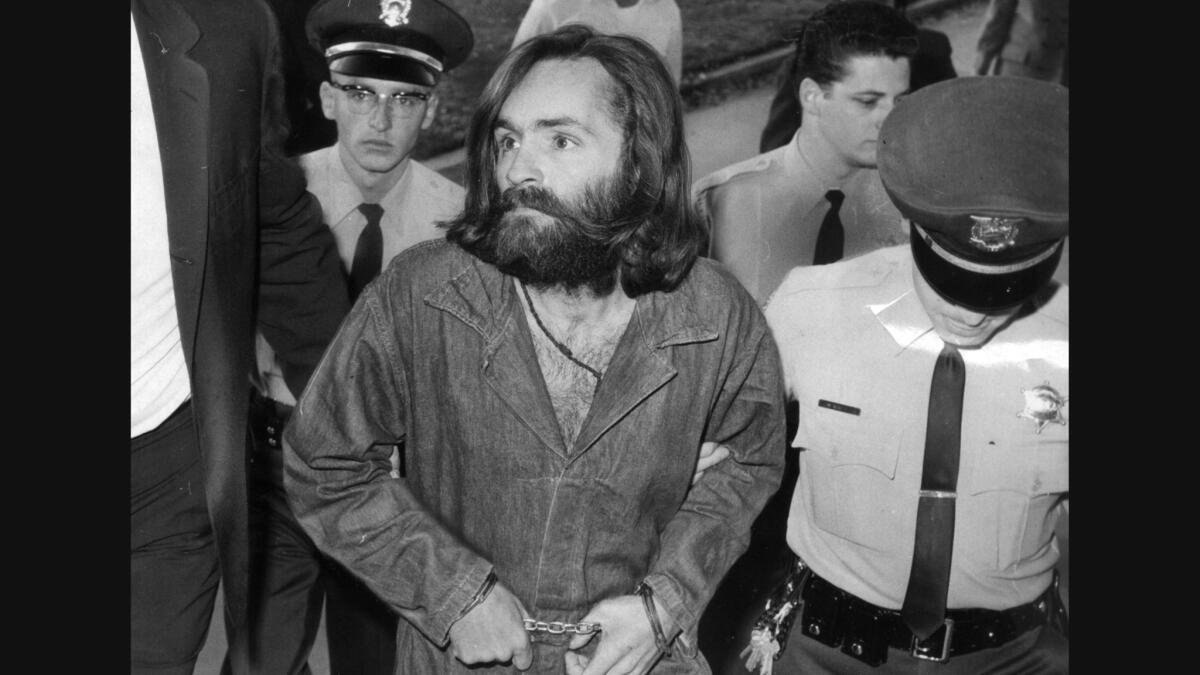

Mass murderer? Cult leader? Musician? Charles Manson’s son wrestles with father’s legacy

Speaking to the media for the first time in 26 years, Michael Brunner, son of late convicted murderer Charles Manson and follower Mary Brunner, discusses his upbringing, his relationship with his mother and how he came to be “at peace.”

- Share via

The soft-spoken man with the crooked smile and bright blue eyes wants to change the way the world thinks about his father.

He says his dad has been misunderstood for half a century. Unfairly blamed. Wrongly vilified. The man is 51. His name is Michael Brunner.

His father was Charles Manson.

“I would say 95% of the public looks at Charlie as this mass-murdering dog, and it’s really, obviously, just not true,” Brunner says. “He didn’t necessarily kill.”

Brunner stops. He is very nervous. He has spoken publicly about his notorious bloodline just once before, and that was 26 years ago. He is out of practice and deeply conflicted. He has guarded his privacy for decades. But now, loyalty to a biological father he has never known wins out.

A reporter wanted new sources on Charles Manson. Then he found Manson’s son.

“Can we start again?” he asks.

He continues. Then pauses. Whispers. “I thought this was going to be so easy.”

Very little is easy when you’re the only son of America’s most famous cult leader and Mary Theresa Brunner, the first member recruited into the Manson “family,” as his followers were known.

When the man who shares your nose and your grin persuaded his disciples to commit nine gruesome murders in what prosecutors argued was an effort to incite a race war on orders imagined to be encoded in the Beatles’ “White Album,” a scenario they referred to as “Helter Skelter.”

When you have decided it is time to set the record straight.

“I guess I’m here now for, just for posterity, [to] let people know where I’m standing now,” Brunner says. “I’m still not looking for any kind of celebrity. I mean, this isn’t something that you run around and brag about.”

On Aug. 8, 1969, Brunner — born Valentine Michael Manson, aka Sunstone Hawk or Pooh Bear — was 14 months old. His mother was behind bars, locked up in L.A. County’s Sybil Brand Institute for Women, having just been arrested for using stolen credit cards.

That was the night Charles Manson dispatched Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian to a house on Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon. Each had a change of clothes. All but Krenwinkel wielded a knife. Watson had a gun.

Early the next morning, actress Sharon Tate was dead, stabbed 16 times and trussed to a beam in her living room. She was 8½ months pregnant and had begged to save her unborn son. Four others — Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski and Steven Parent — died that night at the hands of Manson’s followers. The next night, “family” members slaughtered Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in their Los Feliz home and desecrated their corpses.

In his opening statement to the jury in the nine-month trial, chief prosecutor Vincent T. Bugliosi described Manson as a “dictatorial leader” whose followers were “slavishly obedient to him,” and called Manson’s principal motive “almost as bizarre as the murders themselves.”

That motive, he said at the time, “was to ignite ‘Helter Skelter,’ in other words, start the black-white revolution by making it look like the black people had murdered the five Tate victims and Mr. and Mrs. LaBianca, thereby causing the white community to turn against the black man and ultimately lead to a civil war between blacks and whites, a war Manson foresaw the black man winning.”

By the time Manson and his crew had been convicted and sentenced to death, “Pooh Bear” was living with his maternal grandparents in Eau Claire, Wis. George and Elsie Brunner eventually adopted the boy, gave him their name and raised him as their son.

They “gave me what I needed to survive and thrive, and pushed me through school and pushed me through sports and made sure that I was doing the right thing,” Brunner said in a wide-ranging interview in early July. “I have been loved.”

When his adoption was official in 1976, Brunner’s grandparents threw a party. The neighbors came. Everyone brought gifts. It was like having an “extra birthday,” he said.

“I think they wanted to get rid of the Manson name because of school and to make me a little more normal,” he said. “You know, so I wasn’t being pestered or bullied or that sort of thing, which didn’t happen much.”

But his small-town Wisconsin childhood was fraught with complications. Brunner called his grandparents Mom and Dad. Because of the adoption, Mary was legally his sister; his aunts and uncles were his cousins. Still, he said, he knew that the woman who called every Sunday from a California prison where she was serving time for armed robbery was his mother —which eventually led to questions, he said. If that’s my biological mother, who’s my biological father? George and Elsie never lied to him, Brunner said, but he was never good with names, would forget who his father was, would ask and ask and ask.

“ ‘What’s my father’s name again?’ ‘Charles Manson.’ And then I’d ask them to tell me about him,” Brunner recounted. “ ‘Oh, he’s a crazy guy.’ … I don’t think they lied. They told me what I needed to hear and what they needed to say.”

Then a classmate at Arlington Heights Elementary School passed him a note. Brunner thinks he was in third grade, maybe fifth. The note said his father was a murderer. And he started to realize that Charles Manson was “a bigger deal than just some guy.”

A high school friend who was “kind of a fanatic into anything cultish or, you know, off the wall,” he said, “filled me in on a lot of things. But, again, she was reading the same narrative that everybody else was at the time.”

Charles Manson, evil genius, who persuaded his followers to kill.

“She, of course, thought it was cool, and I thought it was something I didn’t want to deal with,” he said. “So I really wouldn’t pay a whole lot of attention…. [But] it doesn’t matter how deep you bury your head, you’re going to hear about Charles Manson.”

Still, he insists that he had an “average” childhood, that “this whole Manson thing” did not occupy his time, that his life was 99.9% “as normal as anybody else’s.” He was into skating and skiing and water sports, bike riding and hanging out with friends. He was, he said, “like any other kid.”

“And then there’s that one little tenth of a percent,” he said. “And everybody has that, really. I mean, everybody has a little something in their history that, I’m not going to say embarrasses, but they keep in the closet. And that was my little tenth of a percent of a thing that stayed in the closet.”

Brunner is 6 feet tall, height he gets from his mother’s side of the family, not from his famously diminutive father. His curly hair is sandy brown, his beard going rapidly gray.

He describes himself as “kind of an average guy…. [I] spend a lot of time in the woods, in the water.” He enlisted in the Army straight out of high school, was self-employed for several years and now works in manufacturing.

As he talks, he alternates between forthright and skittish, open about the effects of half-a-century-old violence, still concerned about his loved ones’ safety.

He will not talk about his son, who is in his late 20s, or the partner with whom he lives on 56 acres, where they strive to be sustainable, with chickens and ducks and berry plants and a small orchard. He will say only that his home is “somewhere in the rural Midwest.” And he refused to be interviewed anywhere near it.

He said he spoke to KCBS-TV in Los Angeles when he was 25 because the media had been “hounding” his grandparents and he did not want them to be upset. It was 1993, government agents had carried out a siege on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, and there was heightened interest in the children of cults.

At the time, Brunner was circumspect, working hard to put distance between the murders and the normal life he was trying to lead as a parking valet who dreamed of someday owning his own business. He said he was “sorry [about] all of what happened, you know. I wish things could be different. But they’re not.”

And he shied away from the books, articles and movies that sprang from the Manson “family” and its exploits — until the end of 2017, when Charles Manson died of cardiac arrest and respiratory failure triggered by the colon cancer that had metastasized throughout his body. His grandparents had died long before.

That’s when Brunner began reading up on his famous father, came across Nikolas Schreck and reached out to the self-described “singer, musician, author, filmmaker and Tantric Buddhist meditation teacher.”

Schreck, who is based in Berlin, lectures on what he calls “the Charles Manson conspiracy.” He wrote a 991-page book titled “The Manson File: Myth and Reality of an Outlaw Shaman.” He spent hours interviewing the cult leader and directed the 1989 documentary “Charles Manson Superstar.” His work has shaped Brunner’s thinking about Manson. Today, Brunner describes Schreck as “a great friend.”

“I think the public has been fed some untruths, and this whole thing has been glorified and glammified and blown out of proportion,” Brunner said of the slayings and his father’s part in them. “I mean, do we believe in brainwashed zombies out killing people?

“Did [Manson] order these crimes? I don’t believe that he did. I believe that it was something manufactured after the fact. This ‘Helter Skelter’ thing, when you look into it deeply, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

If not “Helter Skelter,” then what? A drug deal gone bad, Brunner and Schreck posit. A major cover-up on behalf of Hollywood elites. Mafia involvement. The Tate-LaBianca murders as copycat killings to cover up the earlier slaying of musician Gary Hinman by “family” member Bobby Beausoleil.

Schreck said in an interview from Berlin that he had helped Brunner “to understand who his father was as a human being. Not necessarily a great person or a good person, but not the monster that has been described by the mass media.”

Manson, he said, was “a criminal for sure, but not this evil incarnate cartoon character that the media and the courts and now the public have believed in as the scapegoat.”

Schreck described Manson as “a talented, poetic musician with wisdom and with a strong, powerful philosophy, who got caught up in these tragic crimes. But he was not the sole instigator and responsible for the crimes.”

Bugliosi died two years before Manson and cannot defend his prosecution. But Stephen Kay, who helped put the Manson “family” behind bars and keep its members there after the death penalty was abolished, vehemently denies any motive other than Manson’s alleged efforts to start a race war.

“It’s not drugs,” Kay said in a recent interview. “It’s no copycat murder for the Hinman murder. It’s ‘Helter Skelter.’ … That was the motive that was proven in court. And that’s the motive that the jurors convicted these defendants on. And that was the real motive.”

Brunner never knew his biological father. He resisted Manson’s efforts to establish a relationship for most of his life, ignoring letters written from prison. But while working as a military contractor in Afghanistan not long before Manson’s death, Brunner said, he reached out for the first time.

Winters in Afghanistan are long and cold, he said, but he had internet access and time to kill. Poking around online, he found people who seemed to respect Manson and claimed to speak with him on a regular basis. He shot off a couple of emails. And he did not hear back.

Several weeks later, he said, a postcard from Manson showed up at his home in the United States. It said, simply: “Write on. Write, write, write on.” Brunner took that as a request for correspondence.

He said he meant to write back.

“Days turned into weeks,” he said, “and weeks turned into months. And I just never did it. And then it was too late.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.