Day-Glo masterpieces are fading. A conservator and her team are racing to save them

- Share via

Deep in a basement laboratory at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, conservator Kamila Korbela peered at the moon-cratered image on the screen of her microscope, searching.

It was a speckle of paint that outwardly appeared no different from a half-dozen others in her portfolio. But the museum’s sophisticated laser microscope told a different story.

For the record:

1:14 p.m. Sept. 11, 2019This article refers incorrectly to a piece of equipment at the Getty Conservation Institute. It is a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer, not a gas chromatic mass spectrometer.

9:08 a.m. Sept. 5, 2019An earlier version of this article said Day-Glo Color Corp. is based in Dayton, Ohio. The company is based in Cleveland.

Instead of magnifying the sample, it measured the vibration of its chemical elements. The readings showed that this fleck of color was unlike the others.

For the crusading conservator, this was a clue to unraveling an urgent mystery that is as much about art as it is physics and chemistry.

Korbela is trying to save “Bampur,” a migrainous color-block behemoth painted in 1965 by the influential modern artist Frank Stella — on view for the first time since 1980 in a LACMA retrospective. Like her paint speckle, it vibrates. At least, it used to.

“The yellow has definitely faded at a faster rate than the pink or the blue,” which are still so unnaturally bright that Korbela could work on them for only a few minutes at a time before getting a headache.

“Yellow is particularly difficult,” she said. “You can’t replicate it unless you replicate the constituent dyes. And it’s all secret.”

This secret is called Saturn Yellow.

It is the trademarked name of a fluorescent chartreuse — think caution tape or a high-voltage sign — that conservators say is among the most photochemically complex paints ever made by the Day-Glo Color Corp. of Cleveland.

Day-Glo still makes Saturn Yellow, although conservators say the modern formula is significantly different from the one used by trailblazing modern artists in the 1950s and ’60s.

Korbela said she hoped to get the company’s help in restoring the work — to secure a copy of the formula, or samples of dry pigment for conservators to test — but after months of trying unsuccessfully to reach them, she gave up.

But it didn’t quash her ambition. Rather, it set in motion a laborious effort to reverse engineer the hue’s midcentury formulation, and her nearly two-year quest has drawn interest from prominent figures in art conservation.

“It’s not just to treat this one painting that happens to belong to LACMA. … I think the outcomes will be a lot more significant,” said Margaret Holben Ellis, chair of the Conservation Institute at the New York University Institute of Fine Arts. “There’s a lot of Day-Glo out there. It’s in every kind of artwork imaginable.”

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times.

The company said its current paints work well for restoration purposes but that it would not divulge proprietary information. Tom DiPietro, Day-Glo’s vice president of research, put it this way: “It’d be like giving you the formula for Coke.”

But after The Times described the LACMA team’s efforts, the company agreed to provide Korbela’s team with pigment samples and a data sheet with some limited details about their composition.

The future of some well-known works of modern art could hang on Korbela’s research, experts said. If the Day-Glo shades can’t be replicated, many fear that renowned works such as “F-111,” James Rosenquist’s 86-foot long protest piece, and Andy Warhol’s “Flowers” could literally disappear.

“These paintings contain a glowing ghost that cannot be captured on a photograph,” said Stefanie De Winter, a Belgium-based conservator who is an expert on fluorescent art. “I think that if we wait for another 50 years, they will be milky-colored ruins, which will have lost their original effect and meaning.”

As novelist and merry prankster Ken Kesey told the Daily Telegraph in 1999: “Nothing looks worse than faded-out DayGlo.”

Nothing.

::

You’ve seen the work of the Day-Glo Color Corp. even if you don’t know you’ve seen it. The company’s shades are a packaging staple, the secret sauce that gives a Tide box its sparkle. Its pigments have long been popular in public art, from murals in Miami to the protest graffiti painted on the Berlin Wall.

What makes the company’s colors so revolutionary is that they radiate in sunlight, while ordinary “neon” pigments glow only with black lights in the dark. This atomic innovation is what drew artists and industrial designers to the medium. Day-Glo paints are intrinsically technical, a truly Space-Age material.

Nothing like this exists in nature — these are man-made colors.

— Margaret Holben Ellis, chair of the Conservation Institute at the NYU Institute of Fine Arts.

“Nothing like this exists in nature — these are man-made colors,” said Ellis, who is president of the American Institute for Conservation, a nonprofit based in Washington. “They look very alien, and that’s one reason Frank Stella liked them.”

More often than not, the colors are used as highlights, but the 9-foot-tall “Bampur” is 100% fluorescent paint. Viewing it for more than a minute is ocular agony, the visual equivalent of an overdose.

“When I started out with ‘Bampur’ [a colleague] was giving me different gray cards to rest my eyes on,” Korbela said. At times, she said, examining the painting at 10-times magnification was unbearable.

The pain of looking at “Bampur” is a function of photo-physics — electron-level exchanges of energy that convert invisible energy to visible light, creating colors so vibrant they scream.

“It’s literally electrons jumping from high to low energy levels,” Korbela said. That’s how all colors work — it’s just that the electrons in fluorescent pigments have more skips in their step.

This subatomic dance is what gives fluorescents their astral glow. They shimmer on the horizon of visible light, close to the limit of the human eye and far beyond where most cameras can see.

“You’re seeing something that cannot be captured, and you don’t know why it looks the way it looks, but you know it looks different,” Ellis said. “Your eye is seeing something that you don’t understand. That’s why they’re so effective.”

::

Day-Glo’s original paints were formulated in Berkeley in the 1930s, and were widely used by the American military in World War II on aircraft and in uniforms. Its pigments are up to four times brighter than traditional shades, and can be seen faster and from farther away.

In postwar America, Day-Glo quickly transitioned from the military to the counterculture, and through culture to art.

“In the mid- to late 1950s, Stella turned away from oil paints and started using mediums like acrylic, enamel, epoxy paints and also fluorescents,” said Katia Zavistovski, who curated the LACMA exhibit. “There’s still little understanding of how that fluorescent paint changes over time.”

What’s long been understood is this: The old shades of Day-Glo fade quickly. Pop artist Keith Haring was so distressed by this phenomenon that in the early 1980s he painted over a Day-Glo mural he’d finished just months earlier.

The ’60s-era chartreuse is particularly delicate, conservators say. But what makes Korbela’s quest especially urgent is a fungal infestation in “Bampur’s” canvas, one she has since identified in several other Stella works.

“We wanted to in-paint the little fungal speckles” to disguise the pattern made by the mold, Korbela said. Little did she know how difficult that would prove to be.

The first problem is that Saturn Yellow is a mix of both conventional color and fluorescent dye. Both types of pigment lose their brightness, but in different ways. While color fades, fluorescence is more correctly said to “extinguish” — its ability to transform invisible energy to visible light exhausted through prolonged exposure.

Finding a color match for each of these complex components is a critical step in the process of developing a usable paint. But it’s just the first step.

“When you want to retouch the painting, you must artificially age the pigment,” De Winter said.

Recent fluorescent pigments have a reformulated composition and don’t extinguish as quickly as the older ones, “which makes it impossible to match them with the old paint layer,” she added.

So Korbela spent months degrading samples of fluorescent paints that are currently on the market — a process she will begin anew with the dry pigments the company recently agreed to supply.

“I basically started to artificially age them,” she said, using the same bands of ultraviolet radiation that give you a sunburn.

The UV chamber in LACMA’s basement laboratory looks like a large toaster oven, and functions much like the light machines used to harden gel polish at nail salons.

The next step will be to tease the chemical mystery of Saturn Yellow from the polyvinyl alcohol primer that lies beneath it, a process so complicated the team can attempt it only with help from the wider Los Angeles art world.

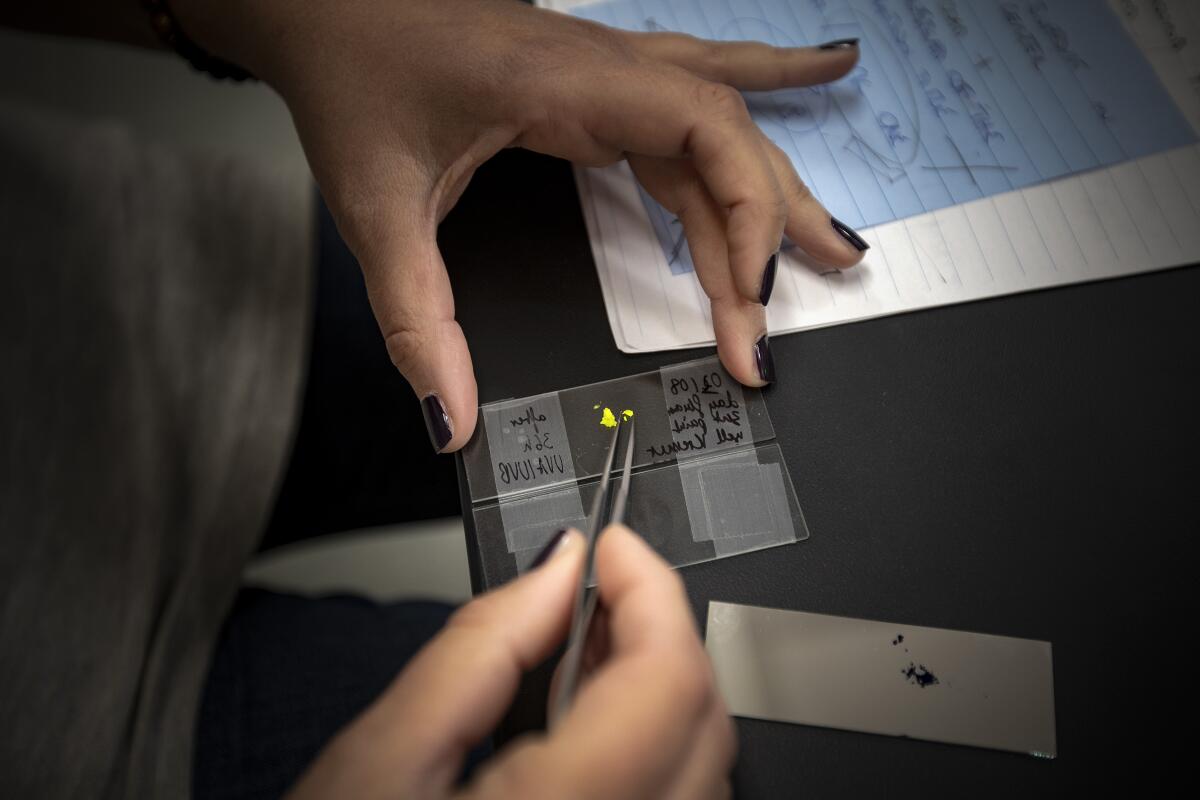

Korbela will take tiny yellow samples — dribbles collected from the edge of the “Bampur” canvas — to the lab at the Getty Conservation Institute. There they will be tested using a gas chromatic mass spectrometer — a machine that more commonly looks at chemical weapons and stardust. The next stop will be UCLA, where the samples can be analyzed using an electron microscope and other sophisticated devices to produce images at the subatomic level.

“It’s very, very rare that there is the funding for that,” Korbela said of her science. “That’s so cutting-edge it’s only happening at a couple of institutions.”

When she began chasing Saturn Yellow, Korbela still worked full time at LACMA, splitting her days between Stella’s pieces and works by Yayoi Kusama, Joan Mitchell, John Singer Sargent, Rufino Tamayo and Pablo Picasso.

Now, she runs her own conservation company, LA Art Labs, and must wait for grants and squeeze tests in on the side — a process that will probably take months.

Even after all of that, the hunt for vintage Saturn Yellow might not be over.

“We will have to do more analysis to find those perfect matches,” Korbela said. “It’s a field that’s very much still in its baby shoes.”

The team plans to apply for a National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which seeks projects that “address critical needs of the museum field.” But once they crack “Bampur’s” chemical genome, “we will have a lock-and-key principle solution for thousands of paintings,” the conservator said.

Still, actually applying it to Stella’s painting presents another challenge.

The perfect mixture, if it can be achieved, would then have to be applied to the painting with a brush made from just one or two hairs.

“If it’s too dense a layer, [the paint particles] will cast shadows on each other, and appear darker,” Korbela said.

All of which raises the question: Why labor for years to preserve an effect that is fundamentally unpleasant? Couldn’t viewers still appreciate “Bampur” if it didn’t hurt when they looked?

“Absolutely not,” said De Winter, the Day-Glo scholar. “When you cancel out the Day-Glo of the paintings you would lose the self-referential quality, the often-disturbing eye-catching effect,” and other elements the artist considered integral to his work.

Ellis was even more pointed.

“There’s many works of art done in Day-Glo hanging in our museums that no longer glow,” the expert said. “They’re still great works of art, but they lose their pow factor. If it loses that ability to hurt your eyes, it’s no longer effective.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.