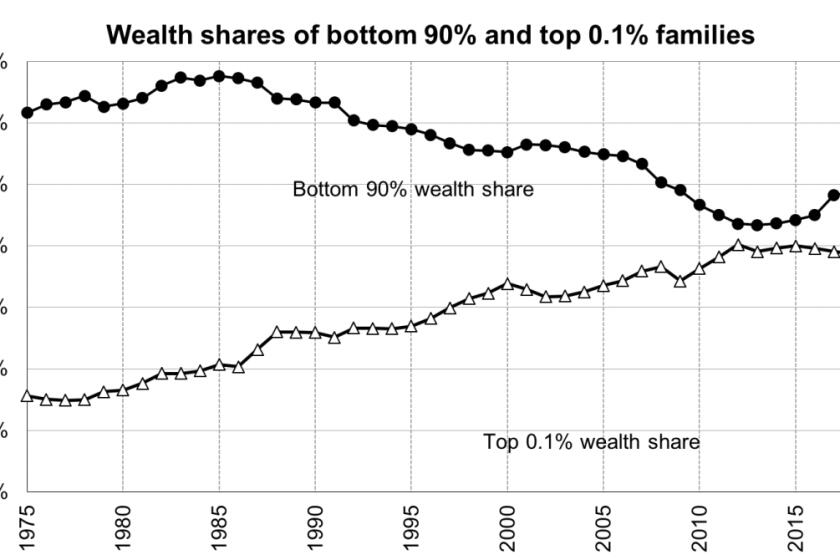

Why is economic inequality growing in America? Blame the lack of tax enforcement.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Bonsall), who spearheaded the investigation into this nonexistent targeting during his previous congressional term, eventually had to admit that he had been blowing smoke. The IRS had been looking into so-called C4 nonprofit groups to make sure they were complying with rules barring their engaging in politics.

As it turned out, only one C4 organization lost its tax exemption because of this scrutiny — the progressive group Emerge America, which trains Democratic women to run for office. No conservative groups lost their exemptions.

Issa’s investigation did serve its real purpose, which was to intimidate the IRS so it wouldn’t investigate political action groups masquerading as C4 social welfare organizations. In the wake of the uproar, the Center for Public Integrity found, “the IRS’ nonprofit division ... effectively lost whatever nerve it had left.”

So let’s not forget what really underlies all these complaints about the IRS — its depiction as a legion of jackbooted thugs determined to scrutinize your tiniest household bills and payments in search of innocent Americans to haul off to tax jail.

Fatuous nonsense. The critics’ purpose is to allow their wealthy patrons to continue to make out like bandits, at the expense of ordinary taxpayers who follow the law: “honest taxpayers who earn mainly wage income that’s accurately reported to the IRS,” Yellen said. They “feel that they’re not getting fair treatment because high-income individuals in companies, either because of our tax laws or because they don’t accurately report their income, are able to evade their responsibilities.”

She’s right. The original $600 threshold for reporting wouldn’t affect those honest taxpayers one bit, but it would have helped close the door on the truly guilty.

So now the Democrats have folded. The newly proposed threshold of $10,000 will leave the door open by more than a crack. Who will pay the price for giving tax cheats this break? You will.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.