Hospitals bracing for a wave of coronavirus patients

- Share via

The new coronavirus threatens to overwhelm California hospitals in the coming weeks unless the unprecedented social-distancing measures imposed across the state slow its rapid spread.

State projections show that the coronavirus will likely require anywhere from 4,000 to 20,000 additional hospital beds — a disturbingly imprecise estimate caused in part by the lack of testing, which has made it difficult for officials to know exactly how many people have the virus.

Based on conditions in other countries hit by the pandemic and models of what could happen in California, a rapid rise in infections expected in the next two weeks would quickly fill the existing hospital space.

A Los Angeles Times data analysis found that California has 7,200 intensive-care beds across more than 365 hospitals. In total, the state has about 72,000 beds. The Times data analysis shows roughly one intensive-care bed for every 5,500 people in California.

Experts said that capacity could easily be reached soon if the virus’ spread continues unabated.

“You can’t argue with numbers,” said Dr. Robert Winters, an infectious-disease specialist in Santa Monica. “It’s a potential brewing time bomb.”

About half of California’s total intensive-care beds — 3,700 — are in the five-county area around Los Angeles, according to data from 2018, the most recent available. Intensive-care beds allow for a higher level of treatment than regular beds, a level of care serious COVID-19 patients have needed as the illness forces them onto ventilators and attacks organs.

County-USC Medical Center in Boyle Heights had the most licensed ICU beds in the state: about 130. Those beds were occupied about 58% of the time in 2018, according to the data.

In the nine-county Bay Area, where the state’s worst outbreak is happening, there are roughly 1,400 ICU beds for a population of 7.6 million people, and they are typically occupied more than half the time with routine emergency patients, records show.

Tuesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom met with hospital leaders and medical professionals to plan for the coming influx of COVID-19 patients but offered only broad strokes of how the state would respond.

“We had a very candid and very somber, if not sobering, conversation,” Newsom said at a press briefing after the meeting. “None of it surprised any of us.”

Newsom’s estimates of existing state capacity differed from those found by The Times, with Newsom estimating that there are currently 460 hospitals with about 75,000 available beds. Those numbers appear to include about 100 facilities without ICU capabilities, some used for purposes such as rehabilitation or addiction treatment.

Newsom declined to give projected estimates for how many ICU beds might be needed in coming days.

“I could give you a total number but it would be meaningless because of conditions on the ground,” Newsom said, pointing out that needs will vary by region.

Newsom said the goal of surge planning will be to move as many noncritical patients out of hospitals as possible to preserve those facilities for critical care, and create a flexible response that can address outbreaks across the state.

Patients who require less-intensive interventions may be moved to assisted living or long-term care facilities, and those with the least medical needs may find themselves in hotels and motels the state is currently purchasing, Newsom said.

He added that the state was also in the process of leasing and bringing online two hospitals, one in Northern California and one in Southern California, to meet expected needs. Tuesday, in a measure passed with unprecedented speed, the state legslature approved $1.1 billion in emergency funding in part to increase hospital capacity and make those acquisitions.

Still, California Hospital Association CEO Carmela Coyle acknowledged at the press briefing that “our capacity will be stretched.”

Newsom said he spoke to President Trump on Tuesday to formally request federal aid to set up mobile hospitals as well, a conversation he said was well received. Trump has previously asked state governors to work on their own solutions, telling them, “we will be backing you, but try getting [supplies] yourselves.” But Tuesday, Trump said the Army Corp of Engineers would be “ready, willing and able” to assist with emergency facilities, though that roll out has not yet happened.

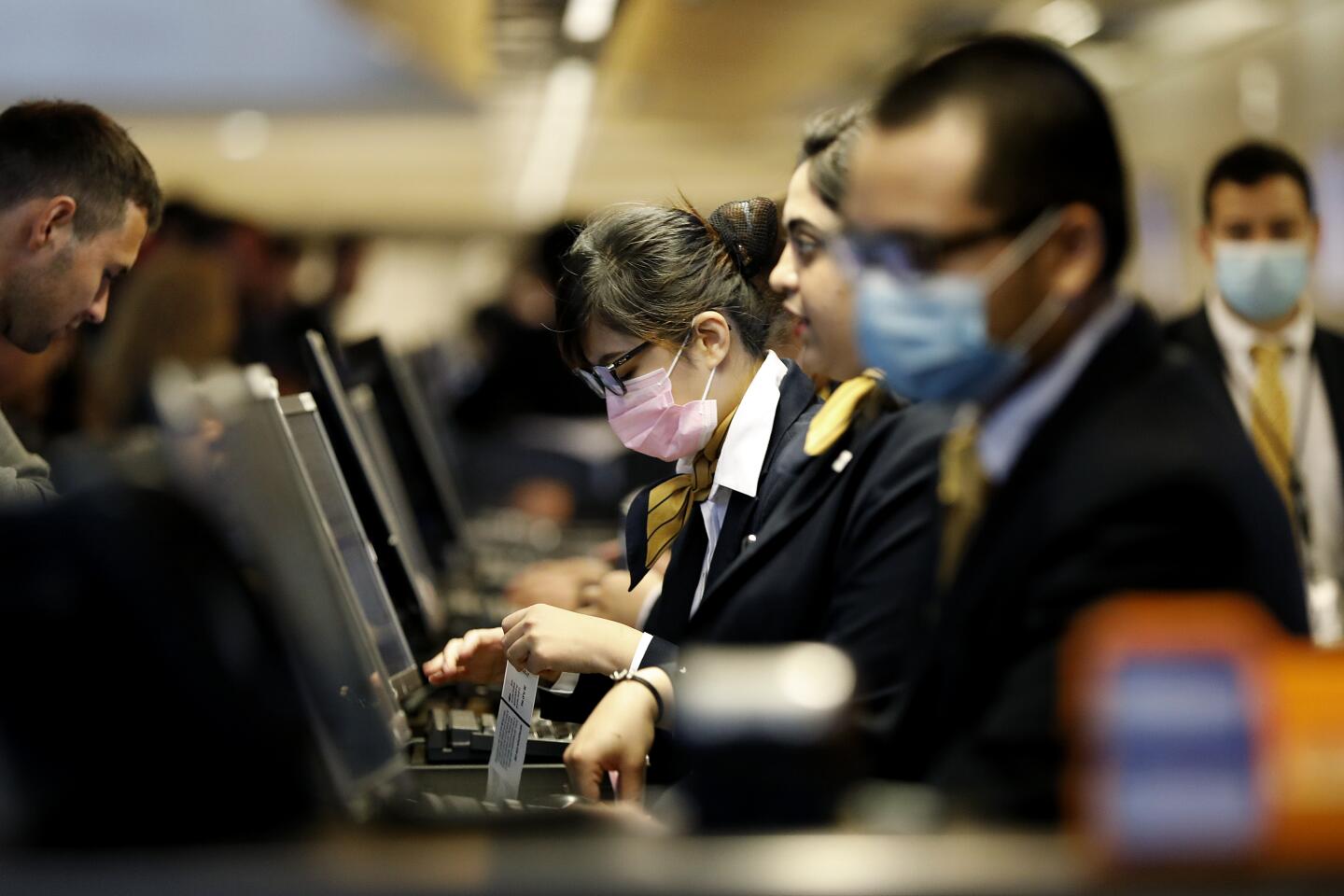

Despite the assurance of hospital administrators and state officials, healthcare workers and others are sounding alarms about readiness. A leading trade union, National Nurses United, on Monday blasted hospital administrators and federal authorities for not being prepared.

In a statement, the group’s executive director, Bonnie Castillo, said hospitals are “drastically short” in providing protective gear for nurses and other medical workers. That, she said, leaves them exposed to becoming infected themselves and exposing patients and their own families.

“Our healthcare capacity is far short of what we need to respond to this national emergency,” said Castillo, a registered nurse.

Richard Riggs, chief medical officer and senior vice president for medical affairs at Cedars-Sinai, said there’s a clear recognition at his organization that the full impact of the disease is unknown, as is the extent to which his facilities and staff will be able to cope with the strain.

“If we are short, what do we do? How do we triage patients to have the most opportunity to survive?” he said. “We’re planning with all the tools we have in our arsenal.”

Dave Pine, San Mateo County Supervisor, said Tuesday he’s “scared as to whether we can prevent an Italy-like situation despite our best efforts.”

He said, “Ideally, we should have done this two weeks ago.”

Riggs said in Beverly Hills and Marina del Rey Cedars-Sinai facilities, Monday was the last day for elective surgeries, allowing his staff to free up space for COVID-19 patients. The number of intensive-care beds capable of dealing with serious respiratory patients has expanded substantially in recent days, to nearly 100, at the Beverly Hills location. His teams are preparing to repurpose rooms, deploy triage tents, even offer drive-through testing for the disease.

David Simon, a spokesman with the California Hospital Association, said many of its members across the state were also postponing non-emergency procedures. He said COVID-19 would likely require many of them to offer care via video conference or phone, and to upgrade regular rooms into emergency ones, to make room for an onslaught of expected patients in the coming weeks.

But, said Otto Yang, an infectious disease expert at UCLA, the hard truth remains that “we don’t know how many cases we are going to see in the next days or weeks.”

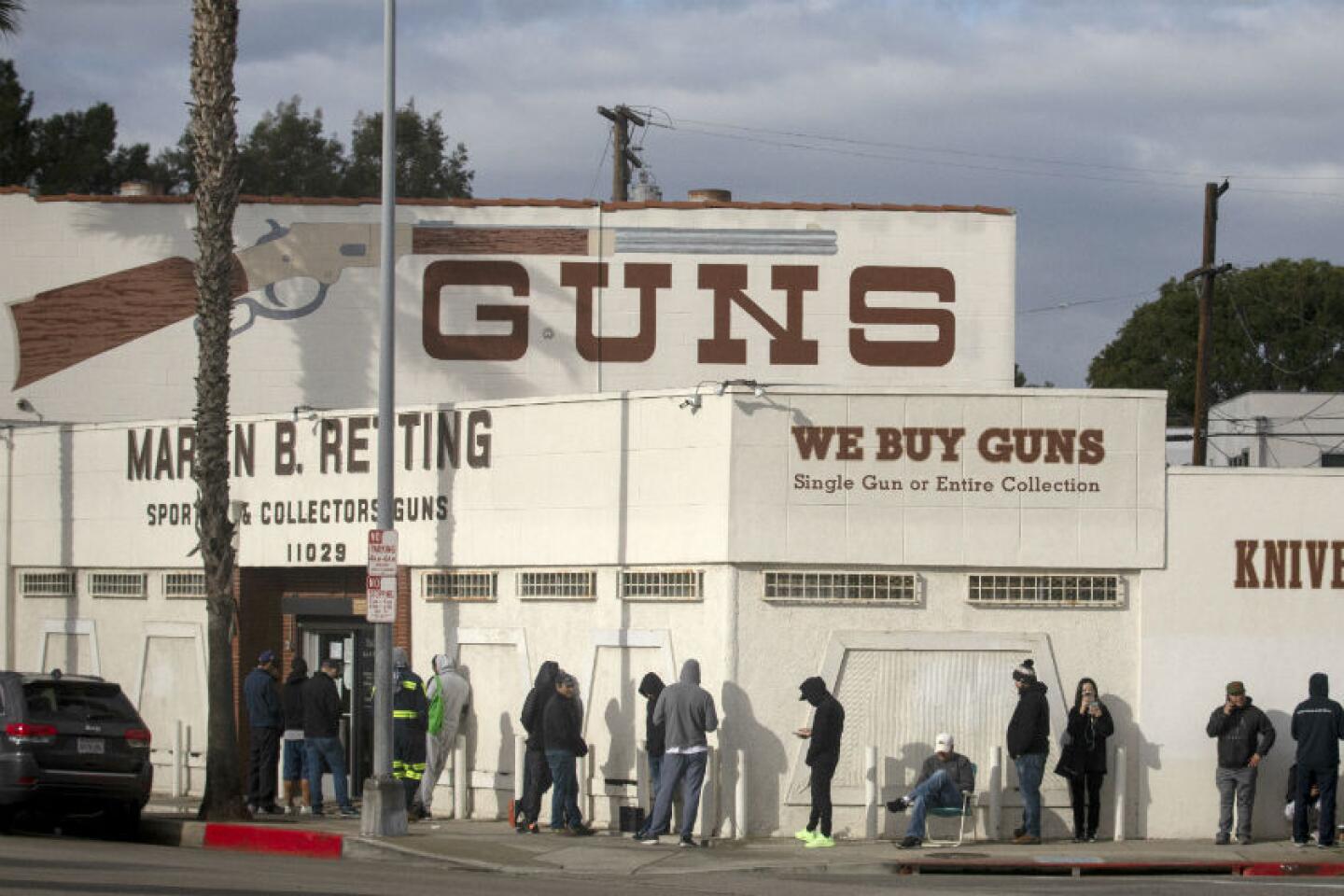

Yang and other experts said the expected surge is best viewed as the result of the failure to test for the virus in the early days of its outbreak in the U.S., leaving many undetected cases that will soon pop into official counts as they become serious enough for treatment.

They warn that testing is still not widely available, and the number of reported positive cases will likely remain artificially low for weeks as more labs come online.

Yang cautions that a surge in serious cases shouldn’t be viewed as a failure of mitigation strategies or an indicator the virus can’t be controlled in coming months.

But for now, officials are faced with battling an enemy that is invisible because of that testing misstep — forcing worst case scenarios to become default positions.

Officials are hoping the strict mitigation strategies currently keeping people inside their homes will curtail infections, giving medical systems a chance to catch up after the initial surge and blunting the wave of COVID-19 cases.

But Yang and others warn that with the lack of testing data, there is ultimately no way to know what will happen, or whether large numbers of cases will continue to enter hospitals after the first wave.

“What is not clear is how bad this is going to be,” said Yang.

Times staff writer Susanne Rust contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.