Activists reunite to remember campaign against Prop. 187, California’s anti-illegal immigrant initiative

- Share via

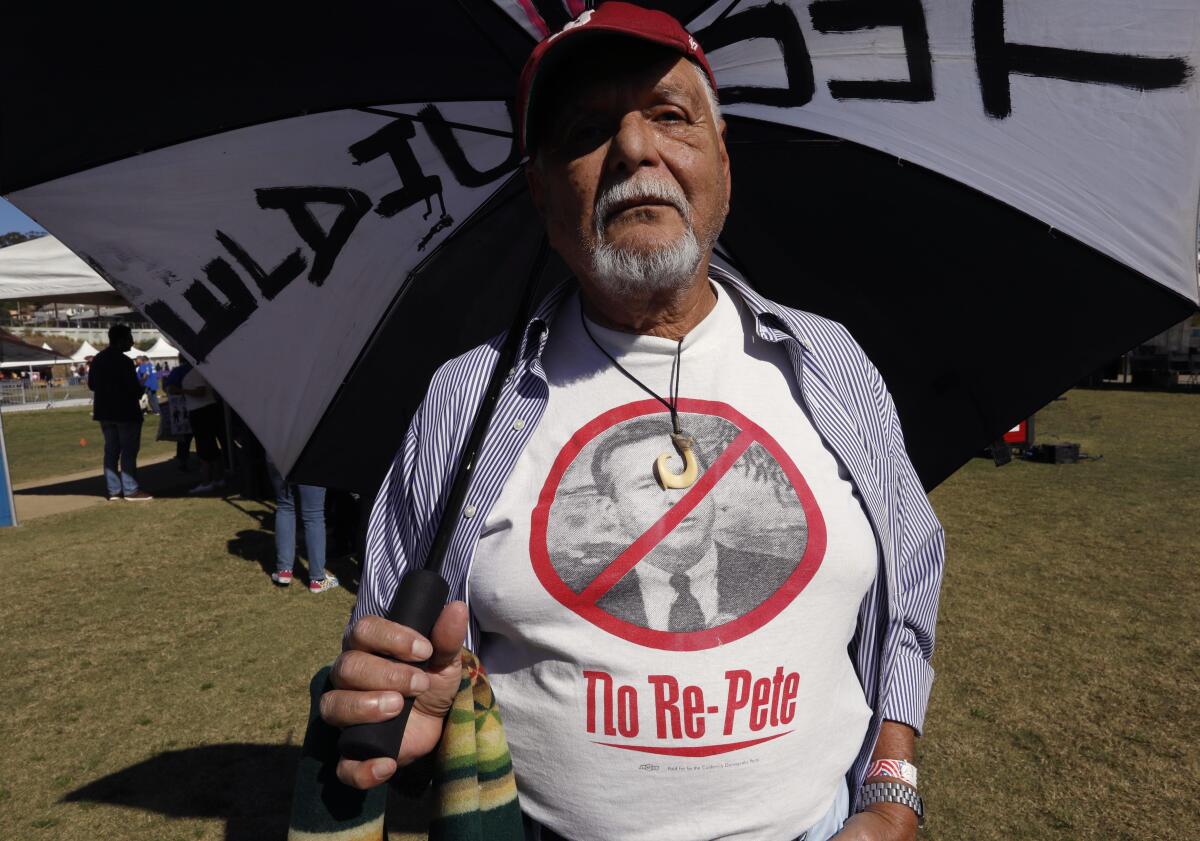

Eagle Rock attorney Don Justin Jones walked around Los Angeles State Historical Park on Saturday morning wearing a T-shirt with a crossed-out photo of former California Gov. Pete Wilson and an umbrella that stated “Chale Trump” (“No Way Trump”).

“I’m here to remember what we started,” he said, as people streamed into a tent-ringed field to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the campaign against Proposition 187. The 1994 California ballot initiative sought to deny illegal immigrants social services but instead set off a political earthquake that helped to turn California deep blue.

The measure’s backers, Jones said, suffered from “a delusion to think it was a revolution. Now, it’s an evolution.”

We are California: 25 Years Beyond 187, the coalition behind the rally, expected far more than the several hundred revelers who showed up Saturday. But the event nevertheless energized attendees, nearly all who said they were there because the United States is now going through the same xenophobia that California weathered a quarter-century ago.

Host Gustavo Arellano looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

“[Donald] Trump is worse than Pete Wilson,” said 26-year-old Vicky Ramos of Lynwood, who was too young to remember Proposition 187 when it happened but learned about it at Cal State Los Angeles. “So we gotta show people that, like Californians beat back 187’s racism, we can do the same in 2020.”

“This is about 187, but not that it happened 25 years ago. It’s today,” said Maria Elena Durazo, who was a labor organizer in 1994 and is now a Democratic state senator from Los Angeles. “We got to be just as organized now as we were then because of Trump, if not more.”

Indeed, the We Are California event was like a civic-engagement Coachella festival.

Just past the entrance, a sign in English and Spanish hanging on a fence described the anti-Proposition 187 movement as “crushing a discriminatory system that would deny us justice and equality.” It introduced a photo timeline compiled by the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor that showed activists at L.A.-area protests over the last 25 years fighting against the initiative and deportations, and for higher wages and amnesty.

In the main field, artists spray-painted on-the-spot murals, including one of the United Farm Workers flag and another one of monarch butterfly wings with the legend “Migration Is Beautiful.”

Education and health nonprofits as well as community colleges pitched their causes at tables. Volunteers with clipboards walked around and urged people to vote, participate in the 2020 census or sign a petition to change Proposition 13, California’s landmark tax-reform law that has long been a Moby Dick for progressives.

The student marches were the culmination of a month of anti-Proposition 187 teach-ins, debates, letter-writing campaigns and some of the largest protests California had seen since the Vietnam War.

Everyone was so engaged in politics that a stellar musical lineup that included Latin jazz legend Pete Escovedo and R&B singer Aloe Blacc came off as almost an afterthought.

Instead, rallygoers cheered on a parade of political dignitaries, who spoke between acts to share their stories from 25 years ago and urged everyone to participate in the 2020 elections and beyond.

“Even though it was a very dark time [in 1994],” said Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Los Angeles), “real good came out of it.”

“California is leading the resistance,” said Thomas Saenz, president of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund. His nonprofit filed a lawsuit that eventually led to Proposition 187 being declared unconstitutional by a federal court in 1997. “We have an opportunity to take that work that began 25 years ago and replicate it and take it around the country.”

“187 is a cancer that spread across the country,” said Angelica Salas of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, which helped to organize protests against the initiative. “But in California, sí se pudo [beating 187 was possible].”

The Saturday pachanga was the latest Proposition 187 event for We Are California, a coalition of politicians, professors, Univision, the Los Angeles Community College District and others who came together this year to commemorate the proposition’s anniversary. They also plan community forums, an art exhibit at the Fairplex in the spring, an educational curriculum for high schools and a one-hour documentary that will debut on KCET-TV Channel 28 next year but was previewed at the rally.

“If we’re celebrating anything, it’s the progress in California after 187,” said Secretary of State Alex Padilla, one of the We Are California committee members. He pointed out how in 1994, only 1.4 million Latinos in the state were registered to vote; now, it’s over 5 million. “All the progress that has made California a stronger state, you can tie it back to 187.”

A look back at the events surrounding the 1994 proposition.

The real party, though, was next to the stage, which served as a homecoming of sorts for Latino political power from three generations. Leaning against a fence to get what little shade there was, they greeted one another with hugs and fist-bumps.

Former L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina and state Sen. Richard Polanco, who used their offices in 1994 to decry Proposition 187, caught up with their peers. Former Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez and former state Senate Pro Tem President Kevin de Leon, who as 20-somethings helped to organize an Oct. 16, 1994, march on L.A. City Hall that drew over 70,000 people, held court with fans. Paying their respect to the veteranos were California Latino Legislative Caucus members Wendy Carrillo and Miguel Santiago.

When not catching up, the politicos gossiped. They teased about how much some of the former electeds actually did to fight Proposition 187 back in the day, traded encounters with Wilson and even commented on one another’s fashion. “Even when Antonio is wearing jeans,” said De Leon, as former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa strode around, “he looks formal.”

Nearby, Alejandra Ramirez of Wilmington sold Day of the Dead-style skulls painted with logos of NFL teams. She was in elementary school in 1994, and recalled that, while her sisters walked out of Banning High School to protest Proposition 187, her parents were “scared to be deported, even though they’re U.S. citizens.”

It was important for her to sell her goods at the rally, Ramirez said, “to let everyone know not to be scared like they were back then. Get informed. Don’t be scared.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.