Letting Medicare negotiate drug prices won’t help as much as you think

- Share via

Americans have an enduring — and endearing — faith that one method of bringing down drug prices is superior to all others: Allowing Medicare to negotiate with drug companies.

The idea consistently polls well, supported by 83% of respondents to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey, including 95% of Democrats, 82% of independents and 71% of Republicans.

It addresses the No. 1 healthcare concern cited in public surveys, the high cost of prescription drugs, and accordingly has held pride of place among Democrats’ policy proposals.

Brand-name drugs are the primary driver of the higher prescription drug prices in the United States .... It’s just for the brand-name drugs that we pay through the nose.

— Andrew Mulcahy, Rand Corp.

Medicare accounts for about one-fifth of U.S. healthcare spending, but if it could set drug prices, those might become benchmarks for private health plans that account for about one-third of spending.

Sadly, the proponents’ faith is probably misplaced. Even the most aggressive proposals in the congressional hopper to allow Medicare negotiations could be gamed by drug companies.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Moreover, Medicare’s position as a negotiator would be undermined by another rule that isn’t under consideration in Congress: the legal mandate that the program offer enrollees access to any and all drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

That prevents Medicare from taking the most effective step to win negotiations with drug companies — the threat to walk away from the table. That’s what allows the Department of Veterans Affairs, the most accomplished drug price negotiator among federal agencies, to do as well as it does: It’s permitted to drop drugs from its formulary if it deems them too expensive or not sufficiently effective.

Congress is still grappling with measures to reduce drug prices. The most recent version of a Medicare negotiation measure, crafted by Senate Democrats and made public Tuesday, would allow negotiation on up to 30 drugs by 2028, according to Politico—fewer than would be subject to negotiation than in a long-standing Democratic proposal. And it gives drug companies more latitude to raise prices in general than reform advocates wish. On the plus side, it would limit out-of-pocket payments for insulin to $35 per dose and cap seniors’ maximum drug costs at $2,000 a year.

Reformers are already expressing disappointment: “A much stronger agreement should have been reached,” says Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen.

Foreign countries whose drug prices are often cited as possible benchmarks for U.S. healthcare payers don’t enter talks with one arm tied behind their backs — they can set prices based on measures of effectiveness, value and the cost of research and development.

Jane Blumenfeld isn’t sure when or how she contracted hepatitis C.

Healthcare programs in other countries also appear to be relatively immune from the mythologies purveyed by the drug industry to justify the sky-high prices in the United States, such as the claim that the industry needs uncapped prices to pay for research and development. Limit prices, the companies say, and innovation will suffer.

Yet as the Commonwealth Fund reported in 2019, that hasn’t happened in France, a particularly stern negotiator. France pays a premium for drugs that show a real improvement over existing treatments. That system “provides incentive to bring drugs to market that offer significant therapeutic improvement, rather than ‘me too’ drugs,” the Commonwealth Fund reported.

It’s fair to say that price caps would run into a political brick wall, largely thanks to the pharmaceutical industry’s lobbying clout. But the same influence will ensure that whatever negotiation rules are enacted are weak and easily gamed.

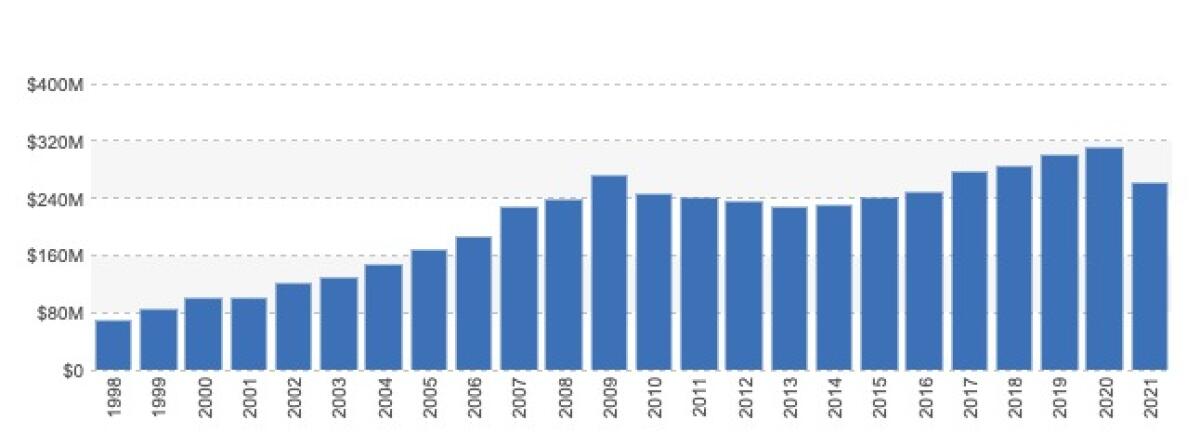

Did I say “clout”? I meant “money.” Big Pharma has spent nearly $263 million on lobbying so far this year, according to the nonprofit influence tracker opensecrets.org.

That puts the industry well on the way to matching or even exceeding its peak lobbying total of more than $312 million, reached last year.

“There is only one reason that Americans are not getting the agreement they should: the political power of Big Pharma and its influence with a handful of Democrats who were willing to prioritize drug company profits over the well-being of the American people,” Weissman says.

So we shouldn’t assume that whatever ultimately emerges from this Congress will be effective. We should, however, at least approach the options with eyes wide open.

Before examining the proposals being considered by Congress, let’s place U.S. drug prices in perspective.

Average U.S. prescription drug prices exceed those in 32 other member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, by more than 2.5 times, according to a report this year by the Rand Corp. The major drivers were brand-name drugs, for which average prices were 3.44 times those in the comparison countries.

At least 10 states are pondering a radical approach to putting a leash on soaring drug prices: force drug companies to explain how they arrived at the price of their costliest new drugs.

Interestingly, average prices for unbranded generic drugs were slightly lower in the U.S. than in the other countries. Generics account for 84% of drugs sold in the U.S. but only 12% of U.S. prescription spending, the Rand researchers found. That’s an indication of how generics prices are overwhelmed by those of brand-name drugs.

“Brand-name drugs are the primary driver of the higher prescription drug prices in the United States,” according to Andrew Mulcahy, lead author of the Rand paper. “It’s just for the brand-name drugs that we pay through the nose.”

The U.S. wasn’t always an outlier on drug prices or drug spending. America kept pace with other developed countries in per capita drug spending until the late 1990s, when the U.S. expanded prescription coverage through Medicare and Medicaid.

The gap widened sharply starting about 2014, according to the Commonwealth Fund. The trend was due partially to increases in healthcare coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but mostly because of the advent of expensive drugs without major competition — or price controls — for treatment of conditions such as hepatitis C.

“Allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices” sounds good, superficially, but the phrase doesn’t do justice to the complexity of the process or the reality of U.S. healthcare.

To begin with, Medicare already has authority to negotiate drug prices, indirectly. That’s through Part D, its prescription drug program, which vests individual health plans with the ability to negotiate prices with drugmakers.

The health plans have the ability to walk away, but only within limits. They’re required to provide at least two drugs in each of several drug classes, and “all or substantially all” drugs in six protected classes: immunosuppressant, anti-cancer, anti-retroviral, antidepressant, antipsychotic and anticonvulsant drugs.

What Medicare can’t do is “interfere” in Part D negotiations between health plans and drug companies. That’s the rule that tends to be targeted by efforts to reform drug pricing. It would be repealed, for example, by the key legislative proposal in recent years is House Resolution 3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now bill.

Trump’s drug price strategy was all talk and no action.

HR 3 was passed by the Democratic-controlled House in December 2019 but stifled by the Republican-controlled Senate. It was reintroduced in April.

The measure would give Medicare authority to negotiate directly with drugmakers, but still only within limits. Starting in 2023, it would have applied to at least 25 brand-name drugs lacking generic competitors, selected from among the 125 drugs with the highest Part D spending (expanded to 50 drugs in 2024). That would include all insulin products, a category that has experienced especially sharp price hikes in recent years. The Senate Democrats’ proposal cuts the total down to 30 drugs.

HR 3, however, outsources some of the negotiation benchmarks to other countries. Although the measure would allow the Secretary of Health and Human Services to base the “maximum fair price” to be paid for any given drug on such factors as research and development costs, production and distribution costs, and effectiveness compared to existing treatments.

As the Kaiser Family Foundation explains, the legislation would define the target price for a drug as the lowest average price in one of six countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom). That might allow the drug industry to game the system by pushing up prices in those countries.

In any event, those countries do the heavy lifting of determining the comparative effectiveness of new drugs being hawked by the industry, a task that the U.S. should shoulder itself.

HR 3 does have a provision that might keep the drug companies at the negotiation table. This is an excise tax imposed on manufacturers that fail to reach agreement with the government, starting at 65% of the previous year’s gross sales of the drug at issue, rising to a maximum of 95% over the following nine months. The tax wouldn’t be deductible against the drugmaker’s other federal taxes.

The excise tax would be a key to gaining any relief on drug prices through negotiation, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Without some form of pressure on drug companies, the CBO has said, the gains would be “negligible.”

If the excise tax stands, however, the CBO estimates that the negotiation provision could save an average of about $45 billion a year in U.S. drug spending. That would be more than 8% of the estimated $535 billion Americans spent on prescription drugs in 2020.

Whether the drug industry will allow any of this to happen is an open question. It has consistently fought price controls and government negotiation, claiming that these steps could reduce their revenue and force cuts in research and development.

Is that so? As we’ve reported, drug industry estimates of the cost of developing new drugs and bringing them to market are almost certainly grossly exaggerated. The truth is that the real obstacle to drug price reform has never been concern over the prospects of drug R&D; it’s politics, and the willingness of the industry to cow legislators through lobbying.

Until Congress shows the spine to face down the industry, reform will be halting and largely ineffective. The talk about Medicare negotiating with drug companies is just a symptom of lawmakers’ unwillingness to take a strong stand. The answer to high drug prices isn’t negotiation, but the exercise of government power. That’s the option that has always been missing in the debate.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.