Column: That big tech exodus out of California turns out to be a bust

Wannabe innovation hubs from coast to coast have been slavering over the prospect that the work-from-home revolution triggered by the COVID pandemic would finally break the stranglehold that California and Silicon Valley have had on high-tech jobs.

Here’s the latest picture on this expectation: Not happening.

That’s the conclusion of some new studies, most recently by Mark Muro and Yang You of the Brookings Institution.

There’s a suggestion that we’re on the brink of an entirely different geography. I don’t think recent history or the nature of the technologies point in that direction.

— Mark Muro, Brookings Institution

They found that although the pandemic brought about some changes in the trend toward the concentration of tech jobs in a handful of metropolitan areas, the largest established hubs as a group “slightly increased their share” of national high-tech employment from 2019 through 2020. (Emphasis theirs.)

Stories of discontented California entrepreneurs decamping for up and coming new hubs or even remote (but broadband-enabled) climes are common fodder in the news.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Times last year published a sort of diary in which Geoffrey Woo, one such expatriate, wrote about his relocation to Miami to flee the crime and pandemic lockdown of San Francisco. He’s still in Miami.

Yet “the big tech superstar cities aren’t going anywhere,” Muro told me. “There’s a suggestion that we’re on the brink of an entirely different geography. I don’t think recent history or the nature of the technologies point in that direction.”

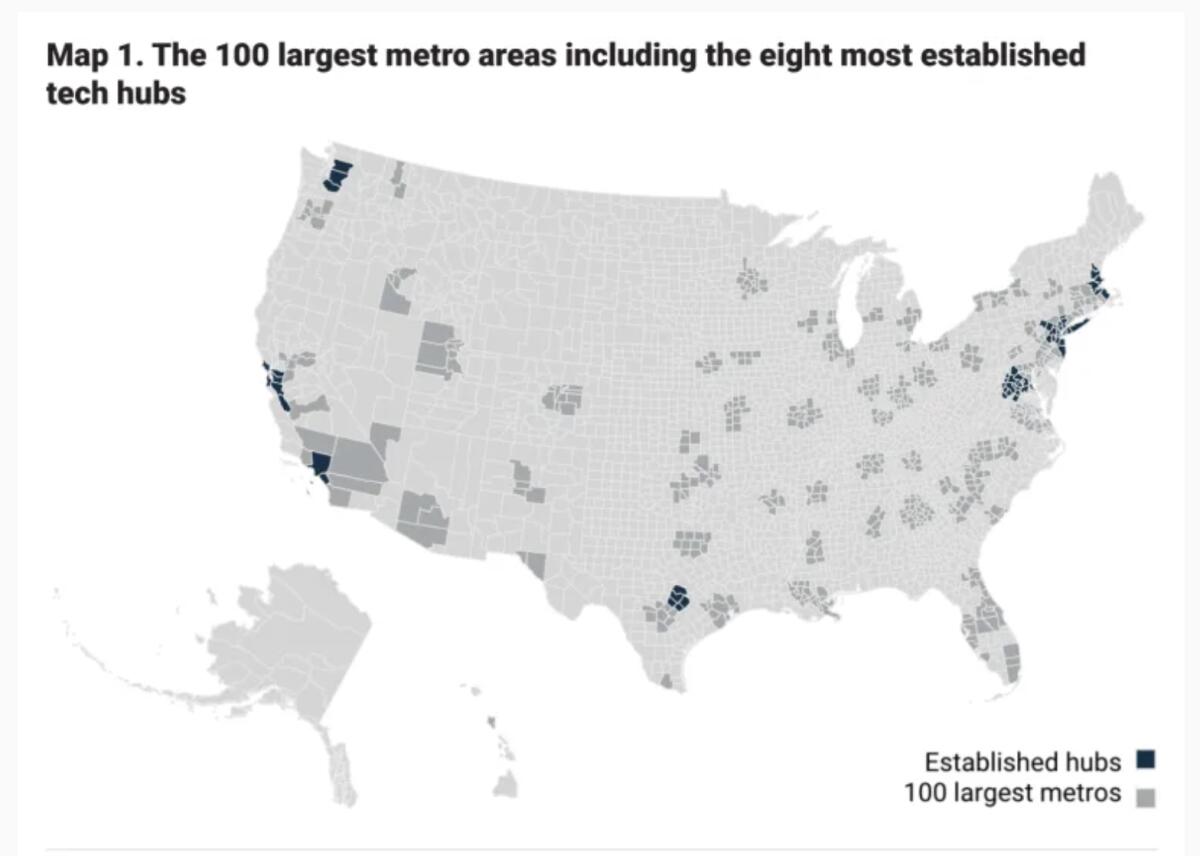

Muro, in harmony with other experts in the geography of work, divides tech employment hubs into three groups.

There are the superstar metro areas: Silicon Valley and San Francisco; New York; Boston; Washington, D.C.; Seattle-Tacoma; Los Angeles; and Austin. Next come “rising stars”: Dallas, Atlanta, Denver, San Diego, Miami, Kansas City, Salt Lake City, St. Louis and Orlando. Finally, everywhere else.

The superstars increased their share of total tech employment by 0.3% during the pandemic — less than the increase of 1.4% they experienced in 2015-2019, but still positive. The rising stars as a group increased their share by 0.1%, down from 0.5% in the earlier period. Both gains came at the expense of other would-be hubs.

California remains a powerhouse, but demographic and economic data do raise some worries.

“The California metropolises really do retain their irreplaceable depth and strength,” Muro says. “That’s not to say there won’t be some movement. Early in the period we saw some exiting, especially from the Bay Area, but it turned out that much of it was within California, rather than to Kansas.”

This shouldn’t be too surprising. The value of concentrated ecosystems in nurturing innovation has been document for decades. As Nicholas Bloom of Stanford and colleagues pointed out in 2020, elite academic institutions attract highly skilled innovators and spin off their learning into new technologies and new industries; their presence tends to attract others like them.

That’s how Boston and San Diego became biotech hubs and Silicon Valley and San Francisco centers of inventive approaches to computer hardware and software. There’s a notable cross-pollination effect: Inventors who move to a city with a large cluster of inventors in the same field experience “a sizable increase in the number and quality of patents produced,” according to UC Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti.

The allure of living and working in such a cluster outweighs the downsides of high living costs, taxes and congestion.

“High-tech clusters tend to be located in cities with high labor and real estate costs — cities like San Francisco, Boston, or Seattle — rather than in cities where costs are low,” Moretti observes, possibly because for creative intellectuals, intellectual productivity outweighs those costs.

Tech companies have been moving some operations away from their traditional headquarter locations or expanding elsewhere, Moretti says, but that was happening long before COVID. “I’m skeptical that COVID-induced changes are driving an acceleration in an exodus of tech firms,” he says.

Muro’s research points to an evolutionary change in high-tech geography triggered by the pandemic, rather than “a wholesale decentralization of tech.” There may be several reasons why a large-scale flight from the big hubs hasn’t happened.

One is that most tech companies don’t plan to abandon office work entirely but expect their workers to commute to work two or three days a week.

This hybrid system “allows employees to move further from their place of work, such as from a city center to a surrounding suburb,” Bloom reckons. “But it does not allow an employee to move to another metro area entirely because they must still commute to work on some days.”

Goldman Sachs, Comcast, AT&T and others are quietly supporting attacks on abortion and voting rights.

Instead, Bloom found increased movement within metro areas, rather than between metros — a trend he terms the “donut effect,” signifying movement out of the central city and into suburbs or exurbs.

Bloom’s data are drawn from U.S. Postal Service change-of-address records and Zillow’s tracking of rent increases.

His findings cast doubt on the theory, put forth by urbanist Richard Florida and economist Adam Ozimek, that habits of remote work would give rise to “Zoom towns,” communities such as Tulsa, Boulder, Colo., and Bozeman, Mont., remote from traditional business centers but inviting for workers who need only keep in touch with their bosses and colleagues digitally via the Zoom and Slack platforms.

While Postal Service statistics do show some movement from densely populated cities to distant locations, the trend is “small relative to the within-metro movement from city centers to their suburbs,” Bloom wrote.

The pandemic-driven shift to remote work does seem to have opened entrepreneurs’ eyes at least to the potential for doing away with centralized workforces.

In a recent survey of tech startup founders, the share of respondents saying they would prefer to start a firm with an entirely remote workforce from Day One rose to 42.1% in 2021 from only 6% in 2020. Among physical locations where the founders said prefer to launch their businesses, however, San Francisco still dominated, at 28.4%, with New York a distant second.

There have been some clues in recent years that the exodus of big business from California hasn’t been all it’s cracked up to be.

In 2020, the headline departures featured in reports of corporate relocations were three: Oracle, Tesla and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. The Brookings study, published this month, mentions three major tech firms: Oracle, Tesla and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. (Brookings cites a fourth — Palantir, a money-losing software company headquartered in Denver, but as of year-end 2021 it employed fewer than 1,900 people in the U.S., some of whom work in California.)

Some of the assertions about a California exodus aim to make political, rather than economic or demographic, points. Consider an August 2021 paper by Lee Ohanian of the Hoover Institution and Joseph Vranich, who happens to be the CEO of a Texas business relocation firm.

Far from being a sober statistical survey of business moves, the paper is more of a screed comprising the usual conservative beefs about California, such as too much regulation. It also makes some surprising assertions: “California is notorious for imposing excessive real estate taxes,” for example.

Actually, California’s property taxes are the 36th-highest in the nation; Texas, Vranich’s home state, ranks seventh, with an effective rate more than twice California’s. Thanks to Proposition 13, California is notorious for, if anything, having low real estate taxes.

Ohanian and Vranich, asserting that corporate headquarters are leaving California in “unprecedented numbers,” offer a database of 265 companies that did so from January 2018 through June 2021. The list includes such non-business businesses as the NFL Raiders, which moved from Oakland to Las Vegas in 2020. The NFL, however, actually approved the relocation in 2017.

The authors don’t give this supposed exodus its proper context, which is how many businesses have been created or moved into California in the same period. The answer, according to the Census Bureau, is 133,503. In the same time span, Texas added 90,916. (By the way, California still hosts three NFL teams, tied with Florida for the most of any state.)

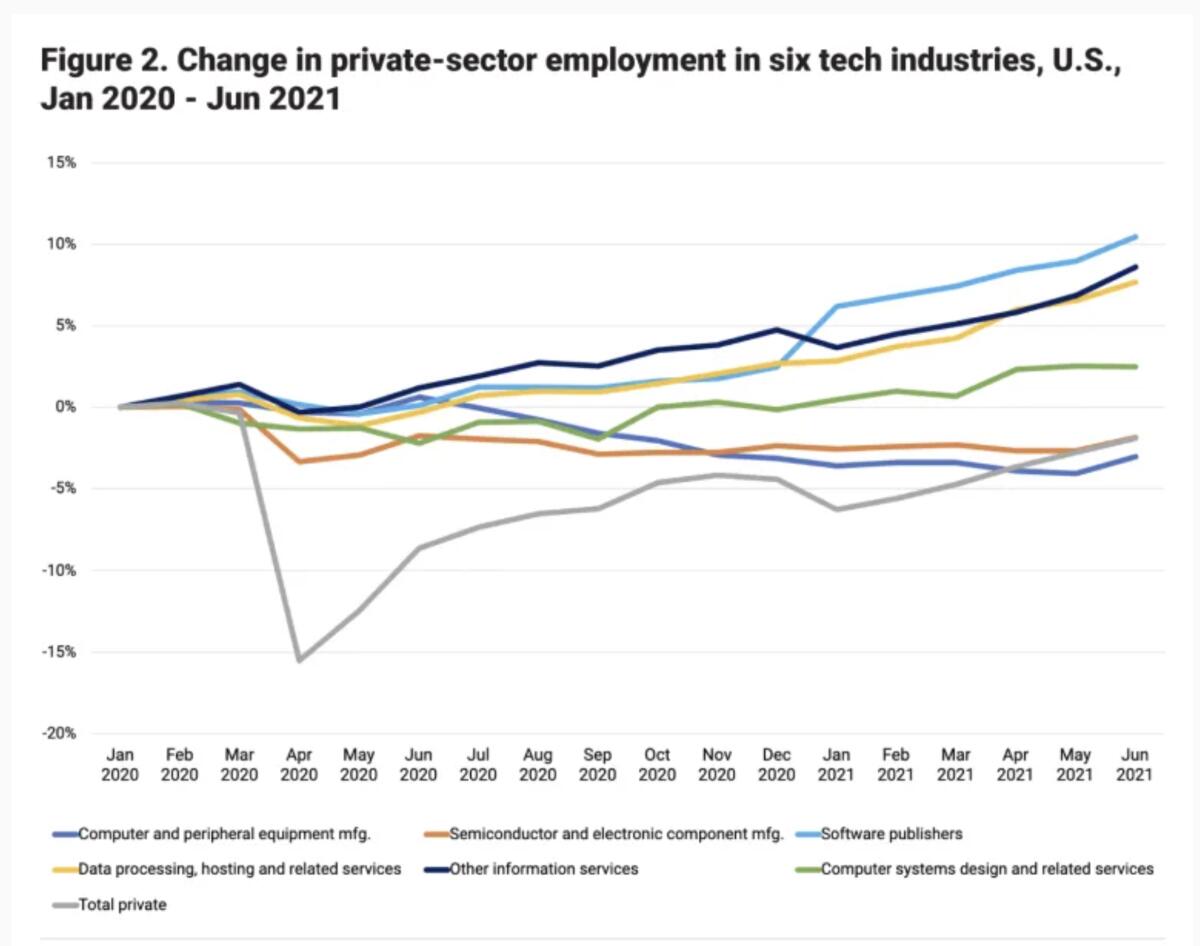

Communities are eager to position themselves as remote tech hubs because of the sector’s economic resilience. Unlike service industries such as leisure and tourism, most tech industries experienced barely a hiccup in their long-term growth trends during the pandemic.

Although employment in semiconductor and computer hardware manufacturing fell from January 2020 through June 2021, Brookings found that software publishing, data processing and information services such as Google and Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook) suffered only brief employment losses early in 2020, but by mid-2021 had larger workforces than before the pandemic.

Would-be tech hubs can’t depend on attracting digital workers naturally, Muro says; they have to work at making themselves seem attractive to a digital workforce. That means building up a technical infrastructure, including broadband access, developing a networking culture resembling Silicon Valley in its early days, and offering good schools and other crucial amenities.

The political environment is also an imponderable factor. Whether aggressively conservative politics in Texas and Florida, including hostility to the LGBTQ community and the contraction of women’s reproductive health rights, will slow the influx of young and well-educated workers is hard to tell at the moment.

But the early signs should worry those states’ leaders. Tech journalist Kara Swisher, who is gay, recently canceled a tech conference scheduled for next year in Miami to protest the state’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law.

The law prompted a workforce uproar at Walt Disney Co., one of Florida’s biggest employers, over the company’s silence about its enactment; California Gov. Gavin Newsom publicly invited Disney to reverse its decision to move 2,000 jobs to Florida from California. (The company hasn’t responded to the overture.)

Disney, Florida’s most powerful corporation, greets the state’s attack on LGBTQ+ kids with silence.

It’s doubtful when, if ever, 100% work-from-home jobs will amount to a large share of employment. Full-scale work-from-home only applies to about 6% of workers, Moretti says. That’s triple the 2% level of the pre-pandemic era, but still an exception to the rule.

For all that, it’s also true that some “rising star” metros may offer entrepreneurs and tech workers some qualities that established hubs have lost. That’s what has kept Woo, who wrote about his decision to relocate, in Miami.

Woo, who runs two businesses in startup mode and a venture investing fund, says he hasn’t found business reasons to regret moving from San Francisco. (The dearth of decent Asian food is the one drawback he mentioned.)

The tech community in San Francisco has become dominated by large established companies led by billionaires, those who have already made their fortunes, Woo told me. The tech community in Miami is more inviting to “people who haven’t made it, who aren’t billionaires.... San Francisco is in harvest mode rather than create mode — it’s harvesting the value of all the dynamism that has been created over the last 20 or 30 years.”

As for Florida politics, “the most impactful policy for normal citizens is COVID policy,” he says. “I’ve been used to not having to wear a mask or show vax cards for every little thing, and it’s been great.”

Conservative social policies, he says, might undergo change as the result of the inflow of a diverse workforce, rather than keeping people away. “As people come in, the policies of the jurisdiction will evolve to match what the constituents want.”

There may be a cultural shift going on in what Moretti calls the “geography of jobs.” But “it’s still unclear how far it will go,” he says. “It will take at least a few years to know.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.