Why Berkeley can’t stop fighting over People’s Park

Good morning. It’s Tuesday, Jan. 9. I’m Times reporter James Rainey. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Why Berkeley can’t stop fighting over People’s Park

- Why do airplanes have door plugs?

- 5 epic outdoor adventures that will make you feel powerful in 2024

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Why Berkeley can’t stop fighting over People’s Park

Tourists visiting Berkeley might be forgiven if they are underwhelmed by storied, much-fought-over People’s Park. The 2.8-acre green space south of the UC campus might be most notable for what it has lacked for many years: a coherent recreation program, regular maintenance or trash pickup, and discernible rules.

Fervent believers in the park said they loved it, in part, for its very nonconformity, and more. That laissez-faire environment meant the park could be whatever people wanted it to be, from free-form concert venue to camping spot for the homeless to gathering place for political organizing. (Detractors said it was unsightly and unsafe.)

People’s Park — remade by a university takeover last week and a plan for a massive housing complex — survived because generations of Berkeley’s city and campus leaders treated it as an untouchable symbol of the community’s radical past and its dedication to a progressive future. The university’s successful effort to wall off property it has owned since the 1960s appears to have given UC the greatest control it has had over the space since the start of the long-running controversy.

It began in 1969 when the university tried to build a fence around the space. A group of students and local activists tore it down and rejuvenated the garden they had planted there a month earlier.

The university and a small army of police surrounded the park last week, clearing the way for a wall of metal cargo containers that entirely encircled the park by Sunday.

The fight over the park has remained fervent after 54-plus years because support of the park has been reinvigorated over the decades by linking it to a host of other progressive causes.

Demonstrators on nearby Telegraph Avenue talked about the loss of a space for homeless people (though the university has paid for motel rooms for anyone who once stayed there and site designs include permanent supportive housing for 125 homeless people) and the “corporate” takeover by town and gown officials allegedly in the pocket of nefarious developers.

Some of the protesters also said their struggle for People’s Park had much in common with the fight of Palestinian people to have a safe and secure homeland in the Mideast.

“It’s the same situation [here] with the vulnerable people and the assaults on them,” said one woman protesting Sunday. “It’s not as bad here, certainly. But they stand up for their right to exist. And [other] people want to exploit people in any way that they can.”

Another protester decried the university’s bid to build on the park, which still requires clearance from the state Supreme Court. She blamed the Berkeley City Council, which has generally supported construction in the park. She then quickly jumped to condemn the council for not passing a resolution calling for a cease-fire in Gaza.

In earlier generations, pro-park protesters tied their work to the freedom fight in South Africa. They fought university moves to secure the park, while also demanding UC pull its investments in the African nation during its apartheid era.

And a perennial cause of park supporters has been police reform. Protests about the park over the last five decades also reliably objected to the police, including the fact that the university maintains its own police force.

The future of People’s Park is endangered today like no time since its creation in April 1969. But those who hope to open the park to the public again (without the high-rise dorm complex) can be expected to find no lack of inspiration, both in Berkeley and the world beyond.

Today’s top stories

Alaska Airlines blowout

- Why do planes have door plugs? And other questions about the Alaska Airlines blowout, answered.

- United Airlines finds loose bolts and other problems on door plugs of Boeing 737 Max 9 jets.

- Alaska Airlines flight: Cockpit audio is lost, and a mysterious warning light is investigated.

Elections 2024

- Voters in California’s Central Valley will go to the polls twice in two weeks this spring to select a new representative in Congress.

- Is Trump immune from the law? His case will separate a president’s ‘official acts’ from crimes.

Climate and environment

- Freezing temperatures are coming to parts of Southern California this week.

- Researchers discover thousands of nanoplastic bits in bottles of drinking water.

- Earth reaches grim milestone: 2023 was the warmest year on record.

More big stories

- Who was the decapitated woman in the California vineyard? Authorities finally figured it out.

- The nation’s largest single-family home landlord is to pay $3.7 million in a California rent-gouging case.

- California wants to reduce traffic. The Newsom administration thinks AI can help.

- Judges put a new California law barring guns in many public places on hold again.

- Chaos on the borders, but rising immigration is driving California’s population and labor force growth.

- With COVID on the rise, your at-home test may be taking longer to show a positive result.

- California poultry farmers are seeing a spike in avian flu, forcing millions of birds to be destroyed.

- Shohei Ohtani could avoid paying tens of millions in California taxes. Not so fast, state says.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- George Skelton: Trump is dangerously unfit for office. But leave him on the ballot so voters can give him the boot.

- Opinion: This Supreme Court case from California could ease housing shortages everywhere.

- Steve Lopez: An L.A. institution closes its doors, and Lawrence Tolliver wonders what’s next.

- Column: Diet culture tricks us into thinking our cultural foods aren’t healthy.

- Opinion: Protecting Alaska’s wilderness — and our Indigenous way of life — is critical to a green future.

- Opinion: Why pushing STEM majors is turning out to be a terrible investment.

Today’s great reads

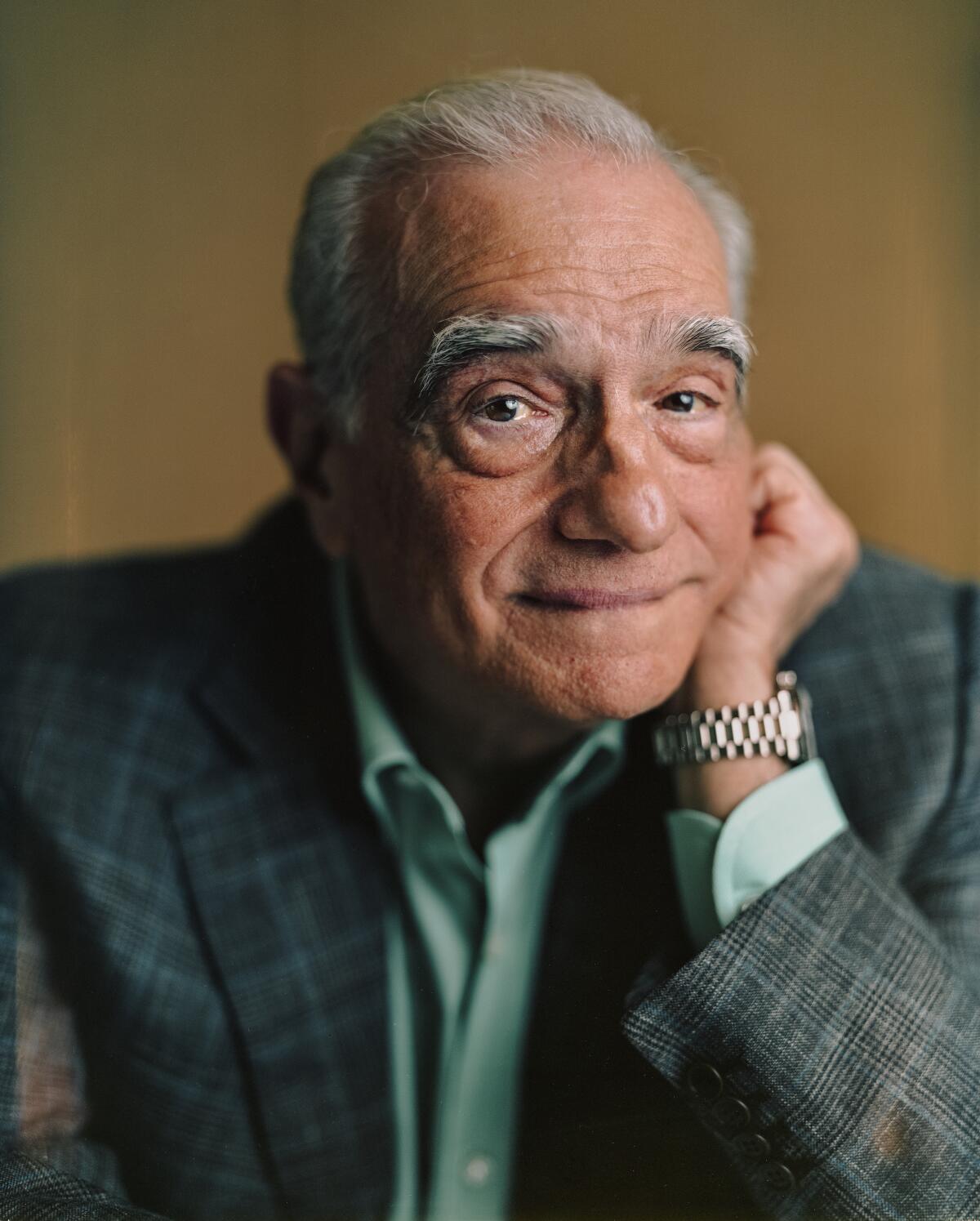

For Martin Scorsese, it’s all about forgiveness. The 81-year-old director talks about his decade in L.A., using film to find his better self and why his next movie will be about the teachings of Jesus.

Other great reads

- Questions about NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission put JPL jobs in jeopardy.

- The L.A. Public Library is getting into book publishing. Why it makes total sense.

- How Danielle Brooks adds fuel to Oprah’s fire as Sofia in “The Color Purple.”

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 🎿 5 epic outdoor adventures that will make you feel powerful in 2024.

- 🍚 23 newcomers to the 101 Best Restaurants in L.A. guide to visit ASAP.

- 👩🏽🍳The next pastry craze should be these flaky, golden nazooks for Armenian Christmas.

Staying in

- 📖 Naomi Osaka is staging her comeback. Here’s what a new biography reveals.

- 🧀 Here’s a recipe for parmesan mac n cheese.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... a great photo

Show us your favorite place in California! Send us photos you have taken of spots in California that are special — natural or human-made — and tell us why they’re important to you.

Today’s great photo is from Times photographer Christina House of Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff, who gave us an inside look at their life in L.A.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

James Rainey, reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Laura Blasey, assistant editor

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.