The California Assembly’s keeper of rules and rituals calls it a career

SACRAMENTO — Tucked away under a small desk at the front of the California Assembly chamber is a book of parliamentary procedure. Dozens of paperclips and bookmarks peek out from its edges, a quick reference system for any question that might arise in the course of a day’s legislative session.

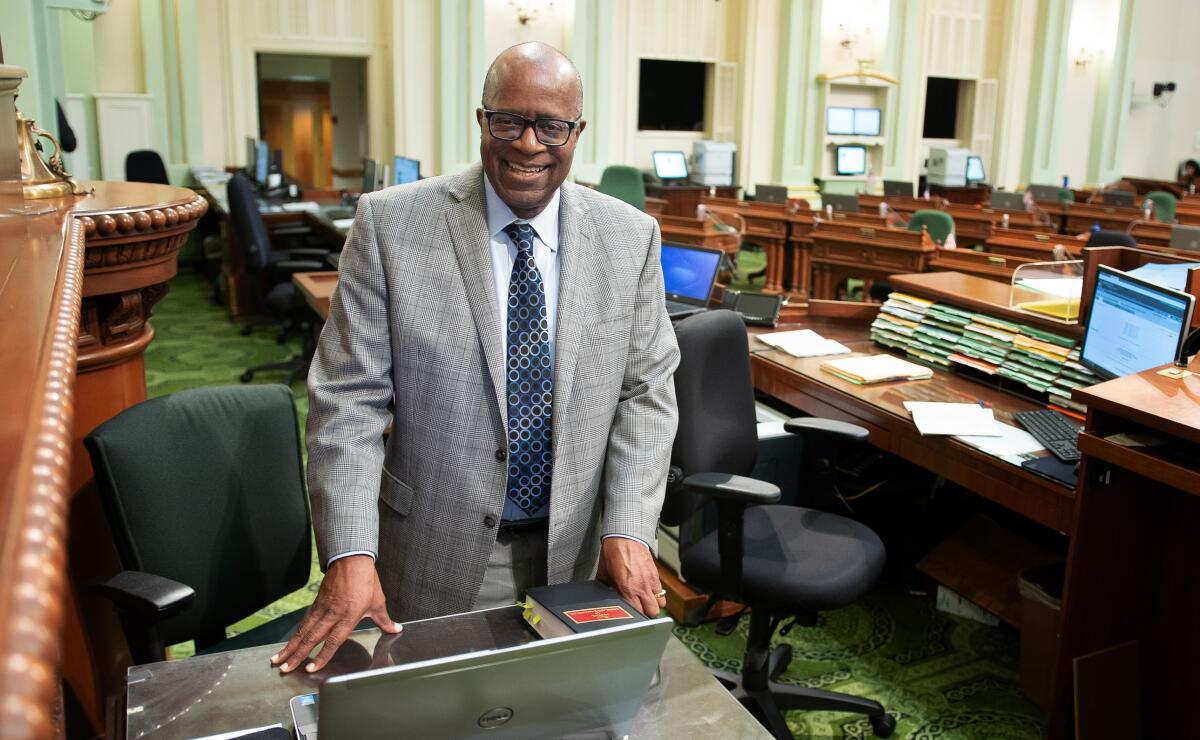

But the man who meticulously arranged the bookmarks, Chief Clerk E. Dotson Wilson, rarely needs it. After 27 years and thousands of proceedings, he has mastered the arcane rules that govern the deliberations and debate of the Assembly.

The distinction is not just the result of repetition, but part of an ethos where the explanation is just as important as the answer.

“I think you’re more effective when you’re not fumbling through books when you give members a response,” Wilson said. “You just want the elected officials to do a good job.”

No one has ever served more consecutive years as chief clerk than Wilson, who had more than a decade of legislative staff experience when tapped for the post in 1992. The 64-year-old parliamentarian will retire after the Legislature adjourns for the year on Friday, having perfected the art of impartiality in an era of hyper-partisan California politics.

“He makes us so much better,” said Assemblyman Kevin Mullin (D-South San Francisco), who leads floor sessions as Assembly speaker pro tempore. “Dotson is an institution within the institution.”

Wilson oversees a staff of 30 people, tasked with keeping track of some 3,000 pieces of legislation every two-year session and as many as a quarter-million votes cast by each Assembly member.

But as chief clerk, he does much more. Wilson is legislative historian, political referee and confidant for the 80 members of the Assembly. Advice is offered in quick whispers on the Assembly floor or private meetings in his office adjacent to the historic chamber.

And he’s an equal opportunity strategist. Wilson freely gives advice on how the rules of the house can be used to advance a lawmaker’s agenda. Sometimes, he offers guidance to opposing sides of a debate. All times, he keeps the information to himself.

“My role is to make the process as equitable and balanced as possible,” Wilson said. “I’m going to give each one of them the best information so they do what they need to do.”

That he would be so widely trusted to do the right thing wasn’t clear to some lawmakers at the beginning. Wilson joined the staff of then-Assembly Speaker Willie Brown out of law school in 1979, and was his top aide when the powerful Democrat nominated him to be chief clerk. No Republican members voted for him to hold the job, many assuming he would be under the thumb of Brown.

Wilson, the first African American to hold the job of chief clerk, set out to change people’s minds from the beginning.

“Within three months of taking the job, I went and met with every single member,” he said. “Some of the members who voted against me, they were grilling me, asking me questions. And I was OK with that.”

When the Assembly voted on Wilson’s nomination for a full two-year session the following December, the decision was unanimous. It has remained so ever since.

But an early moment in his career threatened to upend his efforts at staying out of the political fray — one of the most closely watched events in the history of the California Legislature, in which Wilson played a decisive role.

The national surge of Republican victories in the 1994 midterm elections carried GOP candidates for the Assembly into winning a single-seat majority in the lower house for the first time in a quarter-century. It would mean the removal of Brown as speaker once new members cast their votes in the ceremonial first floor session that December. But Republicans were outmaneuvered by Brown, who persuaded one Republican legislator to back him as speaker, extending his tenure. That left the Assembly in a 40-40 partisan split.

Democrats insisted Richard Mountjoy, a Republican assemblyman who had won in a special state Senate election that November, shouldn’t be allowed to cast a vote in the Assembly for speaker if he was going to resign his seat in the house days later.

They demanded a ruling from Wilson, who concluded the rules weren’t clear. He would have to either back Brown, his former mentor, or defy him.

“I had to make the ruling that anyone looking at it objectively would have made,” he said. “Would they really want me to make a ruling to kick another member out of this body, who had been elected by his constituents?”

Wilson refused to reject the Republican’s credentials. A subsequent vote for speaker ended in a tie. Brown was able to work behind the scenes to keep partial control of the Assembly the following winter and spring, while Republicans mounted recall elections against those who had defected. But Brown’s days as speaker were over.

Wilson took the stress of the situation hard, having himself checked out at a nearby hospital after the dramatic showdown.

“But I came back and did my job,” he said.

“That was a challenging moment,” said former Assembly Speaker Curt Pringle, the Republican who ultimately led the house in the aftermath of the 1994 elections, in a ceremony honoring Wilson last month. “What we did was we saw the integrity and commitment of the man.”

Few, if any, have questioned Wilson’s parliamentary accuracy in the years that followed. On Wednesday, during a tense Assembly debate over high-profile legislation to limit the use of independent contractors in California, Wilson rose from his chair as Assemblyman James Gallagher (R-Nicolaus) demanded to amend the bill.

Wilson reminded Assemblywoman Rebecca Bauer-Kahan (D-Orinda), the assistant speaker pro tempore, that an Assembly bill can’t be amended when it returns from the Senate for a final vote of concurrence. The veteran chief could be heard quietly explaining the procedure to Bauer-Kahan, who was elected last year.

Gallagher’s effort to challenge the ruling was rejected on a party-line vote. Assembly members on both sides then politely returned to their work.

Politics was not Wilson’s aspiration, even though a close family friend was Byron Rumford — a legendary state lawmaker who championed housing rights for black Californians in the ’50s and ’60s. The Wilson family had first-hand experience with the overt racism of the era’s real estate practices, finding it impossible to buy the home they wanted from a white property owner.

“So they had a Caucasian friend they went to and they got her to purchase the house,” Wilson said of his parents. That friend then signed over the deed to his family.

Wilson’s political awakening came in high school, after his local school board refused to give a track coaching job to Tommie Smith, the 1968 Olympic gold medal winner who raised a gloved fist in the air during the games’ medal ceremony.

“The school board, under pressure from parents, rescinded that offer,” he said. “If I have to think of anything that sparked my interest in politics, it was that.”

Wilson’s clerkship has spanned three distinct eras in the history of the Legislature: the period before the arrival of term limits in 1990, the dramatic change those restrictive rules made on the process of governing and the era that began when voters loosened the limits in 2012, balancing the need for competitive elections with experienced legislating.

The first iteration of term limits, he said, were troubling.

“I never saw more staff and lobbyists belittle members than during that time,” Wilson said. “The minute that someone who’s not elected believes that they’re bigger than a member who’s elected, that undermines the democratic process.”

Wilson used the arrival of term limits to help champion intensive training sessions for new legislators, who were quickly arriving and departing from their jobs. His efforts “resulted in the common good,” said state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys), who was Assembly speaker from 2000 to 2002.

A respect for rules and precedent has endeared Wilson to two generations of legislators. In a ceremony last month attended by current and former Assembly members, Assemblyman Mike Gipson (D-Carson) recounted how Wilson admonished him on his first day on the job over his choice of footwear: Gipson had chosen red sneakers to go with his suit.

“Dotson came to me and said, ‘Mr. Gipson, that is not appropriate for this floor,’” he said to laughter during the ceremony. “I took that admonishment because you cared. You value this institution ... and I honor that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.