Unsheltered, Part 1: In the home of cozy affluence, Orange County tries to solve homelessness

Editor’s note: This is the first story in a series examining homelessness in Orange County, including the cities of Costa Mesa, Fountain Valley, Huntington Beach, Laguna Beach and Newport Beach.

On a dreary morning about a year ago, almost 4,000 people were living with no roof over their heads in Orange County.

They instead found refuge wherever they could — huddled for warmth amid roadside shrubs in the Westside Costa Mesa neighborhood, camped under Newport Beach’s Balboa Pier, squeezed into the backseat of a van parked in Huntington Beach.

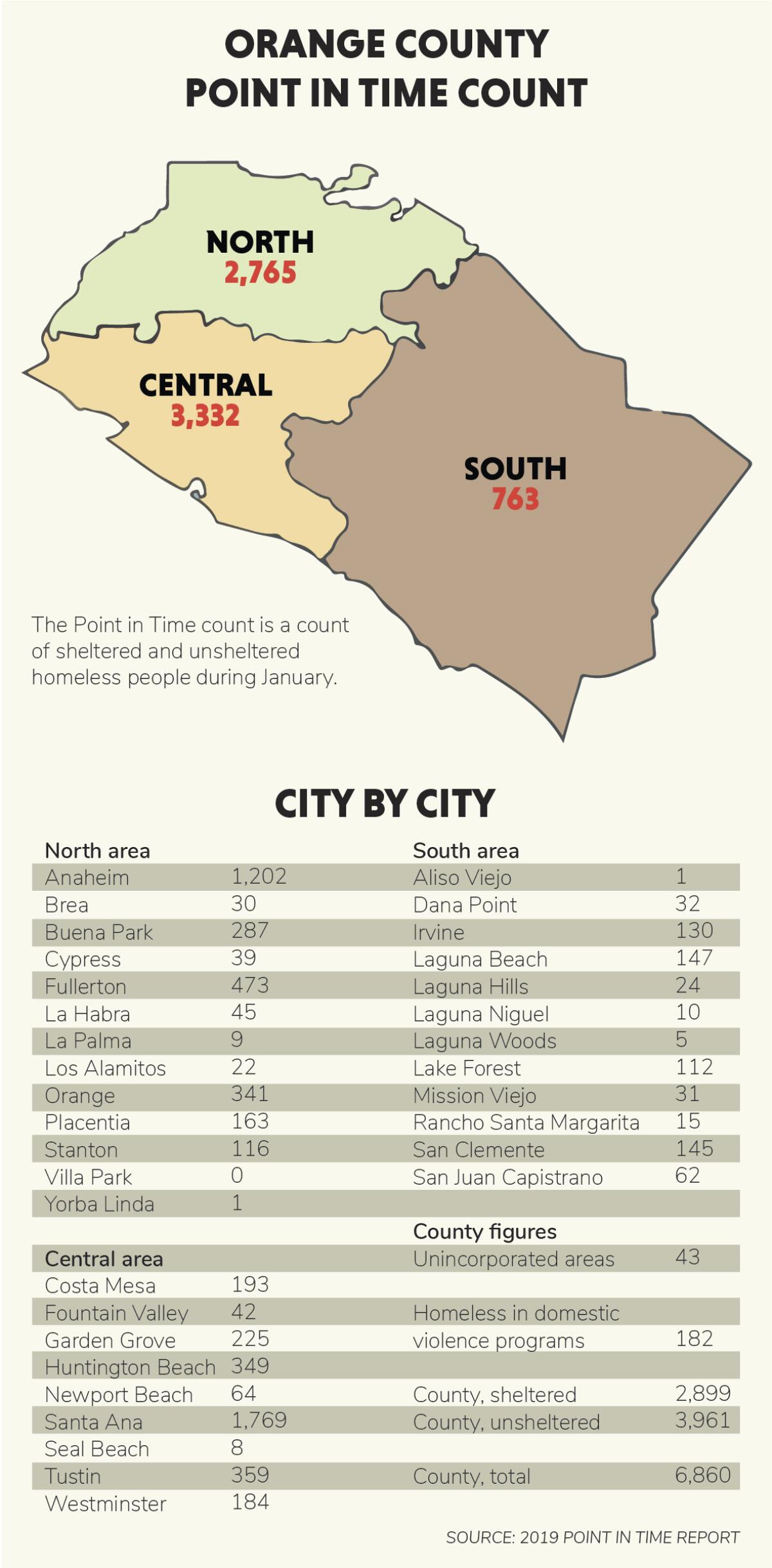

They are the homeless people of Orange County — a group that, when you include those staying in shelters or other transient living situations, numbered 6,860 in January 2019.

The latest comprehensive census of Orange County’s homeless population found nearly 7,000 people living in shelters or on the streets countywide — a significant uptick from the last such count in 2017, according to results released Wednesday.

From the outside looking in, the sprawling tent cities, like the one that mushroomed along the Santa Ana River trail in Anaheim — a stone’s throw from the Honda Center and Angel Stadium — appear to clash with the common characterization of Orange County as an archetype of sun-soaked, cozy affluence.

How, many wonder, has it come to this?

Relying on hundreds of pages of documents and dozens of interviews with local leaders, advocates, experts, public safety officials and homeless people, the Daily Pilot is taking a comprehensive look at homelessness in Orange County in hopes of answering several questions:

How did we get here? What might potential solutions look like? And what role should cities play in addressing the problem?

“There’s no one reason for homelessness, and there’s no one solution.”

— John Begin, homelessness initiative director for Trellis

There isn’t a simple answer to any of these questions. It will take bold, cooperative efforts to address homelessness in Orange County, officials, advocates and experts who spoke with the Daily Pilot said. Finding a solution will take leaders willing to see those efforts through, they agreed, even in the face of potentially fierce opposition.

“There’s no one reason for homelessness,” said John Begin, homelessness initiative director for Trellis, a Costa Mesa faith-based consortium that seeks to address significant local issues. “And there’s no one solution.”

The history

“County urged to give more assistance to the homeless.”

It’s a headline that wouldn’t look out of place today. But the article appeared in the Los Angeles Times on Aug. 2, 1985. So why is homelessness seemingly grabbing public attention now like never before?

There are several reasons, experts and advocates say. First is the sheer magnitude of the problem. Recent surveys show significant increases in the number of people living on the streets.

The “point in time” count — a federally required census of the homeless population — recorded 4,792 such individuals throughout Orange County in January 2017, including 2,584 who were unsheltered, meaning they were staying in a place where people normally wouldn’t sleep, such as on the street, in a park or in a vehicle.

Both of those numbers increased sharply in the most recent count, which recorded 6,860 homeless people, 3,961 of them unsheltered. The remaining 2,899 homeless people were “sheltered,” meaning they had a temporary roof over their heads, such as a bed in an emergency shelter or in a transitional housing program.

Most cities and counties in California reported increases in their homeless populations, but Orange County’s was among the highest. Of the state’s 15 largest continuums of care — the local planning agencies that coordinate homeless services within specific areas — the county had the fourth-largest proportional increase in its homeless population from 2017 to 2019.

But it isn’t just the size of Orange County’s homeless population that has changed. It is also where those people are. Historically, the county’s homeless people seemingly have lived on the fringes of public consciousness — not necessarily out of sight but largely out of mind. That’s no longer the case.

Homeless people have been in downtown Santa Ana for decades, “but the majority of the population didn’t see it unless they went to the courthouse or had to go get a document at the Civic Center. … It was kind of like, ‘Oh, that’s that problem in Santa Ana,’” said Helen Cameron, community outreach director for Jamboree Housing Corp., an Irvine-based developer of affordable and supportive housing.

“So when it became visible in other areas of the community and it began to be seen in parks … people felt violated,” she said. “They couldn’t use their own parks. They weren’t feeling safe.”

The 2019 homeless count reflects this dispersion. Of Orange County’s 34 cities, 16 had a homeless population of at least 100 — up from 12 two years before.

Homeless people numbered 1,769 in Santa Ana and 1,202 in Anaheim. Smaller cities such as Aliso Viejo and Yorba Linda had only one, and Villa Park had none. The count found 349 homeless people in Huntington Beach, 193 in Costa Mesa, 147 in Laguna Beach, 42 in Fountain Valley and 64 in Newport Beach.

In each case, the numbers were higher than in the 2017 count, and every city except Fountain Valley saw at least a 56% increase in its documented homeless population.

The riverbed

The increase in the number of homeless people probably came as no surprise to those who saw the scene along the Santa Ana River trail.

When officials, citing public safety and sanitation concerns, moved to clear the sprawling encampment, a handful of people living there sued the county as well as the cities of Costa Mesa, Anaheim and Orange.

The plaintiffs alleged that the cities, by enforcing local laws against camping, trespassing and loitering, had effectively criminalized homelessness and forced them to seek refuge in the riverbed. In moving to clear the camp, the plaintiffs claimed, the county was effectively pushing homeless people back into those communities without a plan to shelter them.

The case eventually triggered a seismic shift in Orange County’s homelessness landscape. The man doing most of the shaking was U.S. District Judge David Carter, who presided over the lawsuit.

From the beginning, Carter took a hands-on approach, making multiple trips to the riverbed and documenting the conditions. During conferences on the case, he repeatedly pushed city and county officials to add transitional and emergency beds. He eventually set a target of having enough beds to serve 60% of the 2,584 unsheltered people tallied during the 2017 point in time count.

Those efforts received a major boost in September 2018, when the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Martin vs. the City of Boise that it is unconstitutional to prosecute homeless people for sleeping on public property when they don’t have access to shelter.

The court found that “as long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors on public property on the false premise [that] they had a choice in the matter.”

It didn’t take long for that ruling to reverberate locally. Costa Mesa and Huntington Beach have cited it as part of their rationale for taking steps to develop a homeless shelters. Newport Beach also is considering opening a shelter.

The U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month put to rest any chance that the Boise ruling would be overturned, which would have given cities other options. It declined to hear a challenge to the case, letting the 9th Circuit decision stand.

“You’re going to see a lot more shelters go up in Orange County,” said Costa Mesa Mayor Pro Tem John Stephens. “I think ... within a year, there will be shelters complying with the city of Boise case in probably half the cities in Orange County. That’s just my guess.”

Some advocates, however, say new shelters — although welcome — are merely a Band-Aid.

“The response is not, ‘Oh, let’s find out how to have permanent solutions for homelessness through housing,’” said Julia Devanthery, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “The response has been, ‘How can we, as quickly as possible, make as many temporary shelters for people to sleep in so we can go back to criminalizing people who are not in those shelters?’”

Portrait of homelessness

Who are the people living on the streets?

A June 2017 study by Jamboree Housing Corp., UC Irvine and the Orange County United Way, titled “Homelessness in Orange County: The Costs to Our Community,” concluded that “the vast majority of Orange County’s homeless, whether male or female,” had lived in the county for at least a decade.

Information from the last point-in-time count paints a similar picture.

Of 2,146 unsheltered individuals who responded to informational surveys during the count, almost 52% said they were attending or had attended schools in Orange County or had family there. About 72% reported they were currently working or had previously worked in the county.

Almost three-quarters said their last permanent address was in Orange County.

Those findings don’t jibe with the public perception that most homeless people are outsiders drawn to California for its agreeable weather or what they might see as its more permissive policies.

A man who goes by the name “Ghost” maintained a campsite under a structure at the public bus station in Newport Beach — at least before homeless people were cleared from the depot in September.

When interviewed in July, he said he had been there for two years, pushed to sleeping in the open after a tough divorce and the last recession led him to lose his home in Costa Mesa. He said he was trapped by not being able to get a job without an address and vice versa.

In the United Way/UCI/Jamboree study, 40% of the respondents said their homelessness was fueled at least in part by their inability to secure or keep a job with sustainable wages, and 36% said they’d had difficulty finding or retaining affordable housing. Twenty-eight percent cited family-related issues such as domestic violence, the end of a relationship or the death of a relative.

Addiction and mental health issues also play a role in homelessness. Of the 252 respondents in the study, 22% said alcohol or drug use was a major contributor, while 17% cited mental health issues, and 7% pointed to a release from jail or prison.

With the nation in the grip of a deadly opioid crisis, some people have traveled to Costa Mesa and Huntington Beach to seek treatment for their addiction. Dawn Price, executive director of Friendship Shelter in Laguna Beach, said her organization had regularly worked to help people “who get sent here for rehab and then went into sober living and, for some reason, that fell apart and now they’re on the street.”

Still, the findings in the United Way/UCI/Jamboree study, “shift the focus of attention from the often-repeated stereotypical causes of homelessness, namely mental illness and substance abuse, to the gap between the availability of affordable housing and work that pays a wage sufficient to enable the economically marginal to access that housing.”

“Most people tend to imagine the kind of worst-case scenario that everybody is homeless because they’ve been released from jail or prison, they have a mental health diagnosis, they’re an addict and an alcoholic and they came from New York,” said Becks Heyhoe, director of United to End Homelessness for Orange County United Way. “We sort of make it this kind of homogeneous group.”

Tenuous economic and social circumstances aren’t unique to the Golden State, but they can be particularly pronounced in California, especially when it comes to affordable housing.

“While many factors have a role in driving California’s high housing costs, the most important is the significant shortage of housing, particularly within coastal communities,” according to a February report from the nonpartisan state legislative analyst’s office. “Today, an average California home costs 2.5 times the national average. California’s average monthly rent is about 50% higher than the rest of the country.”

Reason for optimism?

Though the homelessness issue is immense in its scale and complexity, advocates and experts say there’s light at the end of the tunnel.

In Heyhoe’s mind, a key to any discussion of how to end homelessness needs to include the question: How do we change the dialogue from despair to hope?

“We can end homelessness,” she said. “This is Orange County, California. We have the resources, the intellect. We have everything we need to end homelessness here.”

Coming in Part 2: What’s being done to address homelessness?

Money, Pinho and Davis write for Times Community News, and Vega writes for the Los Angeles Times. Times Community News staff writers Lilly Nguyen and Julia Sclafani contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.