California drivers kill thousands each year, but murder charges are rare. Here’s why

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Thursday, Nov. 9. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Why fatal crashes rarely result in murder charges for drivers

- SAG-AFTRA and studios have reached a strike-ending deal

- This most underrated California city is filled with small-town charms (and amazing food)

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

When does a fatal crash become murder?

Last month, four Pepperdine University students were walking on a sidewalk along Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu when a speeding driver crashed into them.

Niamh Rolston, Peyton Stewart, Asha Weir and Deslyn Williams were killed in the collision — all four seniors at the university and sisters in the Alpha Phi sorority. The driver was identified as Fraser Michael Bohm, who authorities said was driving his BMW at 104 mph along a curved stretch of the highway just before he collided with parked cars and then struck the four women.

What happened next was a rarity in California: Bohm was charged with four counts of murder. During a news conference, Dist. Atty. George Gascón said the charges against the driver stemmed from his “complete disregard for the life of others.”

I’ve been reporting on traffic violence in Southern California for several years and know from previous data requests that most drivers don’t face felony charges for killing someone with their car — let alone a murder charge.

I spoke with two former prosecutors, a former traffic detective and a street safety advocate to understand why this charge is so rare and what that says about how we view driving in a county where more than 800 people are now routinely killed in traffic collisions each year — and 4,000 people are killed statewide.

They all pointed to an inequitable justice system in which drivers face vastly different criminal punishments for killing someone with their car.

The car is a unique instrument of death

First off, killing someone with a vehicle is simply viewed differently under the law. That difference is codified in California’s criminal law, where manslaughter — “the unlawful killing of a human being without malice” — is divided into three kinds: Voluntary, involuntary and vehicular.

The key difference between murder and manslaughter is intention. There’s also the idea of implied malice, or what’s sometimes called a depraved heart — when someone should have reasonably known that an act was potentially deadly, but they did it anyway.

“You might not intend to kill but you act with a depraved indifference to human life,” explained Neama Rahmani, a former federal prosecutor who’s now president of West Coast Trial Lawyers, where he represents plaintiffs in civil cases.

That’s what Gascón’s office alleges Bohm demonstrated, as my colleagues reported last month:

“Investigators have determined that Bohm was not under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of the crash, but the onboard computer of his car shows he was traveling at 104 mph before he lost control in the deadly collision… It was that data, along with statements by Bohm that he was familiar with the stretch of PCH and that he was aware of the posted 45-mph speed limit, that led to the charges against him, sources say.”

Bohm’s attorney disputed that his client was driving that fast and claimed that Bohm was fleeing another driver in a road-rage incident.

Rahmani and Samuel Dordulian, a former L.A. County deputy district attorney, both said they were surprised at the charges filed against Bohm. They characterized it as a rare and more aggressive prosecution than usual for a reckless driving case. I sought specific numbers from D.A.’s office, but was told their data doesn’t differentiate between traffic deaths filed as murders vs. vehicular manslaughter.

It’s not that these cases never happen, though. A nurse is facing multiple murder charges for a high-speed crash that killed five people last summer. In May, a Riverside County jury convicted a driver of murder for a 2018 fatal crash in which he plowed into cyclists in Palm Springs.

Both attorneys said gathering enough evidence is a challenge, especially since prosecutors are “very risk averse,” Rahmani said – they’re under pressure to win the cases they take on.

County prosecutors evaluate each incident “on a case-by-case basis,” according to Tiffiny Blacknell, a spokesperson for Gascón’s office.

“We look at a variety of factors like speed (and speed limit), driving pattern, location of incident (residential vs. commercial, surface streets vs. freeways, school zones, etc.), was the person [driving under the influence], what is the person’s driving history, did the person have prior warnings, and any other potentially relevant evidence,” she wrote in response to questions I sent. “There is no one determinate factor and the filing DDAs examine the entire case and all the evidence.”

The most violent, dramatic crashes tend to get greater media attention, but people are seriously injured and killed in traffic every day across California. At what speed does common negligence become gross negligence — or demonstrate implied malice?

Dordulian, now a civil law attorney, said determining all that is a subjective process. One prosecutor may feel the available evidence is more compelling than their peer in the next office over.

And prosecutors don’t always agree with the detectives who investigate fatal crashes, gather evidence and recommend charges to D.A. offices.

Moses Castillo, a former LAPD detective, recounted a 2019 crash he investigated while he was with the department’s Central Traffic Division. A big-rig driver struck and killed two sisters, ages 12 and 14, who were legally using a crosswalk on their way to school in South L.A. Castillo determined the driver had been searching YouTube on his phone moments before he turned right and struck the two girls.

“I advocated that they charge this individual with felony vehicular manslaughter and I couldn’t get them to do that,” he said. “And that bothers me to this day.”

The driver later pleaded no contest to two misdemeanor counts of vehicular manslaughter, according to Ivor Pine, a spokesperson for the L.A. City Attorney’s office. He received 12 months of summary probation on each count and was ordered to serve 90 days in county jail, 45 days for each count.

For Castillo, outcomes like that demonstrate an “inequity in justice” for many people injured or killed by reckless drivers.

“Every time we get behind the wheel, we’re getting behind a deadly weapon,” he said. “When we forget that … and we don’t care about our behavior, that’s where it gets very dangerous.”

Does driver bias play into our perceptions of justice?

Damian Kevitt, executive director of the advocacy nonprofit Streets Are For Everyone, often meets with families who have lost a loved one to traffic violence. He told me the focus on a driver’s intent in a fatal crash creates a level of protection that doesn’t exist outside their cars.

“Instead of assuming that you have a responsibility and you have an obligation to drive safely, it’s more… ‘we’re going to assume that you have the best of intentions,’” he said. “That’s not right — not when you’re [operating] a two-ton vehicle that has just as much ability to kill someone as a gun.”

Rahmani, Kevitt, Castillo and Dordulian all pointed to two other key factors they say affect the level of accountability drivers face for traffic killings: media attention and political pressure.

‘Whenever I have a case and it’s not getting the attention it needs from the D.A.’s office, I will do everything I can...call every reporter that I’ve ever talked to... [to see if] anyone’s interested in the story, because that’s the thing that elected officials pay attention to,” Rahmani told me. “The more high profile a case is, the more likely that it’s going to be taken seriously and prosecuted.”

I asked the D.A.’s office about that criticism in this case.

“The actions of the defendant the night he killed four young women support the filing of murder charges,” Blacknell said. “Our expertly trained prosecutors reviewed all evidence and filed charges that are supported by law. Individuals who take their driving privileges for granted and put the lives of the public at risk will continue to be held accountable.”

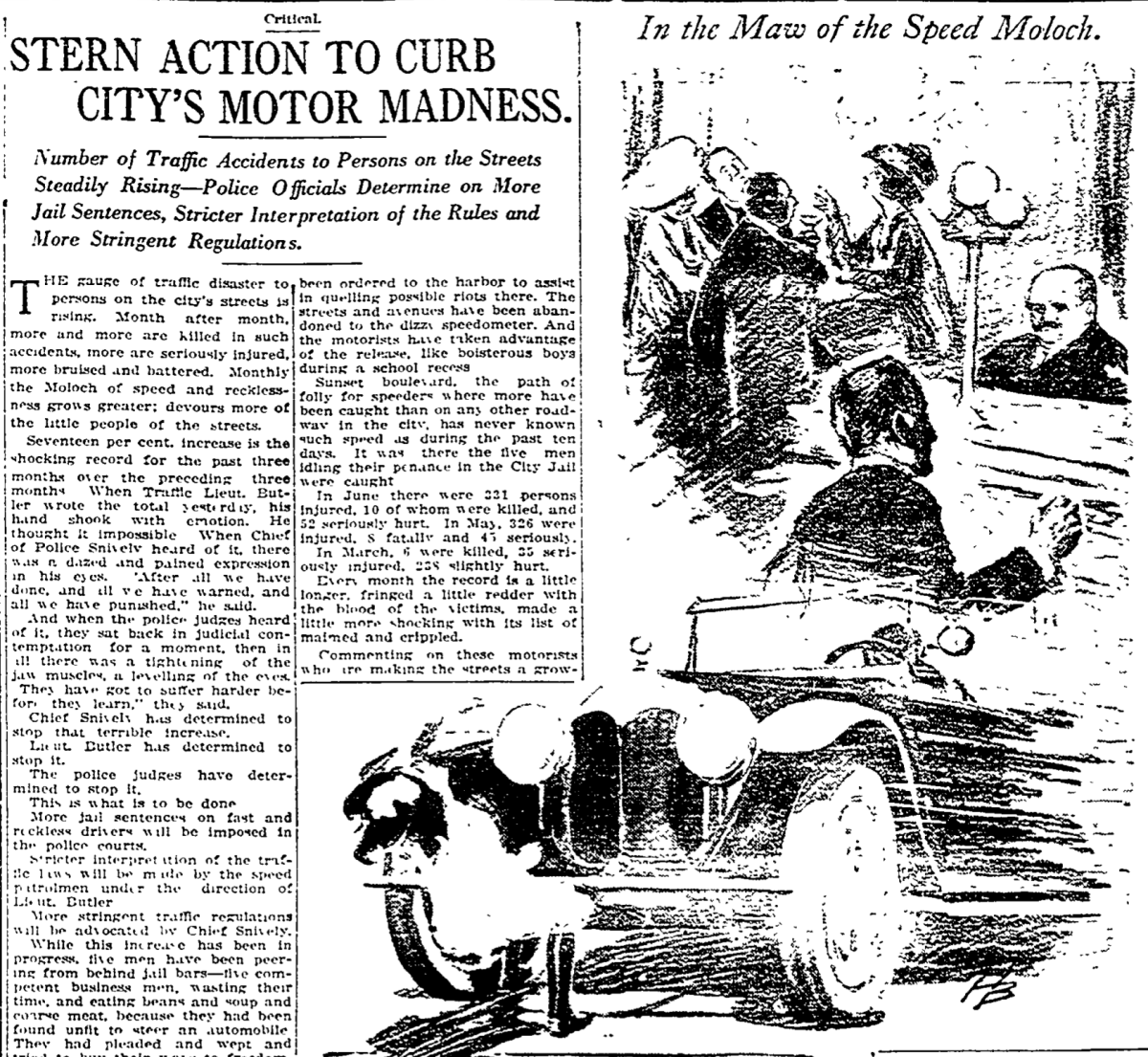

The question of how accountability should look for drivers is a conversation Americans have been having for a century. As automobiles became more widely used in the 1910s and 1920s, drivers were killing thousands of people each year, many of them children.

There was public outcry that has been largely obscured over time as the automobile became the American cultural juggernaut it is today. In a 1921 Los Angeles Times editorial about the lack of justice levied on “speed devils” who crash and kill, the writer focused some blame on the public for its appetite for spectacle in criminal cases while showing “little interest in the ordinary course of justice.”

Dordulian said the fact that driving has become so central to daily life points to a societal bias, which permeates how we think about accountability.

“As a prosecutor, we have to believe that the 12 people that are going to be seated as jurors are going to be able to follow our logic and argument and return a verdict of guilty — but those 12 people sitting there are also all drivers,” he said. “To say that someone behind the wheel [who] really didn’t intend to kill anybody can be a murderer is something that’s hard for us to grasp.”

Today’s top stories

Labor

- SAG-AFTRA’s negotiating committee has approved a tentative deal with the major studios that would end a nearly four month-long strike that has sidelined thousands of workers.

- Actors react to SAG-AFTRA strike ending: ‘We worked hard ... didn’t cave ... got the deal we needed.’

- Column: The Hollywood strikes are finally over. But we won’t repair the damage anytime soon.

Health

- California imports doctors from Mexico to fill gaping holes in farmworker healthcare.

- The Bay Area has reinstated COVID mask orders in healthcare settings. Will L.A. follow?

Climate and environment

- First, dry Santa Ana winds and a fire weather watch. Then get ready for rain.

- With hot October temperatures, this is ‘virtually certain’ to be the warmest year on record.

- Plans to build a $200-million water pipeline across the Mojave Desert to supply the city of Ridgecrest are angering environmentalists, farmers and miners.

Courts and crime

- The man accused of attacking Paul Pelosi and stirring up right-wing conspiracies faces a San Francisco jury.

- A father and son shot, dismembered and burned. This is the dark side of California cannabis.

- An LAPD officer who alleged harassment by former Mayor Eric Garcetti’s advisor gets $1.8 million.

- L.A. County to pay $700,000 to a radio reporter who was arrested while covering a 2020 protest.

- Former Grammys chief Neil Portnow is accused of rape in a new lawsuit.

More big stories

- What does Ohio’s vote on abortion mean to California?

- Everyone but Trump is running out of time — and other takeaways from last night’s GOP debate.

- California banned the sales of flavored tobacco products, but researchers say online sales have boomed.

- Los Angeles County supervisors voted to extend — and slightly increase to 4% — a soon-to-expire cap on rent increases.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Anita Chabria: California prison guards are dying too young. How Norway (yes, Norway) can help.

- George Skelton: Gov. Gavin Newsom needs to focus on his day job.

- Mark Z. Barabak: Overwhelmed? Confused? Here’s what to make of all those presidential polls.

- Opinion: An IED made me a double amputee, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t continue to serve in the Army.

- Robin Abcarian: How the new House Speaker Mike Johnson avoids sin — an ‘accountability app.’

- Editorial: L.A.’s ‘mansion tax’ is a lifeline to ease homelessness, but it remains in limbo.

Today’s great reads

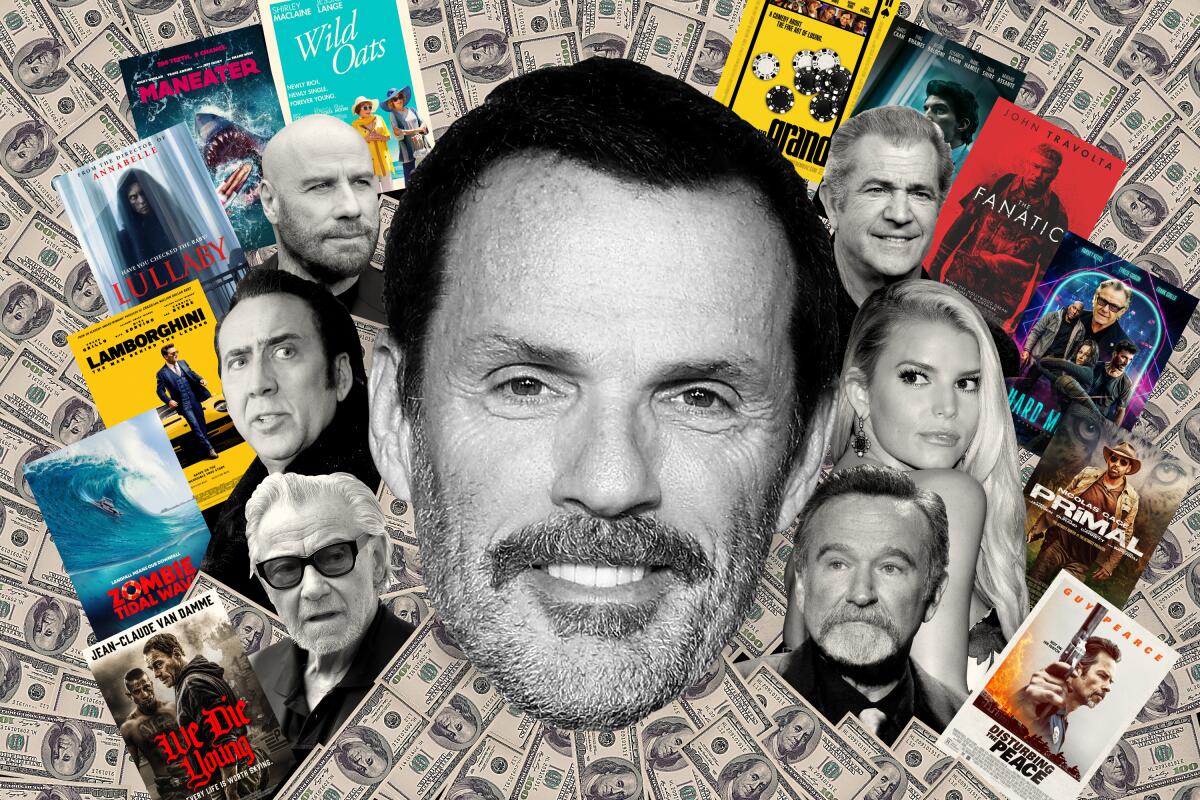

Big-name actors, B-list movies and the indie producer who has faced a trail of fraud lawsuits. Bret Saxon and his companies have been sued multiple times by investors and others who accused him of fraud and misappropriating funds from film projects.

Other great reads

- The Dodgers want Shohei Ohtani. But how far will they go in a potential bidding war?

- In a year of viral country hits sung by angry men, Megan Moroney stakes out a woman’s POV.

- Watch: In a warehouse in the heart of Los Angeles, a dwindling handful of devoted craftspeople maintain more than 80,000 student musical instruments, the largest remaining workshop in America of its kind.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 🥘 California’s most underrated big city is filled with small-town charms (and amazing food).

- 🎊🏳️🌈 They throw some of L.A.’s most-talked-about queer parties. What’s their secret?

- 🖼️ From Blum Gallery to the Huntington, exciting new art exhibits are all over L.A.

Staying in

- 🎮 Chucky, one of Hollywood’s most iconic killer dolls, will bring his murderous tendencies to a gory survival game, “Dead by Daylight.”

- 📺 ‘De La Calle’ docuseries explores the evolution of Latin music and its connection to hip-hop.

- 🍗 Here’s a recipe for chipotle-braised chicken with tomatillo bean salad.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... from our archives

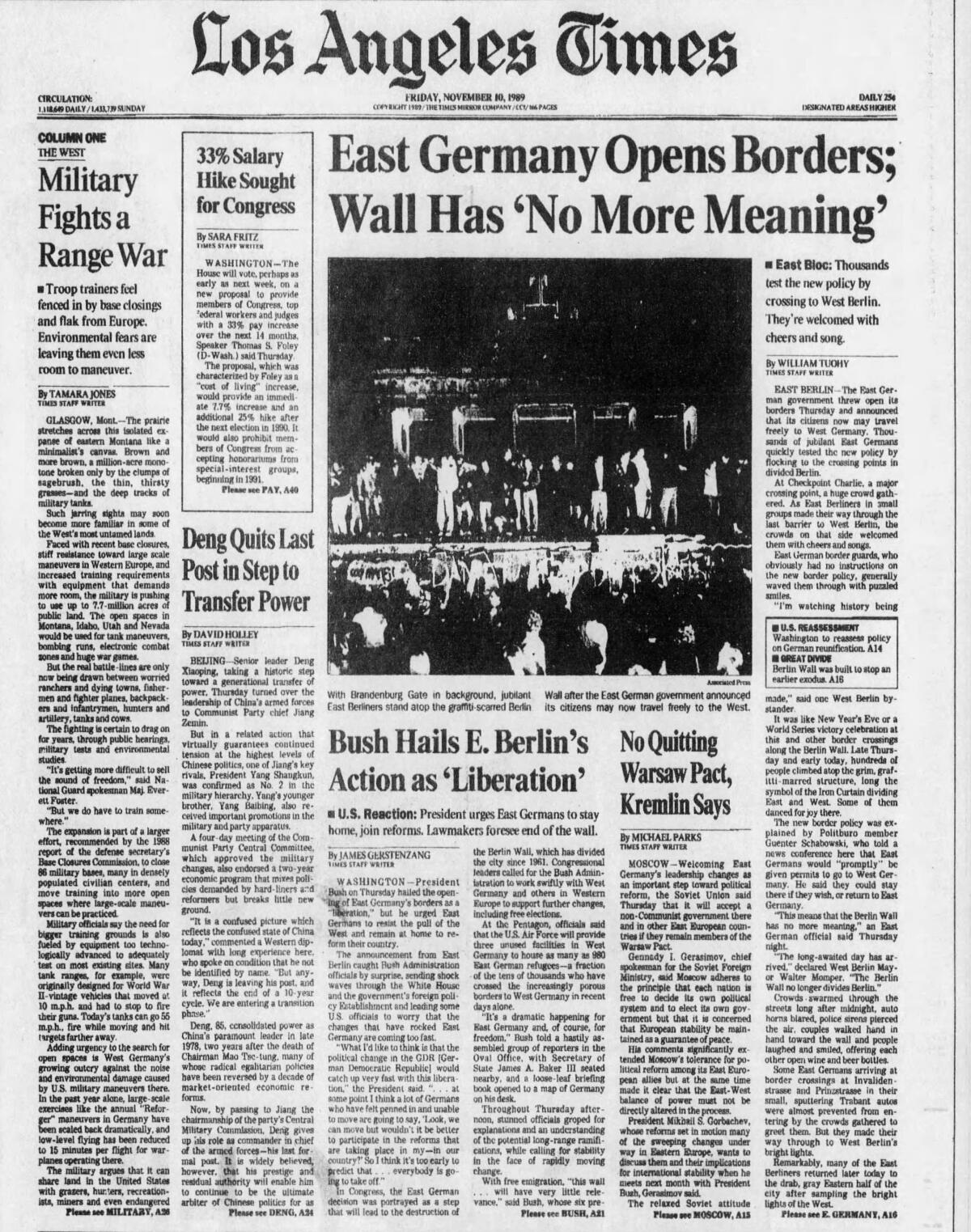

On Nov. 9, 1989, the East German government threw open its borders and announced that its citizens may travel freely to West Germany. Times reporter William Tuohy was on the scene, reporting that it was like New Year’s Eve or a World Series victory celebration as hundreds of people climbed atop the grim, grafitti-marred structure, long the symbol of the Iron Curtain dividing East and West.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Laura Blasey, assistant editor

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.