Unsheltered, Part 3: Can Orange County cities find the political will to fix homelessness?

Editor’s note: This is the third story in a series examining homelessness in Orange County, including the cities of Costa Mesa, Fountain Valley, Huntington Beach, Laguna Beach and Newport Beach.

When it comes to the distribution of homeless services, Orange County is like a patchwork quilt.

Some cities have relatively robust resources. Others have very few. And no city has declared itself to be in charge.

“There’s no single entity that [is] sort of acknowledged as the one that’s going to take the reins and the leadership in a regional problem like this,” said Dawn Price, executive director of Friendship Shelter in Laguna Beach. “In L.A., it’s going to be [the] Los Angeles mayor and City Council…. O.C. is sitting here with a fairly large population and no central city. It’s a unique set of sort of governmental circumstances or jurisdictional circumstances that … makes it hard for people to accept responsibility or say, ‘I’ll do my part.’”

This disconnect, which extends to county and state officials, has historically presented one of the most significant challenges to addressing the growing crisis of homelessness — so much so that an Orange County grand jury report in May 2018 blamed “finger-pointing and lack of trust” between the county and cities for failures to address the regional nature of the problem.

But as tent encampments continue to pop up, local leaders are increasingly getting on the same page and acknowledging the need for more cooperation among cities, the county and the state.

The challenge now is summoning the political will, often over the objections of residents, to move ahead with solutions to homelessness. An elected official’s political fortunes could be determined by one controversial vote — and when it comes to homelessness, controversy is rarely in short supply.

Resistance from residents

Public sentiment has always played a key role in shaping cities’ responses to homelessness, advocates say. As cities across the county consider opening new homeless shelters, residents have ramped up their efforts to keep such facilities out of their proverbial backyards.

“The NIMBYs want everybody to just leave out of their neighborhoods, but they have to go somewhere,” said Bill Nelson, executive director of Fresh Beginnings Ministries, a Costa Mesa-based homeless services provider. “Somebody needs to ask at one point, ‘Whose backyard is it going to be? Where are we going to put them?’”

Residents worry that shelters will attract homeless people and that those people will ruin their neighborhoods by loitering, littering, drinking alcohol, using drugs, committing crimes and creating a general nuisance wherever they congregate. The result, they argue, will be neighborhoods that are less safe and homes that are worth less as the quality of life declines.

Meetings to discuss potential homeless shelters have, at times, morphed into heated affairs.

During a City Council meeting in April, Huntington Beach resident Doug Hein asserted — without evidence, which indicates otherwise — that a proliferation of sober-living homes and addiction-treatment facilities has lured many people to Orange County, where they eventually become homeless.

“The NIMBYs want everybody to just leave out of their neighborhoods, but they have to go somewhere. Somebody needs to ask at one point, ‘Whose backyard is it going to be? Where are we going to put them?’”

— Bill Nelson, executive director of Fresh Beginnings Ministries

“We have patients from the entire 50 states ending up here,” he said. “Our weather attracts people from many other states. So, I seriously doubt that the majority of people living on our streets are Huntington Beach residents. They’re people from other states and so, to me, it’s unfair that we have to bear … the financial burden and the burdens of housing this.”

Residents had fiercely opposed a decision by the Huntington Beach City Council to buy a building to use as a shelter. They complained that the site-selection process had been opaque and needlessly rushed. The city is now looking for another location after a group of residents, property owners and businesses sued, arguing that the first site could be used only for industrial purposes.

In Newport Beach, residents are upset over at least one possible site for a homeless shelter — the city public works yard on Superior Avenue.

“I don’t want to have to look 360 degrees every time I go for a walk or take my dog for a stroll in my own neighborhood,” homeowner Ryan Janis wrote to the city in September. “If this is added on Superior, it will increase the flow of transient monsters in my neighborhood, which is not a place anyone will ever want to raise a family or buy property.”

Some assert that being homeless is a choice.

“I am all for helping people that want to help themselves, but a lot of the homeless, if you go out there and talk to them, they don’t…. They’re happy,” Huntington Beach resident Katrina Tengan insisted in April. “They’ve got things pretty good. Do you know how much money they can make by just begging on the street? I’ll tell you, it’s more money than I can make. And yet we’re enabling this.”

Others question why cities are trying to house homeless people at all — even in Laguna Beach, which was well ahead of neighboring cities in opening a shelter, the Alternative Sleeping Location.

“I think we’re sheltering more people than we should be sheltering,” Councilman Peter Blake said, “and I would like to see those numbers reduced.”

Homeless people say they are aware of how they’re perceived. “It’s almost to a point where people are giving you resources, but they almost think they’re enabling you,” said Josh Webster, 42, a homeless resident of Laguna Beach. “But at the same time, it’s like you need those resources just to survive.”

Such claims about “enabling” Orange County’s homeless population are largely untrue. For example, a 2017 study commissioned by the United Way, UC Irvine and Jamboree Housing Corp. found “the vast majority” of homeless people are U.S. citizens and long-term Orange County residents.

Becks Heyhoe, director of the United to End Homelessness initiative for Orange County United Way, said these myths might have taken root because it’s more comfortable for the public to view homeless people as separate or different from broader society.

“When we do that, we are able to distance ourselves from them, because if we turn somebody into the other, especially … when we kind of assign blame to them — that it’s their fault that they are this way — it’s very easy for them to remain the other, and then we don’t need to engage.”

Dispelling these myths is key to changing the public’s resistance to developing resources and building shelters for homeless people, advocates say, making the role of local elected leaders even more vital.

“The political will of city councils can change outcomes,” said Helen Cameron, community outreach director for developer Jamboree Housing. “I think city councils need to show their bravery and realize that they can make a decision that can end homelessness.”

Some former and current elected officials say showing courage can carry a cost beyond losing votes.

Laguna Beach, for example, was well ahead of other Orange County cities in opening a shelter, but the American Civil Liberties Union still sued the city in 2015, accusing it of trying to push out homeless people with disabilities.

“All the example that we set was, ‘Don’t be stupid like Laguna Beach and create a shelter and then destroy your downtown, destroy Main Beach and then find yourselves being sued to the tune of millions of dollars … because of all you’ve done,’” Blake said.

Economics of homelessness

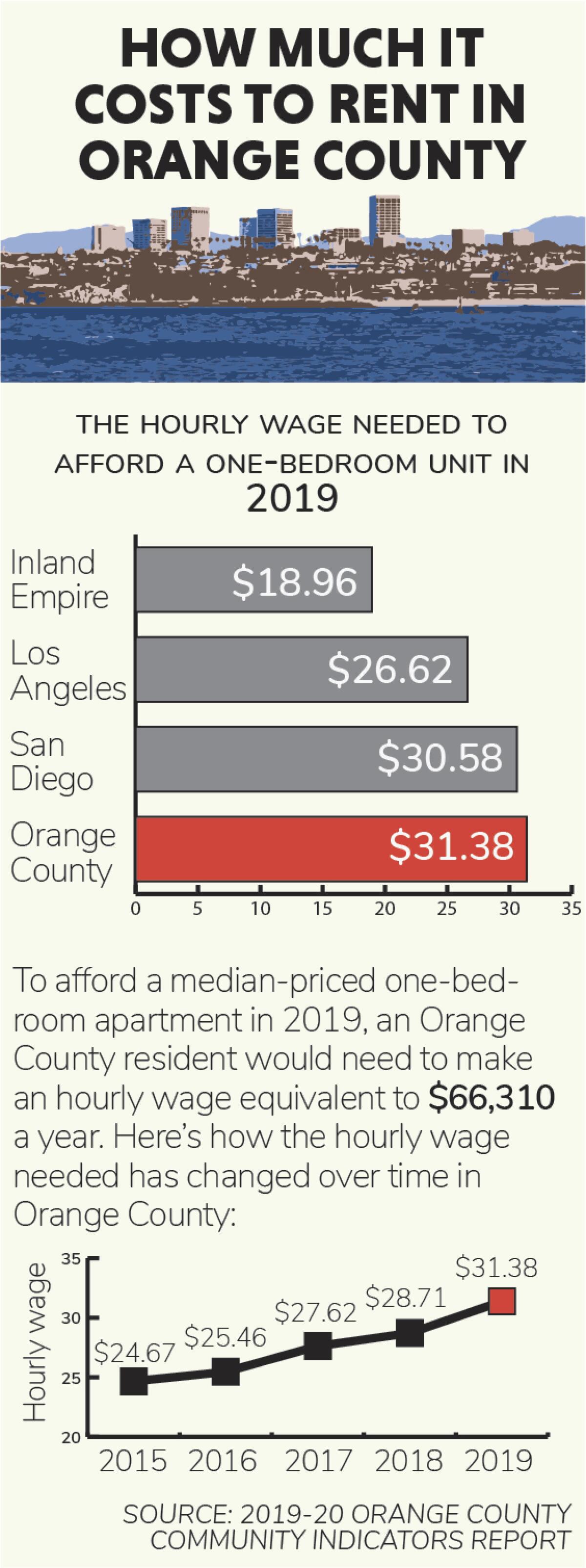

In addition to public resistance, the high price of housing is a significant hurdle to addressing homelessness.

“In our community, that’s as much based on our location as it is construction and development costs,” said Barbara Delgleize, a Huntington Beach councilwoman and real estate broker. “We also don’t have enough units at various income levels across the region … nor do we have enough shelter beds or crisis stabilization unit beds or supportive housing units.”

Advocates say shelter beds are not enough, though.

“I think we need a lot more exits from shelters so the shelter beds can turn over,” said Price, of Friendship Shelter in Laguna Beach.

Cities need to plan for what’s next, she said, and a big part of that is getting elected officials and their constituents on board with developing more affordable housing for low-income people.

“I would like to see more cities really championing housing developments in their communities, affordable for working-class poor as well as affordable for people who are homeless,” Price said.

Advocates are particularly excited about the recent creation of the Orange County Housing Finance Trust, a joint authority between the county and cities to secure and allocate funding for affordable and supportive housing projects.

Such entities are likely to be key in realizing the ultimate solution to homelessness, which is getting more people housed permanently. That will, in turn, alleviate some of the effects of the crisis on businesses and neighborhoods.

“They loiter. They carry around a lot of junk. They’re unsightly. They stink,” said David Snow, a UC Irvine professor who was an author of the 2017 homelessness study. “All of those things disappear when people have housing.”

Though much remains to be done, some elected officials have expressed optimism that their cities — and the county as a whole — are well on their way.

“Local governments have already developed partnerships in Orange County to reduce homelessness, and more partnerships are being discussed on a regular basis,” said Huntington Beach City Councilwoman Kim Carr. “If there is the political will, the financial incentive and the compassion among our residents and community leaders to solve the problem, it can be done. I don’t think there will ever be an end to homelessness in America, but I feel Orange County is on the right track and, in time, we will be the model for the rest of the nation.”

Money, Pinho and Davis write for Times Community News, and Vega for the Los Angeles Times. Times Community News staff writers Lilly Nguyen and Julia Sclafani contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.