The talk of raising a statue to Earl Warren would force a reckoning with his racist record

- Share via

The emerging debate over which Californian should replace the now-disdained Father Junípero Serra as one of the only two representatives of the state enshrined in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall has thrown up some intriguing names: Jackie Robinson, Cesar Chavez, Sally Ride and John Steinbeck among them.

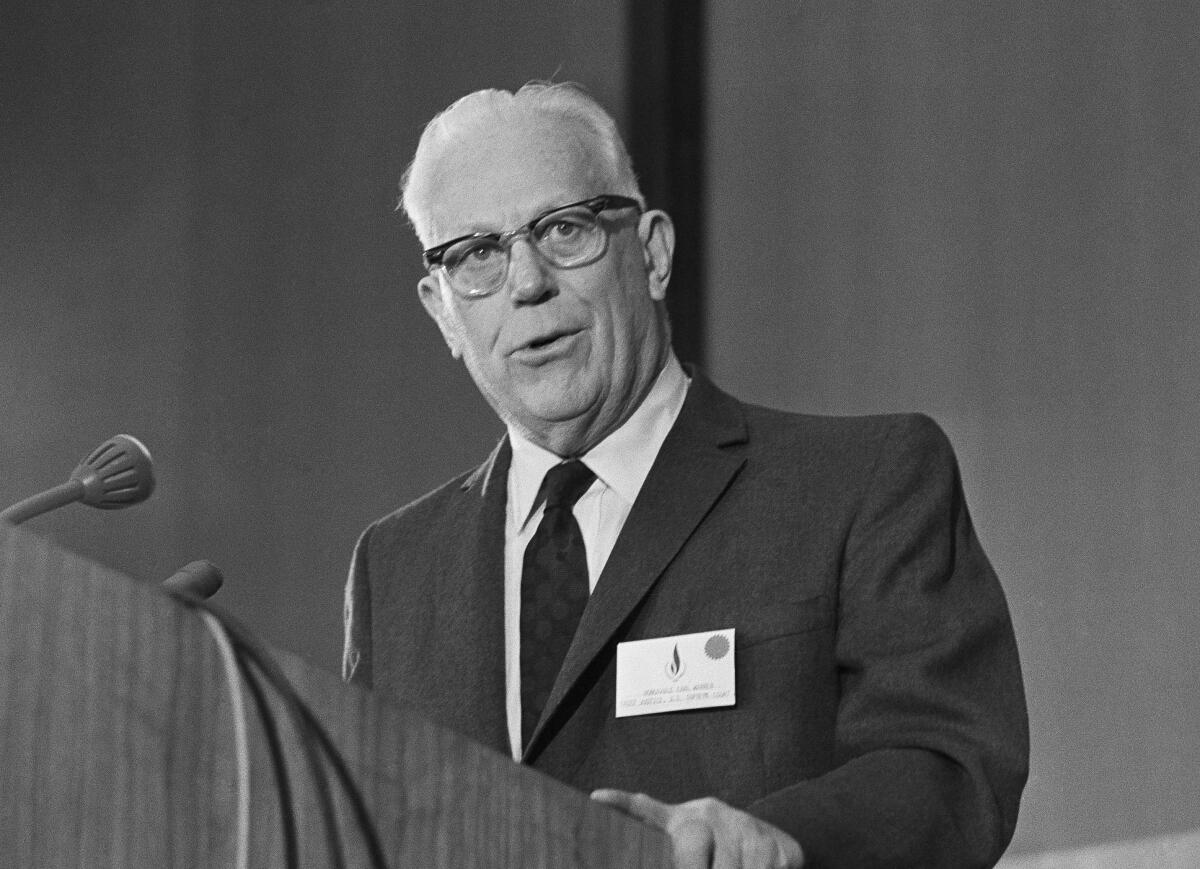

Also Earl Warren, a former governor of California who is regarded as a liberal icon for his record as chief justice of the U.S., especially for writing the unanimous 1954 Supreme Court opinion in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a cornerstone of the civil rights movement.

Warren’s legion of admirers might be well advised to hope the discussion doesn’t go any further.

I never apologize for a past act. That is just a matter of history now.

— Earl Warren, on his advocacy of wartime Japanese incarceration

That’s because it’s sure to force a public reckoning with Warren’s role in one of the darkest episodes in American history, the dehumanizing relocation and incarceration of more than 110,000 residents of Japanese extraction in California and other Western states during World War II. In any event, the reckoning is overdue.

Warren’s support of the dehumanizing treatment of Japanese residents came in 1942, while he was California attorney general; he would notch the first of his three gubernatorial election victories later that year, and was elevated to the high court by President Eisenhower in 1953.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As attorney general, however, Warren produced what must stand as one of the most irremediably racist presentations by a public official in 20th century American history.

This is his Feb. 21, 1942, testimony, before a congressional committee chaired in San Francisco by U.S. Rep. John H. Tolan, D-Oakland. Reading Warren’s testimony today, as I did while researching my forthcoming book, a history of California, will be a shattering experience for anyone accustomed to thinking of him as a hero of the campaign for equal protection under the law.

Before delving into the details, some background about the Statuary Hall issue. Serra’s reputation has plummeted since his statue was installed at the Capitol in 1931. (The other Californian in the hall, to which every state contributes two statues, is Ronald Reagan.) The law allows the statues to be replaced once a decade.

A Franciscan missionary from Spain, Serra was long lionized as a pioneering missionary spreading the Catholic faith during the Spanish colonization of the West Coast in the 18th century. In recent years, scholars have pointed to the abuse and effective enslavement of Native Americans at the missions he founded.

Pope Francis canonized Serra in 2015 as “evangelizer of the West,” even though reconsideration of the Serra legend had already become part of America’s confrontation with its historical racism.

California turned anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese sentiment into a national movement.

Warren’s support for the Japanese incarceration isn’t a secret. My colleagues on the Times Editorial Board cited it in passing in a recent piece about the Statuary Hall issue.

But such mentions fail to communicate the flavor of Warren’s testimony or the importance of his role. Indeed, it’s conceivable that without his support, the incarceration might never have taken place. That would have avoided the stain that the episode indelibly places on America’s moral standing.

Warren’s testimony to the Tolan committee is an extended accusation that Japanese residents, including American citizens, were effectively guilty of betraying and deceiving America. His remarks landed on fertile ground for paranoia, as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had occurred a little less than three months earlier.

In his presentation, Warren placed the most sinister possible interpretation on every nugget of information he presented; referring to the maps of Japanese landholdings throughout the state, he said that they showed “a disturbing situation. …[A]long the coast from Marin County to the Mexican border virtually every important strategic location and installation has one or more Japanese in its immediate vicinity.”

Warren suggested that this couldn’t be coincidental — the Japanese were in these locations to conduct surveillance and sabotage.

The truth was that the existence of many of these landholdings was the product of a historical injustice: Forbidden by California law to own land or to lease it for more than three years at a time, immigrant Japanese — the Issei generation — gravitated toward parcels disdained by those burdened by no such restrictions. Those were, in the later words of agricultural historian Masakazu Iwata, “thousands of acres of worthless lands … which the white man abhorred.”

Warren dismissed as immaterial the fact that no evidence had been found by the FBI or military authorities that any such surveillance, much less sabotage, had occurred.

“Many of our people and some of our authorities … are of the opinion that because we have had no sabotage and no fifth column activities in this State since the beginning of the war, that means that none have been planned for us.” But “that is the most ominous sign in our whole situation,” he testified. “I believe that we are just being lulled into a false sense of security and that the only reason we haven’t had a disaster in California is because it has been timed for a different date.”

Asked by a committee member whether it was possible to distinguish which of the U.S-born Japanese residents were loyal to the U.S. rather than to Japan, Warren opined that “there is no way. ... We believe that when we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them and we believe that we can, in dealing with the Germans and the Italians, arrive at some fairly sound conclusions because of our knowledge of the way they have in the community and have lived for many years. ... But when we deal with the Japanese we are in an entirely different field.”

Warren’s assertions about the faithlessness of Japanese residents drew upon a strain of anti-Japanese sentiment in California that dated back to the turn of the century.

They may also have reflected the desires of his supporters in the California farming industry, who had come to covet the lands that skillful Japanese farmers had brought to production. Federal agricultural officials watching the spreading campaign to evict Japanese residents from their lands saw it as the harvest of a “propaganda campaign” by white farmers aiming to “eliminate Japanese competition.”

Since Warren’s testimony came two days after President Franklin Roosevelt had issued his infamous Executive Order 9066 allowing Secretary of War Henry Stimson to designate any portions of the Western United States as “military areas … from which any or all persons may be excluded,” his defenders sometimes try to minimize his responsibility for the policy. Yet Roosevelt’s order, as indefensible as it might be, was a generalized grant of authority; nowhere in its five terse paragraphs do the words “Japanese” or “Japanese Americans” appear. At the time of Warren’s appearance, the scope and nature of the policy was just beginning to be hashed out.

Moreover, Warren had been assiduously filling the ears of political and media dignitaries visiting from out of state to weigh the security situation on the coast with alarmist visions of Japanese perfidy. One visitor was Walter Lippmann, a syndicated columnist who reigned as the preeminent political commentator in the land. After meeting with Warren, Lippmann produced a sensational column entitled “The Fifth Column on the Coast,” which was distributed to the more than 200 newspapers to which Lippmann’s work was syndicated, including The Times.

Caltech’s revered Robert Millikan favored forced sterilization. Can the university come to grips with its past?

“The Pacific Coast is in imminent danger of a combined attack from within and from without,” Lippmann wrote. “It is a fact that the Japanese navy has been reconnoitering the Pacific Coast more or less continually and for a considerable period of time, testing and feeling out the American defenses.”

It’s true that Warren’s role in the incarceration demonstrates that some of our most lauded heroes harbor human imperfections. It has even been argued that Warren’s remorse over his actions in 1942 set him on a path to personal redemption that culminated in Brown v. Board of Education.

But that won’t do. During his lifetime, Warren consistently refused to comment on his role in the Japanese incarceration, although he would often be asked to justify himself. One notable incident took place in April 1969, after Warren spoke at a human rights conference at UC Berkeley’s law school, his alma mater.

A delegation of 25 third-generation Japanese American students — that is, children and grandchildren of those who had been subjected to incarceration — asked him to publicly apologize for “his role in the mass denial of civil liberties to American citizens of Japanese ancestry,” in the words of an account in Pacific Citizen, a publication of the Japanese American Citizens League.

Warren refused. “I never apologize for a past act,” he responded uneasily. “That is just a matter of history now.”

The closest thing to an apology appeared only in Warren’s memoirs, published posthumously in 1977, three years after his death. “I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony regarding it,” the memoirs read, “because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens.”

Yet there’s reason to question whether these were entirely Warren’s words. As my former colleague Jim Newton reported in his authoritative 2006 biography of Warren, “Justice for All,” someone may have augmented Warren’s manuscript with the word “deeply.”

It’s proper to consider Warren as a representative of California values worthy of installation in the U.S. Capitol. But beware: In the bright fabric of California’s history, there are some very dark threads. Earl Warren’s life speaks to those too.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.