- Share via

The plan started simply enough. As the pandemic forced schools to shutter in March, three families in a leafy corner of downtown Riverside banded together to make sure all their children kept learning.

The record-producer dad taught music classes. The court-commissioner mom gave speech lessons. There was time for art and silent reading and yoga and schoolwork assigned remotely by teachers who seemed very far away. Class began at 9 a.m., no pajamas, no excuses.

But achieving that modest goal — caring for each other’s children — became far more complicated as the virus’ toll mounted. What began as a home school dubbed the Brothbush Academy ended up as a kind of coronavirus commune, as the quarantined families came to depend on each other to stay healthy and safe.

The Bristows and the Roths live side by side in century-old houses, one Craftsman-style, one Spanish Revival. Classes are held in one home or the other, and the gate separating their yards swings wide seven days a week, a constant stream of kids and parents, dogs and food, flowing back and forth. The Furbushes live 900 feet away — walk to the corner, hang a right, and you’re there.

The families had been inseparable since long before anyone heard of COVID-19. Which is what made the March 28 meeting at the Roths’ long dining room table so painful.

After dinner, the grownups began hashing out the most difficult details of caring for seven adults and nine children ranging in age from 6 to 14 as the deadly disease spread around the globe. Hard choices normally made in the confines of a single family were suddenly being debated by a committee.

The group had to figure out how to balance its collective well-being against the needs of two of its members: Truck driver Will Furbush, the group’s only “essential” worker, whose livelihood requires him to be out in the dangerous world, and Dalina Furbush, his 14-year-old daughter from an earlier relationship, who was about to leave the safe circle to spend time with her mother.

The Bristows, Roths and Furbushes had vowed to support each other through the dark time ahead. After all, they’d had each others’ backs for years. But the choices they would make had the power to shatter the tight bond that held them together.

When Will and Dalina ventured out into an environment that could not be controlled, would the group allow them to come back home?

::

Before the commune came the school. And before the school came the schedule, Kristen Bristow’s effort to bring order to coronavirus chaos.

COLUMN ONE

COLUMN ONE

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Kristen had spent nearly two decades teaching third grade in the Riverside Unified School District. So, when school ended abruptly on Friday, March 13, she knew she had to do something to keep her family from lolling around in pajamas for weeks at a time.

Starting on March 16, the three Bristow girls had six and a half proscribed hours a day: 9 a.m. classwork; 10 a.m. physical education; 11 a.m., more classwork; noon, lunch; and on and on. The Roth kids joined in a few days later, bringing the student load to six.

Then came spring break, and with it, the big decisions.

Gov. Gavin Newsom had put the whole state on lockdown.

Dr. Cameron Kaiser, the Riverside County public health officer, had banned all gatherings of more than 10 people.

And Gabe Roth asked Kristen and her husband Dave if the Furbushes — Will, who is married to Gabe’s sister Samra, and the three Furbush children — could join the collective home school. All of a sudden, there would be 16 people in the quarantine commune, a half-dozen over the limit.

Kristen’s sister-in-law sent her a text: “I guess your whole ‘school thing’ is out the door.”

A few weeks later, Kristen recounted her hopeful response: “But families are not subjected to that.”

She was sitting on the Roths’ porch, trying to keep her face mask in place while explaining the intricacies of Brothbush Academy. On the other side of a big front window, Gabe was playing a sequence of notes on a guitar and having the little kids echo it back to him on piano.

“We just decided, who’s to say we’re not family?” Kristen continued. “Not that we wanted to break any rules. But it was so beneficial to all of us, and we’re being so careful.”

Staying in was the order of the day. All groceries were purchased online and delivered. Food was shared. No one outside of the three families and Wayne Gordon, a visitor from Brooklyn who was stranded at the Roths’ for nearly three months, was allowed inside the homes. No grandparents. No friends.

Interviews for this article were conducted from at least six feet away, through masks or on the phone. Neither the reporter nor the photographer set foot in any of the three houses.

“We’re really trying to compensate for the luxury of being together by being extra vigilant in our contact with everybody else,” Gabe said during an interview at his roomy, brown-shingled home.

He was inside the house, the front door closed. The reporter was outside, wearing a mask.

“If there’s a way to do something with less risk or no risk, how much sacrifice is it?” he asked. “Which is why I’m talking with you on the phone.”

::

Students at Brothbush Academy have learned a few things that aren’t in the curriculum at what they call “real school.”

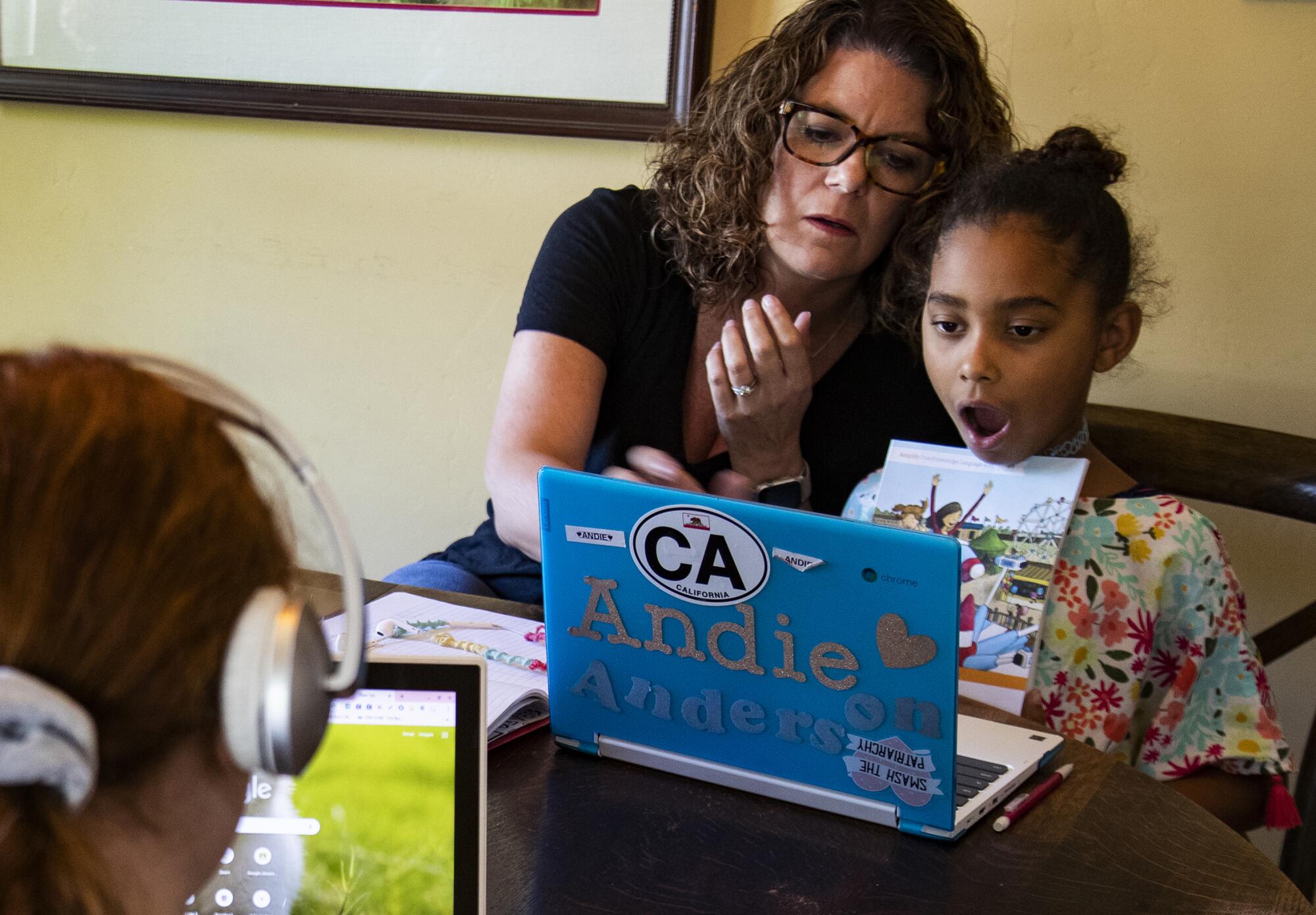

At 9 a.m. on a Thursday in April, Andie Bristow was already at the kitchen table, her head peeking up over her sky-blue laptop. Her hair was tied up in two little buns and she was munching on cantaloupe, clutching her baby doll, ready for school.

At 6 years old, Andie is the youngest Brothbush student, and the start of her school day went something like this:

Andie: What’s today, Mommy?

Kristen: Today’s Thursday, sweetie.

Andie: Mommy, do I have my [Google] meet now?

Kristen: No, it’s at 9:30. You have half an hour.

Andie: What’s today, Mommy?

The Brothbush parents are not fans of distance learning for the youngest students — children such as Sylvester Roth, 8, and Andie, who are still learning the basics — but twice each week, Andie clicks into a live video chat via Google Classroom with her two teachers and 20 or so fellow first-graders at Benjamin Franklin Elementary School. The group’s done video scavenger hunts and guessing games and accomplished a little math here and there.

On this morning, when the meeting time rolled around, Andie had a crackly white plastic bag in her hand and a big smile on her face. She’d picked three friends to guess what’s in her bag, and no one was making any headway.

She laughed and pulled out the mystery object, waving it in front of the webcam so the whole class could see. Ta da! “It’s a marker,” she said, triumphant.

Penelope Roth, 11, and Carmen Furbush, 10, were at the Bristows’ dining room table, heads bent over laptops. Kat Bristow, at 12 one of two middle-schoolers in the bunch, was curled up in an overstuffed chair, typing fast. Her bare feet hung over the chair’s striped arm.

The highlight of every school day starts at 1:30 p.m. Lunch, music, art and silent reading have ended, and the students gather around the Roths’ dining room table. Sometimes there is instruction, but often the students are paired up — a young child with an older one — and given a research assignment that ends in a presentation to the group.

They’ve looked into nutrition, reporting on what happens if you have too much or too little of, say, carbohydrates or protein. They’ve researched life in other countries, and what makes people tick, sharing the intricacies of culture and diet.

But on this Thursday afternoon, the group had a special assignment: Each pair of students had to assess the pros and cons of home school and “real school.”

They were unanimous on just a few things, such as the superiority of home school bathrooms and lunches. Their judgments were rendered the old-fashioned way — handwritten on paper or white board.

Allison Furbush, age 7: Something good about real school is there’s nothing good about real school, except my teachers and friends.

Rosie Roth, age 9: The good things about home school is you get to wake up at 8 a.m. instead of 6. And you get to swim in the pool, which is awesome. The bad things are: We. Turn. In. To. Ro. Bots. Stair. Ring. At. Our. Com. Pute. Er. Screens. Too. Much.

Staying safe comes at a cost.

::

The Brothbush Academy doesn’t operate in a bubble. For all the precautions the families have been taking, two factors are out of its control: a teenager who needs to see her mother and an essential worker who must be on the road.

Even without the coronavirus, Will Furbush wages a constant battle against germs when he travels in his Freightliner Cascadia, 76 feet long when a trailer’s attached. He wears gloves to pump diesel and work on the truck. He keeps a 32-ounce bottle of hand sanitizer nearby and wipes down the truck’s interior with Lysol.

Long-haul trucking is a solitary life; it’s even lonelier with coronavirus restrictions. But when he is not on the road, no money comes in. Truck payments and insurance bills do not go away.

“Looking at the industry, it’s like, you don’t feel like you’re essential,” Will said. “You feel like you’re a slave. You have to go to work. If you don’t, you starve.”

When Will and his daughter Dalina left the Furbushes’ gray shingle house on April 1, they did not know when they would see it again.

Days earlier, at the family meeting in the Roths’ dining room, the adults had agreed on a plan they hoped would keep the families safe without banishing two members of their inner circle.

Will had promised to quarantine himself for 14 days at a cousin’s in Long Beach after each run. Dalina, who during normal times alternates each week between her mom’s house and her dad’s, would stay away for the month of April, at the very least.

“That to me was the hardest,” Gabe said. “Trying to make these decisions about when can you come home and when can you not come home ... and doing this communally.”

On April 8, Will was finishing a run and heading back to Southern California. He planned to be here for five days, but Long Beach and the cousin’s house hadn’t worked out, and there was no backup plan. Samra just knew that she didn’t want her husband sleeping in the truck, so close and yet so far away.

“I wanted him to come home,” she said. “Him quarantining somewhere else is stupid. I missed him.”

So she set up a conference call. Will was in the Freightliner, driving. The Brothbush Academy adults were in the Bristows’ living room. Samra had planned to connect with Will beforehand so they could figure out how best to persuade the group that he was safe enough to come home between runs.

But the strategy session never took place.

She dialed Will’s number, put her cellphone on speaker and set it on the coffee table. And Will promised yet again to stay away for 14 days after every trip.

“It all went backwards from the way I wanted it to happen,” Samra recounted. “I was in this weird position. He was going to end up in town for five days. I wanted him to just come home. That was a tense situation.”

On April 10 at 11 p.m., Will called. He said he was already in L.A. County. Samra asked him what he was going to do. He said he didn’t know. The Furbush home was filled with girls, a Brothbush sleepover.

“I said, ‘Come home’,” Samra recounted. “He said, ‘We should talk to everyone.’ ... The next morning at around 8:30, I texted everyone. ‘Will’s in L.A. He’s going to be here a few days. Is it cool if he comes home?’”

She didn’t hear back until early afternoon. By then, the kids were all at the Bristows’, or maybe the Roths’ (if it’s not one, it’s the other). And Will was already home.

“I was a wreck,” Samra said.

“No one said, ‘you’re kicked out of the band,’” Not directly, anyway. But later that weekend, she talked to Gabe.

“He said, ‘We’re all going to go to our houses for a week and regroup,’” she recounted. During that period, the families stayed in their own homes with no face-to face communication. There were no joint classes; the children could not play together; no meals were shared.

“I felt, ‘Oh, man, I screwed this all up.’”

::

A few days later, Will left again, this time for nearly a month. Classes and harmony resumed at Brothbush Academy.

On May 10, he returned to Riverside. He picked up Dalina at her mom’s house, and they headed home. The house was empty. A “Welcome Home” sign hung over the front door. Samra, Allison and Carmen were staying at the Roths’.

Will and Dalina got tested for the virus the next day. If the tests came back negative, the Furbushes would reunite. If not, the father and daughter would quarantine together for two more weeks.

Samra and the Brothbush students walked over later that day to welcome Will and Dalina home and to celebrate Carmen’s 11th birthday. The Furbushes have an old boat parked on a trailer in front of the house, and Will and Dalina had already climbed in. Everyone else stood on the sidewalk. Social distance.

“We purposely stayed in the boat to stay away from them, because otherwise there might’ve been a slip-up,” Will said from his porch swing. Dalina was seated close beside him. Their shoulders touched. They wore protective masks.

“My youngest is trying to inch closer and closer. And you could see it in her face that she really wants to just ...” Will paused, choked up. He could not finish the sentence. She really wants to just hug me. “That was really tough for me, to try to keep the strength together to not just grab my baby. That’s my baby.”

The test results for Will and Dalina had been promised in 48 to 72 hours.

They actually took a couple of days more.

For the three families — and especially for a stressed and sleepless Samra — it was the longest stretch of the whole pandemic.

The test results arrived on May 15. Negative for both.

Samra texted the next morning: “We are all back home together now.”

Times photographer Gina Ferazzi contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.