California Politics: A dramatic do-over of maps for Congress

- Share via

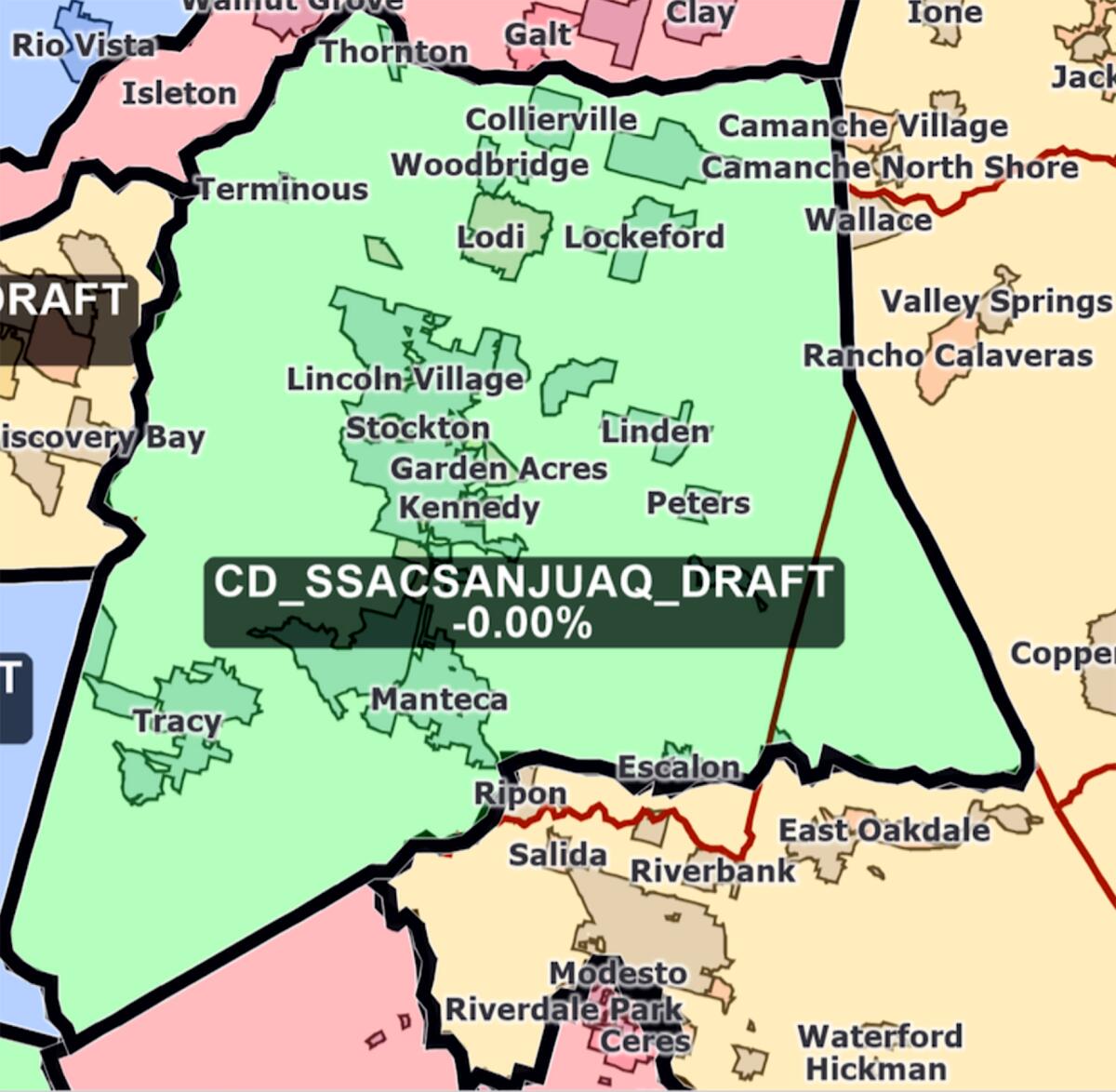

What had been a process of incremental change took a surprising turn on Monday when three members of California’s redistricting commission went all-in starting from scratch on a new congressional district that contained almost all of San Joaquin County, erasing lines that had been drawn just a few days earlier.

It was the last day scheduled by the panel for finishing a map for all of the state’s 52 congressional districts, and big decisions still needed to be made in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

Not only was it time-consuming, but the commission’s legal consultant warned of ripple effects through districts across most of the Sierra Nevada and as far south as Inyo County.

“I want to try it,” said an undaunted Commission Chairwoman Trena Turner. “I don’t want to go back.”

What happened from there was nothing short of a political explosion — several commission members acknowledged they were “blowing up” the maps — that rearranged some congressional alignments that had existed for decades while likely leaving one Democratic incumbent out of luck.

But it’s also what the proponents of independent redistricting seemed to have in mind when they convinced California voters to wrest control of the process from the Legislature, promising maps that were drawn through community input instead of political horse-trading.

Keep San Joaquin County whole

Congressional maps that were drawn in 2011 by California’s first citizens redistricting commission and those crafted by legislators and judges in the two decades prior all divvied up San Joaquin County, anchored by the city of Stockton and the northern gateway to the heart of the Central Valley.

But with the county’s population now at the point that it could — if the commission agreed — merit a congressional district all its own, local leaders engaged in a high-profile effort to stop the split. Some of those efforts were criticized for ties to local Republican politics.

“We need representatives who know our county’s priorities,” San Joaquin County Supervisor Chuck Winn told the commission on Oct. 22 when presenting a map that proposed a unified county for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

But all four of the commission’s early sketches divided the county into pieces. For weeks, the focus was on what to do with Tracy, a city on the county’s southwestern border that has grown into a bedroom community for the Bay Area.

Here’s where chance comes into play: California law stipulates that eight of the 14 state redistricting commission members be randomly selected from a list of qualified applicants. And in that process, San Joaquin County scored two members: Turner, a Stockton Democrat, and Neal Fornaciari, a Republican from Tracy.

Fornaciari, a retired Sandia National Laboratories researcher, had made no secret of how he felt about the 2011 commission’s decision to place his hometown in a district with neighboring Stanislaus County.

“They maybe didn’t get that quite right,” he told state auditors during his interview for a seat on the commission. “I don’t think their justification is quite right.”

From San Joaquin to Sacramento

But it was Turner, the executive director of a Central Valley community organizing network, who spoke first. The commissioners take turns serving as the body’s chair and, by coincidence, Turner was selected to oversee the completion of the draft maps.

She made full use of her power over the proceedings, switching Monday to more real-time line drawing and kicking off the day’s session by asking for new congressional lines to be drawn in neighborhoods around Fresno. Then she set her sights on Tracy.

The effort was quickly embraced by Commissioner Alicia Fernández, a Republican from the small Sacramento River community of Clarksburg. It was Fernández who asked for Tracy and another nearby community, Mountain House, to be added to a congressional district with most of San Joaquin County.

“Are you with me?” Fernández asked Turner.

“Yes, I’m with you,” Turner replied.

Fornaciari then joined the conversation, suggesting to transfer the remnants of the district that included Tracy to a catch-all congressional district sprawling across the rural eastern Sierra.

“That might keep San Joaquin more whole,” he said. “But that gets pretty complex.”

The ripple effect

The need for districts of roughly equal population makes redistricting a zero-sum game. Keep one community together and you have to split another one and maybe one after that. The changes can ripple through cities and counties hundreds of miles away.

Northern California’s population is largely clustered in the Bay Area and around Sacramento. Turner and Fernández’s changes required lines to be moved in districts that swirled from Lake Tahoe toward the Oregon border and back down through the Napa and Sonoma wine regions before spilling back into cities east of the San Francisco Bay.

“Where are we going with this?” asked Commissioner Sara Sadhwani, a La Cañada Flintridge Democrat.

The answer was complicated. Turner, with support from Fornaciari, was focused on San Joaquin County. Fernández was trying to erase proposed congressional splits of neighboring Sacramento County. It would mean moving a lot of little pieces one at a time.

“Let’s try to Tetris this today,” Fernández said as quirky-shaped areas were moved around in the maps onscreen. But when population totals didn’t match up as needed, the commission’s technical consultants started to grab tiny census tracts in the capital city to make the numbers work.

“This started with Tracy,” said David Becker, the commission’s voting rights attorney, to some laughter in the room.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Big changes in San Diego

The Northern California regions were not the only big do-overs on Monday. In San Diego County, the panel grappled with how to break the coastal regions away from Imperial County without infringing on the rural area’s protections under the federal Voting Rights Act.

“The geographic pairings are not making sense with the way the community works, lives and plays together,” said Commissioner Patricia Sinay, a Democrat from Encinitas.

By the end of the night, the commission landed on a solution by putting Imperial into a congressional district stretching to Indio and Desert Hot Springs, a two-hour drive to the north. Commissioners also rethought earlier plans for a big congressional split of Long Beach as well as nips and tucks across the California map on Monday.

But late into Monday night, the effects of the San Joaquin shakeup still hadn’t been settled.

California politics lightning round

Two other commissioners from Northern California — Jane Andersen, a Berkeley Republican, and Pedro Toledo, a “no party preference” voter from Petaluma — rolled up their sleeves and joined the trio from the Sacramento/San Joaquin Valley in smoothing out the wrinkles.

The solution involved changes to more than a half-dozen districts. Fornaciari’s suggestion to move Modesto into the large eastern Sierra congressional district was adopted — now home to portions of 10 counties with what looks like two pincher-like arms on a map: one near Modesto, the other on the outskirts of Madera.

A large congressional district was drawn from Clearlake down to the vineyards of Napa and Sonoma and then east to the college town of Davis. And Sacramento County, formerly proposed for four congressional districts, is now mostly contained in just two.

Hard times for Harder?

The commission’s draft maps, not fully laid out until just before a unanimous vote on Wednesday, kept California’s political chattering class on the edge of its seats.

Four incumbent Democratic members of Congress were affected by the San Joaquin County revisions. Things improved for two of them: Reps. Ami Bera of Elk Grove and Jerry McNerney of Stockton. An analysis by the nonpartisan California Target Book, a company that tracks political campaigns, finds Democratic voters in the majority in both draft districts.

Should the maps remain as they are — and that’s not a certainty — the road ahead might be tough for Rep. John Garamendi (D-Walnut Grove), who would have to run against a fellow Democrat or vie for a new congressional district drawn around cities in the eastern Bay Area.

The guy with no good choices at this point is Democratic Rep. Josh Harder of Turlock. The effort to consolidate San Joaquin County and subsequent deconstruction of a congressional district in Stanislaus County would seem to leave him to either challenge fellow Democratic Rep. Jim Costa of Fresno or Republican Rep. David Valadao of Hanford.

Several other incumbents also face tough choices should the draft maps remain largely intact over the next six weeks. And Harder isn’t the only Democrat who looks to have been drawn out of a seat. Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-Downey) saw the communities she’s represented for almost 30 years redistributed to other districts.

And all of that is in addition to the 120 legislative districts drawn by the state commission, maps that reflect the continued dominance of Democrats in Sacramento and the gradual shift of population, legislative seats and political power from the north to the south.

A request to speak to Turner, Fernández or Fornaciari for this article wasn’t responded to on Thursday. The redistricting commission is now accepting public comments on all of the draft maps and is tasked with finalizing boundary lines before the end of December.

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.