A reckoning in Palm Springs decades after a ‘city-engineered holocaust’

- Share via

Good morning, and welcome to the Essential California newsletter. It’s Monday, April 24.

After decades in the shadows of history, the city of Palm Springs’ role in the organized dismantling of the multiethnic, low-income community known as Section 14 has received considerable desert sunlight in recent years.

Now, the families who lived on the land and their descendants are moving forward in their quest for racial justice.

The Palm Springs City Council is set to vote this week on a plan to hire a reparations consulting group to research the history of the Section 14 evictions, vet claims from affected families and develop a plan for compensation. That follows a reparations claim filed late last year seeking more than $2 billion from the city.

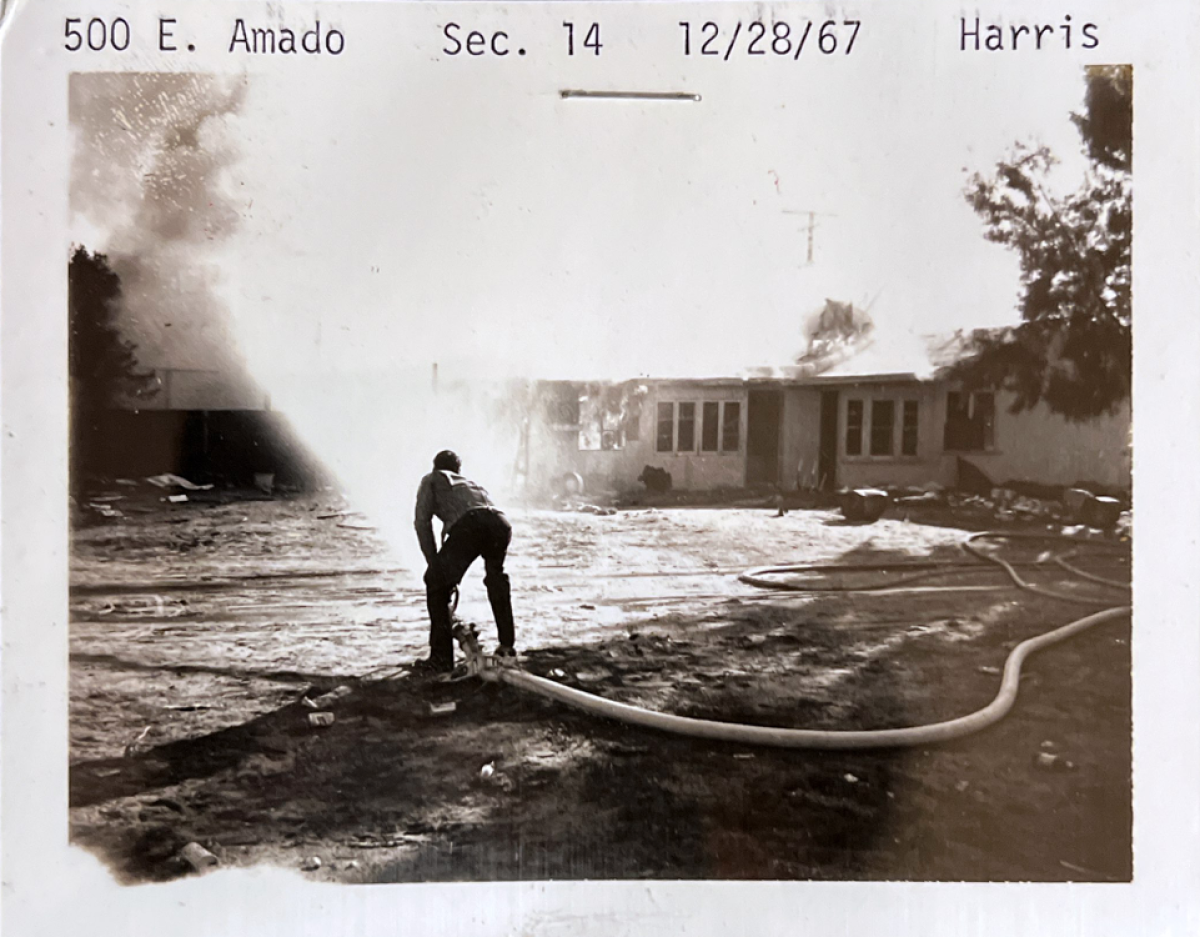

My colleague Gale Holland, who covers homelessness and addiction for The Times, spoke with some of those involved in the claim and recently reported on the history of the Section 14 clearing, in which the homes of Latino, Black and other families were bulldozed or burned in what a 1968 state investigation called a “city-engineered holocaust.”

Gale writes:

The razing of a multiethnic community may strike some as a relic of a time when Black, Latino and Asian people throughout California and the nation faced systematic housing discrimination. But the displaced Palm Springs families say the racism that drove the burnouts lingers...

The reason so many nonwhite families lived in the square-mile parcel known as Section 14 is squarely rooted in racism: it was one of the few places nonwhite residents were allowed to live as segregation thrived in the desert community.

The land belonged to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, but held in trust by the federal government. The arrangement barred tribal members from leasing parcels for more than five years.

That provided an opportunity for thousands of Latino, Black, Indigenous, Filipino and white working-class families to rent small plots. The community grew, as families put up shacks, concrete-block houses, churches, a cafe and more.

In the late ‘50s, the federal government loosened the lease restrictions, and soon big developers came calling. But it wasn’t tribal members who answered. That’s because Congress deemed the tribal landowners incompetent to manage their own business dealings. Instead, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Superior Court in Indio “dipped into the good ol’ boy network to name conservators and guardians, ostensibly to prevent tribal members from being fleeced,” Gale explained.

Among those appointees: the chief of police, real estate agents, a moonlighting judge and the mayor of Palm Springs; hardly neutral parties in the development of the desert community.

Through the 1950s and ‘60s, officials enacted “slum clearance,” Gale writes, and “ran Black families ... as well as Latinos out of prime downtown land, without proper notice or relocation aid, and burned down their homes to clear a path for hotels and shops.”

One descendant of Section 14 residents told Gale that land conservators “colluded” with the city by sending people to knock on doors during weekdays when many residents would be at work or school. If no one answered, bulldozers and firefighters arrived to knock down and burn down homes.

“It got to the point when you saw smoke, you were pretty well freaked out because you didn’t know if it was your house or one of your neighbors’ houses,” former Section 14 resident Joe Abner told Gale. “They were tearing houses down right in front of your face.”

Many families driven out by the burnouts struggled to find housing in Palm Springs, which continued racist deed and lending practices, and moved elsewhere.

Some residents and supporters of city officials of that era push back on the narrative from the affected families, arguing that substandard conditions on the land made evictions necessary.

Areva Martin, an attorney for the plaintiffs in the reparations claim, argued that conditions were bad because the city refused to provide services for the people living there.

The claimants, known as the Palm Springs Section 14 Survivors, say the exodus of as many as 2,000 families out of Palm Springs robbed residents of political power and generational wealth.

The city formally apologized in 2021, with then-Mayor Christy Holstege saying:

“[Those actions] were wrong then, they are wrong now, they created devastation in our community and different outcomes for the Black community and Latino community that still exist today, and segregation that still exists today.”

Should the city reach a settlement, Martin said the money could go toward cash payments, college funds, infrastructure improvements, a Section 14 memorial park and a Section 14 Day, among other things.

“As for the former Section 14 residents, reparations might make amends — officially,” Gale writes, “but they can’t erase the trauma.”

Read Gale’s story here.

And now, here’s what’s happening across California:

Note: Some of the sites we link to may limit the number of stories you can access without subscribing.

L.A. STORIES

The 1993 film “Blood In Blood Out,” which turned 30 this month, didn’t garner critical praise or box office success. But as film critic Carlos Aguilar writes, the film “was saved from obscurity by fervent Latino audiences, who reclaimed it as a cornerstone of their representation in cinema.” Los Angeles Times

Far-fight protesters were removed from a Sherman Oaks library Saturday after disrupting a drag queen reading. The screaming protesters initially refused to leave and police were called to the library, but no arrests were made. Los Angeles Times

POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT

Rep. Pete Aguilar, a Yucaipa native and former mayor of Redlands, used his work on the Jan. 6 committee to build a national profile. My colleague Benjamin Oreskes profiled Aguilar, charting his path to becoming Congress’ highest-ranking Latino — and one of its most powerful Democrats. Los Angeles Times

San Diego’s plan to transform northeastern Mission Bay prioritizes climate resilience. But that’s brought fierce backlash from some tennis players, golfers, boating club members and others who argue the changes threaten recreational opportunities for the land. San Diego Union-Tribune

Support our journalism

HEALTH AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Late April has brought warm weather to much of California, but forecasters say a cooler-than-average May is coming. That could slow the pace of melting Sierra Nevada snow and potentially limit devastating flooding this spring. Los Angeles Times

One solution to flooding could be just outside your back door. There’s movement underway in some L.A. communities to build “green alley” networks, exchanging water-resistant asphalt for permeable pavement and native plants. LAist

CALIFORNIA CULTURE

Liset Garcia’s flowers and produce have made her a TikTok star. The Latina farmer shares her journey into farming, the “therapy” it’s provided her and working through both drought and heavy rain. The Fresno Bee

Disney has suspended fire effects in its “Fantasmic” shows at parks worldwide. That follows an inferno at Disneyland this weekend in which the finale of the long-running show went up in flames — literally — with the big animatronic dragon roasted. The Orange County Register

Free online games

Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games in our new game center at latimes.com/games.

AND FINALLY

Today’s California landmark is from Gary Davis of Westlake Village: the Channel Islands, which “provide remnant exemplars of California’s renowned natural and cultural legacies.”

Gary writes:

This eight-island archipelago is a North American Galapagos; its isolation protects astounding natural diversity and abundance. Consequently, it is the last best place for people to experience pre-industrial California today. Stretching 150 miles along the Southern California coast, the islands are surrounded by deep submarine canyons, productive giant kelp forests on rocky reefs, and sandy beaches. In a mild Mediterranean climate, the mountainous islands catch moisture from fog blown across the confluence of three ocean currents that swirl together in a natural bouillabaisse with thousands of plant and animal species from Mexico to Canada and the far Pacific Ocean.

What are California’s essential landmarks? Fill out this form to send us your photos of a special spot in California — natural or human-made. Tell us why it’s interesting and what makes it a symbol of life in the Golden State. Please be sure to include only photos taken directly by you. Your submission could be featured in a future edition of the newsletter.

Please let us know what we can do to make this newsletter more useful to you. Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.