The Enneagram is having a moment. You can thank millennials

- Share via

Emily Rickard was at a casual dinner party in Riverside three years ago when a friend, a professor, mentioned a word that would change her life.

Enneagram.

The professor had recently learned about the personality test and wondered if anyone had experience with it. Rickard was immediately intrigued. And perplexed.

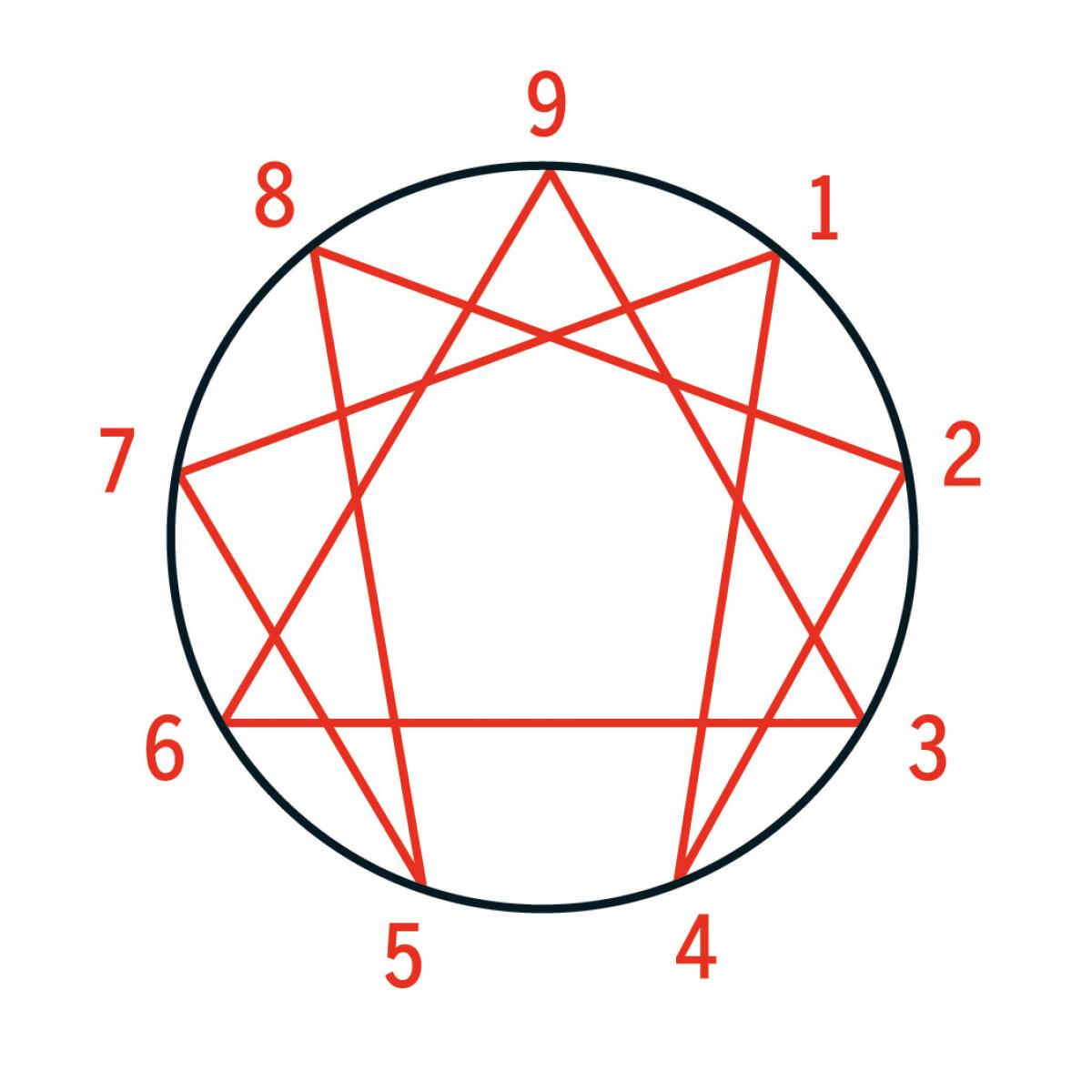

She has a master’s in psychology and a longtime fascination with personality inventories (think: Myers-Briggs), so she couldn’t believe that there was a system she hadn’t heard of. Back at home, she researched the Enneagram (pronounced ANY-uh-gram) model and how it breaks people into nine archetypes designated by a number, and sometimes a one-word nickname (“The Peacemaker,” “The Enthusiast,” “The Challenger,” “The Investigator”).

The 37-year-old, who lives in Moreno Valley with her three boys, whom she home-schools, and her husband, a teacher who also helps pastor a church in Riverside, quickly pinned herself as a Nine — “The Peacemaker.” (Figuring out your type often starts with an online assessment that asks you to agree or disagree with generic statements, such as “I want people to tell me the truth, not spare my feelings.”)

As she read about the Nine’s key motivations — avoiding conflict and maintaining harmony, sometimes by putting others’ interests ahead of your own — she flashed back to her childhood and how, when her parents argued, she felt like the world might end. She thought, too, about the times her husband insisted that she pick a dinner spot, and she simply shrugged, elevating his cravings above hers.

Which Enneagram type are you? Here is a rundown of the nine personality types.

The epiphany brought her to tears, feeling as if her authentic self had, at last, been fully recognized. Soon she enrolled in a 12-week, online course offered by a company called Your Enneagram Coach, that, for about $1,000, promised an overview of the nine types, as well as help setting up a freelance gig as a life coach teaching from the Enneagram perspective. Now, she runs a coaching service called NextGen Enneagram, offering a $350 package that includes a 30-minute, pinpoint-your-type interview and six longer one-on-one meetings.

“Once you get the Enneagram bug,” she says, “it’s kind of contagious.”

Actually, quite contagious.

Sixteen years of Google searches show that the number of people looking up “Enneagram” hovered at the same level until 2017, when it spiked drastically, topping out last summer. In August, for the first time in its history, the Narrative Enneagram, a nonprofit that teaches students how to use the model, sold almost every space at six workshops in Menlo Park, according to founding president Terry Saracino, who has taught the Enneagram for more than 30 years.

“The Enneagram is exploding,” she said. “Expanding like crazy.”

The boom, which until the pandemic broke out involved people gathering for Enneagram parties and workshops, is part of the same contemporary phenomenon that some observers connect to the resurgence of astrology — in turbulent times, some people find comfort in the rituals of their religion or other, less traditional, belief systems. When the world feels especially chaotic, said Fran Grace, a professor of religious studies at the University of Redlands, we crave tools that help us change the one thing we can control — ourselves.

“It’s the inner path,” Grace said. “How can I be a place of peace?”

Like many other Enneagram converts, Rickard is something of a personal-development junkie. She saw a marriage and family therapist during grad school, knows her Myers-Briggs type by heart and recently met with a woman who coaches people using neurolinguistic programming, a self-help therapy that sometimes uses hypnotic techniques.

And while she recognizes that some of the Enneagram’s allure is its trendiness — “It’s popular right now, so go with it, right?” she says with a laugh — she finds the model less stagnant and more growth-oriented than other personality systems and believes that it will stand the test of time.

::

Mention the word Enneagram in a group — or DISC or Myers-Briggs or any of the hundreds of tests that distill personalities into a color or a number or an animal — and you’ll almost always spot at least one person rolling their eyes, convinced its all well-packaged nonsense. Personality tests, skeptics have long argued, are nothing more than pseudoscience that create a buyer-beware world of little regulation where anyone can call themselves an expert.

The Enneagram itself has ancient, but murky, roots: Some adherents trace it back to a 4th century monk and the same underlying concept as the seven deadly sins. Others see similarities between the Enneagram’s nine-pointed figure and a symbol used in ancient Sufism.

But the modern interpretation is credited to Bolivian-born philosopher Oscar Ichazo, and one of his students, a Berkeley-based psychiatrist, who, in the 1970s, helped popularize the Enneagram in the U.S. By 1994, the model had gained at least enough credence that Stanford Medical School’s psychiatry department co-sponsored the first International Enneagram Conference, drawing more than a thousand people to Palo Alto.

From there, the framework found pockets of popularity with self-help devotees and in Corporate America, where some companies used the tool to build rapport among employees. It also gained traction in some Christian circles, propelled, in part, by a book on the topic by an influential Franciscan priest named Richard Rohr. Then, thanks to millennials, it exploded into the mainstream in the last few years. In many ways, the tool, which isn’t tied to a specific religion, seems tailor-made for a spiritual-but-not-religious generation that grew up on BuzzFeed quizzes and branding.

‘The Enneagram helps people get to what is greater. To be really internally happy, peaceful, content.’

— Milton Stewart, podcast host for “Do It For the Gram”

Enneagram evangelists tout it as a self-discovery tool that will help you understand your strengths and limitations, spot patterns you fall into during stress and communicate more clearly. It’s not about fundamentally altering yourself or trying to morph into another type — that, they’ll remind you, is impossible anyway — but about living more consciously with the hand you’ve been dealt.

In a world saturated with self-help tools, it’s the Enneagram’s digestibility that sets it apart.

The nine archetypes are easy to distill into cute and encouraging memes, like the ones shared to half a million followers on the @enneagramandcoffee Instagram account or the GIFs of puppies and Enneagram jokes tweeted by the @Enneadog account. Companies capitalizing on the craze now claim to know the best smoothie bowl and iPhone app for each type and there are more than 20 different podcasts with “Enneagram” in their title, including one called “Do It For the Gram” hosted by Milton Stewart, a Seven (“The Enthusiast.”)

The 30-year-old, who lives in Memphis and proudly calls himself “The Enneagram Guy,” says the tool is a natural fit for him, and fellow millennials who want to move beyond discussions of success and toward a loftier goal: True happiness.

“The Enneagram helps people get to what is greater,” he said. “To be really internally happy, peaceful, content.”

Another part of the Enneagram’s appeal is that nobody owns it.

A few well-established groups, such as the Enneagram Institute and the Narrative Enneagram, host intensive workshops, some of which can cost into the thousands of dollars. (In a club exploding with newbie converts, groups that started talking about the Enneagram decades ago carry a certain cachet.)

But people can also research for free online and label themselves a guru.

“There’s no overarching body that says, ‘You can’t say you’re an Enneagram expert,’” said Micky ScottBey Jones, 42, a Nashville-area Enneagram trainer, who got certified through an extensive online program taught by the School of Conscious Living in Cincinnati.

The lack of quality control is problematic, Jones acknowledged, because someone with only a cursory understanding of the Enneagram could call themselves a trainer and start charging money. And when the tool is used without nuance, she said, discussions can devolve into deterministic stereotypes.

“Oh, you think you’re perfect?” Jones recalls her ex-husband quipping at her, knowing she was a One, sometimes nicknamed “The Perfectionist.” The opposite was true, she told him, Ones have the fiercest “inner critic” of any number.

“It’s not a party trick,” she said.

It takes serious research to understand the tool’s subtleties, Jones said, and to account for the cultural biases inherent in some of the quizzes and trainings. As with anything, she said, Enneagram teachers interpret the world through the lens of their own lives and, historically, at least in the U.S., most instructors have been white.

When Jones, who is black, first started having conversations about the Enneagram, other people told her, and she initially agreed, that she was probably an Eight (“The Challenger”). But she later realized that that was a common mistyping among black women — one she believes is rooted in stereotypes about black women as angry and strong. While she is a leader with a strong personality — traits often found in Eights — a key aspect was off: She doesn’t freely express her anger. As a One (aka “Perfectionist”), she’s prone to tamp the emotion down.

One way to weed out your true type, Enneagram experts say, is to read all nine descriptions and focus on the one that unsettles or embarrasses you. That was how Paden Hughes — the 33-year-old CEO of Gymnazo, a workout facility in San Luis Obispo — ultimately discovered her type. She initially thought she might be an Eight, but realized she was a Three (“The Achiever”) after learning that, at their lowest, Threes are prone to shape-shifting and manipulation.

“It’s the side of you that you don’t want anyone to see,“ Hughes said. But recognizing that side, she believes, spurs growth.

She implemented the Enneagram with her then 15-person staff more than a year ago and, so far, she said, the employees have liked it more than other personality-typing tools they’d tried together, including Myers-Briggs and Strengths Finder.

On a Saturday morning last fall, Hughes’ gym hosted a two-hour Enneagram workshop led by Joy Pedersen — a 41-year-old life coach and certified Enneagram instructor who has a doctorate in educational leadership.

“I want us to do introductions,” Pedersen said softly, asking each of the participants to share a fun fact about themselves, as well as their experience with the Enneagram and what they hoped to get from the workshop.

First up was a 38-year-old preschool teacher — fun fact: She’s from Fargo, N.D. — who said she knew almost nothing about the Enneagram, but that she kept seeing the word on Instagram. Then a 59-year-old commercial real estate agent — fun fact: she has anxiety from a lack of fun facts — said she struggled with understanding people and hoped to improve her communication skills.

“Oooh,” Pedersen said, smiling, “that gets me really excited.”

The next day, a different group — a crew of 18 men and women — packed into a living room in Riverside for an Enneagram party led by Rickard, the devotee who lives in Moreno Valley.

Dressed in a sparkly T-shirt and exuding the loud, stay-with-me energy of someone who spends her time home-schooling a trio of young boys, Rickard clapped three times. The crowd — her friends, her friend’s friends and a few strangers who’d learned about the event online — quieted.

“So,” Rickard said, squirming with excitement, “who has heard of the Enneagram?”

Eighteen hands popped up.

“Who is obsessed with it like me?” she asked.

When only four hands stayed raised, Rickard inched her eyebrows up and down several times, as if to say, “Challenge accepted.”

Some Christians are leery about the Enneagram because it’s not derived directly from the Bible, Rickard said, but that doesn’t bother her — or her husband, a pastor at a nondenominational Christian church. Nothing about it contradicts their beliefs, she says, or those of any of the other world religions she’s studied.

“Anything that gives you insight into how you’re made can be helpful,” she said.

As Rickard outlined the types in a PowerPoint presentation, a mother, who was bouncing her baby on her knee, asked if women with young children ever get mistyped as Twos (“The Helper”). Rickard nodded, saying women — and particularly women in religious communities — are often mistyped because selflessness is a trait they’re taught to value and therefore learn to express.

As she pointed to her PowerPoint, a stack of gold bracelets bounced around her left wrist. She winced.

“This is so jingly,” she said. “Is that annoying anyone?”

A friend in the back of the room chuckled, noticing the worry-about-everyone-else question.

“Ah,” she whispered to herself, “The Peacemaker.”

You could argue, of course, that anyone giving a public talk might fret over distracting noises. But that wasn’t what the friend saw — not now that she was a believer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.